Forming Impressions of Others

When we use perception to size up other people, we form interpersonal impressions—mental pictures of who people are and how we feel about them. All aspects of the perception process shape our interpersonal impressions: the information we select as the focus of our attention, the way we organize this information, the interpretations we make based on knowledge in our schemata and our attributions, and even our uncertainty.

Given the complexity of the perception process, it’s not surprising that impressions vary widely. Some impressions come quickly into focus. We meet a person and immediately like or dislike him or her. Other impressions form slowly, over a series of encounters. Some impressions are intensely positive, others neutral, and still others negative. But regardless of their form, interpersonal impressions exert a profound impact on our communication and relationship choices. To illustrate this impact, imagine yourself in the following situation.

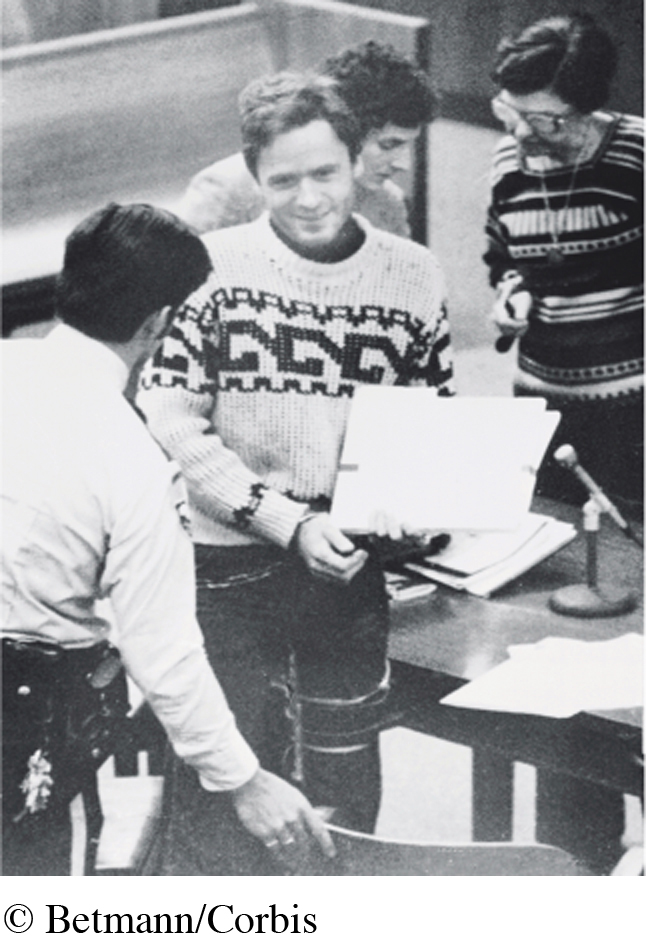

It’s summer, and you’re at a lake, hanging out with friends. As you lie on the beach, the man pictured in the photo at right approaches you. He introduces himself as “Ted” and tells you that he’s waiting for some friends who were supposed to help him load his sailboat onto his car. He is easy to talk to, is friendly, and has a nice smile. His left arm is in a sling, and he casually mentions that he injured it playing racquetball. Because his arm is hurting and his friends are missing, he asks if you would help him with his boat. You say, “Sure.” You walk with him to the parking lot, but when you get to Ted’s car, you don’t see a boat. When you ask him where his boat is, he says, “Oh! It’s at my folks’ house, just up the hill. Do you mind going with me? It’ll just take a couple of minutes.” You tell him you can’t go with him because your friends will wonder where you are. “That’s OK,” Ted says cheerily, “I should have told you it wasn’t in the parking lot. Thanks for bothering anyways.” As the two of you walk back to the beach, Ted repeats his apology and expresses gratitude for your willingness to help him. He’s polite and strikes you as sincere.

Think about your encounter with Ted, and all that you’ve perceived. What’s your impression of him? What traits besides the ones you’ve observed would you expect him to have? What do you predict would have happened if you had gone with him to his folks’ house to help load the boat? Would you want to play racquetball with him? Would he make a good friend? Does he interest you as a possible romantic partner?

