Feelings and Moods

FEELINGS AND MOODS

We often talk about emotions, feelings, and moods as if they are the same thing. But they’re not. Feelings are short-term emotional reactions to events that generate only limited arousal; they do not typically trigger attempts to manage their experience or expression (Berscheid, 2002). We experience dozens, if not hundreds, of feelings daily—most of them lasting only a few seconds or minutes. An attractive stranger casts you an approving smile, causing you to feel momentarily flattered. A friend texts you unexpectedly when you’re trying to study, making you feel briefly annoyed. Feelings are like small emotions. Common feelings include gratitude, concern, pleasure, relief, and resentment.

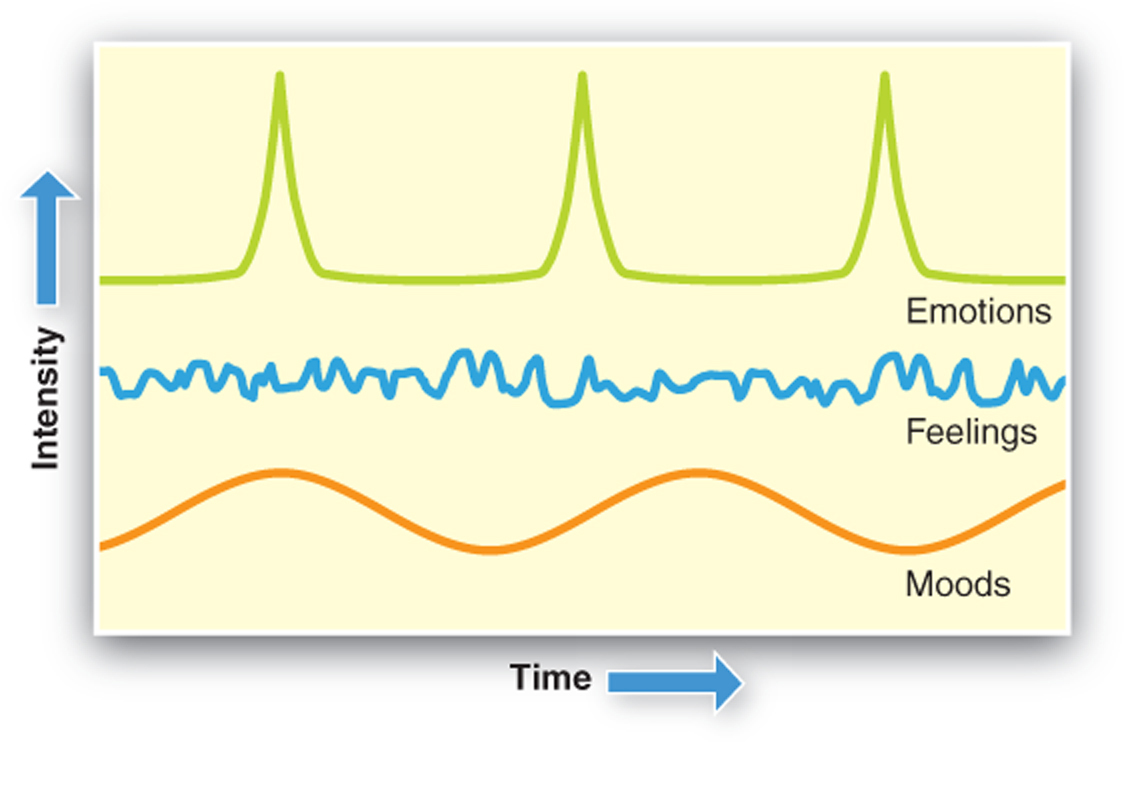

Whereas emotions occur occasionally in response to substantial events, and feelings arise frequently in response to everyday incidents, moods are low-intensity states—such as boredom, contentment, grouchiness, or serenity—that are not caused by particular events and typically last longer than feelings or emotions (Parkinson, Totterdell, Briner, & Reynolds, 1996). Positive or negative, moods are the slow-flowing emotional currents in our everyday lives. We can think of our frequent, fleeting feelings and occasional intense emotions as riding on top of these currents, as displayed in Figure 4.1.

Moods powerfully influence our perception. People who describe their moods as “good” are more likely than those in bad moods to form positive impressions of others (Forgas & Bower, 1987); are more likely than those in bad moods to perceive new acquaintances as “sociable,” “honest,” “giving,” and “creative” (Fiedler, Pampe, & Scherf, 1986); and are more likely to fall prey to the fundamental attribution error (Forgas, 1998)—attributing others’ behaviors to internal rather than external causes (see Chapter 3). Taken together, these findings suggest that people in positive moods aren’t especially good perceivers. Why? Because they tend to selectively focus only on things that seem positive and rewarding (Tamir & Robinson, 2007), and they don’t process information thoughtfully. In simple terms, when you’re happy, you tend to skim along the perceptual surface and not deeply ponder things (Hunsinger, Isbell, & Clore, 2012).