The scenario you’ve read actually happened. The description is drawn from the police testimony of Janice Graham, who was approached by Ted at Lake Sammamish State Park, near Seattle, Washington, in 1974 (Michaud & Aynesworth, 1989). Graham’s decision not to accompany Ted saved her life. Two other women—Janice Ott and Denise Naslund—were not so fortunate. Each of them went with Ted, who raped and murdered them. Friendly, handsome, and polite, Ted was none other than Ted Bundy, one of the most notorious serial killers in U.S. history.

Thankfully, most of the interpersonal impressions we form don’t have life-or-death consequences. But all impressions do exert a powerful impact on how we communicate with others and whether we pursue relationships with them. For this reason, it’s important to understand how we can flexibly adapt our impressions to create more accurate and reliable conceptions of others.

CONSTRUCTING GESTALTS

One way we form impressions of others is to construct a Gestalt, a general sense of a person that’s either positive or negative. We discern a few traits and, drawing on information in our schemata, arrive at a judgment based on these traits. The result is an impression of the person as a whole rather than as the sum of individual parts (Asch, 1946). For example, suppose you strike up a conversation with the person sitting next to you at lunch. The person is funny, friendly, and attractive—characteristics associated with positive information in your schemata. You immediately construct an overall positive impression (“I like this person!”) rather than spending additional time weighing the significance of his or her separate traits.

Gestalts form rapidly. This is one reason why people consider first impressions so consequential. Gestalts require relatively little mental or communicative effort. Thus, they’re useful for encounters in which we must render quick judgments about others with only limited information—a brief interview at a job fair, for instance. Gestalts are also useful for interactions involving casual relationships (contacts with acquaintances or service providers) and contexts in which we are meeting and talking with a large number of people in a small amount of time (business conferences or parties). During such exchanges, it isn’t possible to carefully scrutinize every piece of information we perceive about others. Instead, we quickly form broad impressions and then mentally walk away from them. But this also means that Gestalts have significant shortcomings.

The Positivity Bias In 1913, author E. H. Porter published a novel titled Pollyanna, about a young child who was happy nearly all of the time. Even when faced with horrible tragedies, Pollyanna saw the positive side of things. Research on human perception suggests that some Pollyanna exists inside each of us (Matlin & Stang, 1978). Examples of Pollyanna effects include people believing pleasant events are more likely to happen than unpleasant ones, most people deeming their lives “happy” and describing themselves as “optimists,” and most people viewing themselves as “better than average” in terms of physical attractiveness and intellect (Matlin & Stang, 1978; Silvera, Krull, & Sassler, 2002).

Pollyanna effects come into play when we form Gestalts. When Gestalts are formed, they are more likely to be positive than negative, an effect known as the positivity bias. Let’s say you’re at a party for the company where you just started working. During the party, you meet six coworkers for the first time and talk with each of them for a few minutes. You form a Gestalt for each. Owing to the positivity bias, most or all of your Gestalts are likely to be positive. Although the positivity bias is helpful in initiating relationships, it can also lead us to make bad interpersonal decisions, such as when we pursue relationships with people who turn out to be unethical or even abusive.

The Negativity Effect When we create Gestalts, we don’t treat all information that we learn about people as equally important. Instead, we place emphasis on the negative information we learn about others, a pattern known as the negativity effect. Across cultures, people perceive negative information as more informative about someone’s “true” character than positive information (Kellermann, 1989). Though you may be wondering whether the negativity effect contradicts Pollyanna effects, it actually derives from them. People tend to believe that positive events, information, and personal characteristics are more commonplace than negative events, information, and characteristics. So when we learn something negative about another person, we see it as unusual. Consequently, that information becomes more salient, and we judge it as more truly representative of a person’s character than positive information (Kellermann, 1989).

self-reflection

Think of someone for whom you have a negative Gestalt. How did the negativity effect shape your impression? Now call to mind personal flaws or embarrassing events from your past. If someone learned of this information and formed a negative Gestalt of you, would his or her impression be accurate? fair?

Needless to say, the negativity effect leads us away from accurate perception. Accurate perception is rooted in carefully and critically assessing everything we learn about people, then flexibly adapting our impressions to match these data. When we weight negative information more heavily than positive, we perceive only a small part of people, aspects that may or may not represent who they are and how they normally communicate.

Halos and Horns Once we form a Gestalt about a person, it influences how we interpret that person’s subsequent communication and the attributions we make regarding that individual. For example, think about someone for whom you’ve formed a strongly positive Gestalt. Now imagine that this person discloses a dark secret: he or she lied to a lover, cheated on exams, or stole from the office. Because of your positive Gestalt, you may dismiss the significance of this behavior, telling yourself instead that the person “had no choice” or “wasn’t acting normally.” This tendency to positively interpret what someone says or does because we have a positive Gestalt of them is known as the halo effect (see Table 3.3 on p. 89).

| The Halo Effect | ||

|---|---|---|

| Impression | Behavior | Attribution |

| Person we like :) | Positive behavior | Internal |

| Person we like :) | Negative behavior | External |

| The Horn Effect | ||

| Person we dislike :( | Positive behavior | External |

| Person we dislike :( | Negative behavior | Internal |

| Note: Information in this table is adapted from Guerin (1999). | ||

The counterpart of the halo effect is the horn effect, the tendency to negatively interpret the communication and behavior of people for whom we have negative Gestalts (see Table 3.3). Call to mind someone you can’t stand. Imagine that this person discloses the same secret as the individual previously described. Although the information in both cases is the same, you would likely chalk up this individual’s unethical behavior to bad character or lack of values.

skillspractice

Algebraic Impressions

Strengthen your ability to use algebraic impressions.

When you next meet a new acquaintance, resist forming a general positive or negative Gestalt.

Instead, observe and learn everything you can about the person.

Then make a list of his or her positive and negative traits, and weigh each trait’s importance.

Form an algebraic impression based on your assessment, keeping in mind that this impression may change over time.

Across future interactions, flexibly adapt your impression as you learn new information.

CALCULATING ALGEBRAIC IMPRESSIONS

A second way we form interpersonal impressions is to develop algebraic impressions by carefully evaluating each new thing we learn about a person (Anderson, 1981). Algebraic impressions involve comparing and assessing the positive and negative things we learn about a person in order to calculate an overall impression, then modifying this impression as we learn new information. It’s similar to solving an algebraic equation, in which we add and subtract different values from each side to compute a final result.

Consider how you might form an algebraic impression of Ted Bundy from our earlier example. At the outset, his warmth, humor, and ability to chat easily with you strike you as “friendly” and “extraverted.” These traits, when added together, lead you to calculate a positive impression: friendly + extraverted = positive impression. But when you accompany Bundy to the parking lot and realize his boat isn’t there, you perceive this information as deceptive. This new information—Ted is a liar—immediately causes you to revise your computation: friendly + extraverted + potential liar = negative impression.

When we form algebraic impressions, we don’t place an equal value on every piece of information in the equation. Instead, we weight some pieces of information more heavily than others, depending on the information’s importance and its positivity or negativity. For example, your perception of potential romantic partners’ physical attractiveness, intelligence, and personal values will likely carry more weight when calculating your impression than their favorite color or breakfast cereal.

As this discussion illustrates, algebraic impressions are more flexible and accurate than Gestalts. For encounters in which we have the time and energy to ponder someone’s traits and how they add up, algebraic impressions offer us the opportunity to form refined impressions of people. We can also flexibly change them every time we receive new information about people. But since algebraic impressions require a fair amount of mental effort, they aren’t as efficient as Gestalts. In unexpected encounters or casual conversations, such mental calculations are unnecessary and may even work to our disadvantage, especially if we need to render rapid judgments and act on them.