Our moods also influence our communication, including how we talk with partners in close relationships (Cunningham, 1988). People in good moods are significantly more likely to disclose relationship thoughts and concerns to close friends, family members, and romantic partners. In contrast, people in bad moods typically prefer to not communicate, instead preferring to sit and think, be left alone, and avoid social and leisure activities (Cunningham, 1988).

self-reflection

How do you behave toward others when you’re in a bad mood? What strategies do you use to better your mood? Are these practices effective in elevating your mood and improving your communication in the long run, or do they merely provide a temporary escape or distraction?

Despite the perceptual shortcomings associated with positive mood states, most people prefer positive moods because negative moods are so unpleasant (Thayer, Newman, & McClain, 1994). Unfortunately, some of the most commonly practiced strategies for improving bad moods—drinking alcohol or caffeinated beverages, taking recreational drugs, and eating—are also the least effective and may actually worsen your bad mood (Thayer et al., 1994). More effective strategies for improving bad moods are ones that involve active expenditures of energy, especially strategies that combine relaxation, stress management, mental focus and energy, and exercise. The most effective strategy of all appears to be rigorous physical exercise (Thayer et al., 1994). Sexual activity does not seem to consistently elevate mood.

TYPES OF EMOTIONS

Take a moment and look at the emotions communicated by the people in the photos below. How can you discern the emotion expressed in each picture? One way to distinguish between different types of emotions is to examine consistent patterns of facial expressions, hand gestures, and body postures that characterize specific emotions. By considering these patterns, scholars have identified six primary emotions that involve unique and consistent behavioral displays across cultures (Ekman, 1972). The six primary emotions are surprise, joy, disgust, anger, fear, and sadness.

Some situations provoke especially intense primary emotions. In such cases, we often use different words to describe the emotion, even though what we’re experiencing is simply a more intense version of the same primary emotion (Plutchik, 1980). For instance, receiving a gift from a romantic partner may cause intense joy that we think of as “ecstasy,” just as the passing of a close relative will likely trigger intense sadness that we label as “grief” (see Table 4.1).

| Primary Emotion | High-Intensity Counterpart |

|---|---|

| Surprise | Amazement |

| Joy | Ecstasy |

| Disgust | Loathing |

| Anger | Rage |

| Fear | Terror |

| Sadness | Grief |

In other situations, an event may trigger two or more primary emotions simultaneously, resulting in an experience known as blended emotions (Plutchik, 1993). For example, imagine that you borrow your romantic partner’s phone and accidentally access a series of flirtatious texts between your partner and someone else. You’ll likely experience jealousy, a blended emotion because it combines the primary emotions anger, fear, and sadness (Guerrero & Andersen, 1998): in this case, anger at your partner, fear that your relationship may be threatened, and sadness at the thought of potentially losing your partner to a rival. Other examples of blended emotions include contempt (anger and disgust), remorse (disgust and sadness), and awe (surprise and fear) (Plutchik, 1993).

While North Americans often identify six primary emotions—surprise, joy, love, anger, fear, and sadness (Shaver, Wu, & Schwartz, 1992)—some cultural variation exists. For example, in traditional Chinese culture, shame and sad love (an emotion concerning attachment to former lovers) are primary emotions. Traditional Hindu philosophy suggests nine primary emotions: sexual passion, amusement, sorrow, anger, fear, perseverance, disgust, wonder, and serenity (Shweder, 1993).

focus on CULTURE: Happiness across Cultures

Happiness across Cultures

A Chinese proverb warns, “We are never happy for a thousand days, a flower never blooms for a hundred” (Myers, 2002, p. 47). Although most of us understand that our positive emotions may be more passing than permanent, we tend to presume that greater joy lies on the other side of various cultural fences. If only we made more money, lived in a better place, or even were a different age or gender, then we would truly be happy. But the science of human happiness has torn down these fences, suggesting instead that happiness is interpersonally based.

Consider class, the most common cultural fence believed to divide the happy from the unhappy. Studies suggest that wealth actually has little effect on happiness. Across countries and cultures, happiness is unaffected by the gain of additional money once people have basic human rights, safe and secure shelter, sufficient food and water, meaningful activity with which to occupy their time, and worthwhile relationships.

What about age? The largest cross-cultural study of happiness and age ever conducted, which examined 170,000 people in 16 countries, found no difference in reported happiness and life satisfaction based on age (Myers, 2002). And gender? Differences in gender account for less than 1 percent in reported life happiness (Michalos, 1991; Wood, Rhodes, & Whelan, 1989). Men and women around the globe all report roughly similar levels of happiness. Even population density drops as a predictor of joy: people in rural areas, towns, suburbs, and big cities report similar levels of happiness (Crider, Willits, & Kanagy, 1991).

When asked, “What is necessary for your happiness?” people overwhelmingly cite satisfying close relationships with family, friends, and romantic partners at the top of their lists (Berscheid & Peplau, 2002). Faith also matters. Studies over the past 20 years in both Europe and the United States have repeatedly documented that people who are religious are more likely to report being happy and satisfied with life than those who are nonreligious (Myers, 2002). Finally, living a healthy life breeds joy. The positive effect of exercise on mood extends to broader life satisfaction: people who routinely exercise report substantially higher levels of happiness and well-being than those who don’t (Myers, 2002).

discussion questions

What are your own sources of happiness and life satisfaction?

Do you agree that interpersonal relationships, spiritual beliefs, and healthy living are the most essential ingredients for happiness?