USING STEREOTYPES

A final way we form impressions is to categorize people into social groups and then evaluate them based on information we have in our schemata related to these groups (Bodenhausen, Macrae, & Sherman, 1999). This is known as stereotyping, a term first coined by journalist Walter Lippmann (1922) to describe overly simplistic interpersonal impressions. When we stereotype others, we replace the subtle complexities that make people unique with blanket assumptions about their character and worth based solely on their social group affiliation.

We stereotype because doing so streamlines the perception process. Once we’ve categorized a person as a member of a particular group, we can apply all of the information we have about that group to form a quick impression (Bodenhausen et al., 1999). For example, suppose a friend introduces you to Conor, an Irish transfer student. Once you perceive Conor as “Irish,” beliefs that you might hold about Irish people could come to mind: they love to tell exaggerated stories (the blarney), have bad tempers, like to drink, and are passionate about soccer. Mind you, none of these assumptions may be accurate about Irish people or relevant to Conor. But if this is what you believe about the Irish, you’ll keep it in mind during your conversation with Conor and look for ways to confirm your beliefs.

As this example suggests, stereotyping frequently leads us to form flawed impressions of others. One study of workplace perception found that male supervisors who stereotyped women as “the weaker sex” perceived female employees’ work performance as deficient and gave women low job evaluations, regardless of the women’s actual job performance (Cleveland, Stockdale, & Murphy, 2000). A separate study examining college students’ perceptions of professors found a similar biasing effect for ethnic stereotypes. Euro-American students who stereotyped Hispanics as “laid-back” and “relaxed” perceived Hispanic professors who set high expectations for classroom performance as “colder” and “more unprofessional” than Euro-American professors who set identical standards (Smith & Anderson, 2005).

Stereotyping is almost impossible to avoid. Researchers have documented that categorizing people in terms of their social group affiliation is the most common way we form impressions, more common than either Gestalts or algebraic impressions (Bodenhausen et al., 1999). Why? Social group categories such as race and gender are among the first things we notice about others upon meeting them. As a consequence, we often perceive people in terms of their social group membership before any other impression is even possible (Devine, 1989). The Internet provides no escape from this tendency. Without many of the nonverbal cues and additional information that can distinguish a person as a unique individual, people communicating online are even more likely than those communicating face-to-face to form stereotypical impressions when meeting others for the first time (Spears, Postmes, Lea, & Watt, 2001).

self-reflection

Think of an instance in which you perceived someone stereotypically based on the information the person posted online (photos, profile information, tweets). How did the information affect your overall impression of him or her? your communication with the person? What stereotypes might others form of you, based on your online postings?

Most of us presume that our beliefs about groups are valid. As a consequence, we have a high degree of confidence in the legitimacy of our stereotypical impressions, despite the fact that such impressions are frequently flawed (Brewer, 1993). We also continue to believe in stereotypes even when members of a stereotyped group repeatedly behave in ways that contradict the stereotype. In fact, contradictory behavior may actually strengthen stereotypes. For example, if you think of Buddhists as quiet and contemplative and meet a talkative and funny Buddhist, you may dismiss his or her behavior as atypical and not worthy of your attention (Seta & Seta, 1993). You’ll then actively seek examples of behavior that confirm the stereotype to compensate for the uncertainty that the unexpected behavior aroused (Seta & Seta, 1993). As a result, the stereotype is reinforced.

You can overcome stereotypes by critically assessing your beliefs about various groups, especially those you dislike. Then educate yourself about these groups. Pick several groups you feel positively or negatively about. Read a variety of materials about these groups’ histories, beliefs, attitudes, values, and behaviors. Look for similarities and differences between people affiliated with these groups and yourself. Finally, when interacting with members of these groups, keep in mind that just because someone belongs to a certain group, it doesn’t necessarily mean that all of the defining characteristics of that group apply to that person. Since each of us simultaneously belongs to multiple social groups, don’t form a narrow and biased impression of someone by slotting him or her into just one group.