Co-Cultures

CO-CULTURES

As societies become more culturally diverse, awareness of how various cultures, and groups of people within them, interact increases. In any society, there’s usually a group of people who have more power than others—that is, the ability to influence or control people and events. (We’ll discuss power in more detail in Chapter 9.) Having more power in a society comes from controlling major societal institutions, such as banks, businesses, the government, and legal and educational systems. According to Co-cultural Communication Theory, the people who have more power within a society determine the dominant culture, because they get to decide the prevailing views, values, and traditions of the society (Orbe, 1998). Consider the United States. Throughout its history, wealthy Euro-American men have been in power. When the United States was first founded, the only people allowed to vote were landowning males of European ancestry. Now, more than 200 years later, Euro-American men still make up the vast majority of U.S. Congress and Fortune 500 CEOs. As a consequence, what is thought of as “American culture” is tilted toward the interests, activities, and accomplishments of these men.

self-reflection

Which of your co-cultures is most important in shaping your sense of self? Which ones are less important? (For example, you may identify strongly as a Latina but not identify as strongly as a Catholic.) Why? Are there ever situations in which your different co-cultural identities clash with one another?

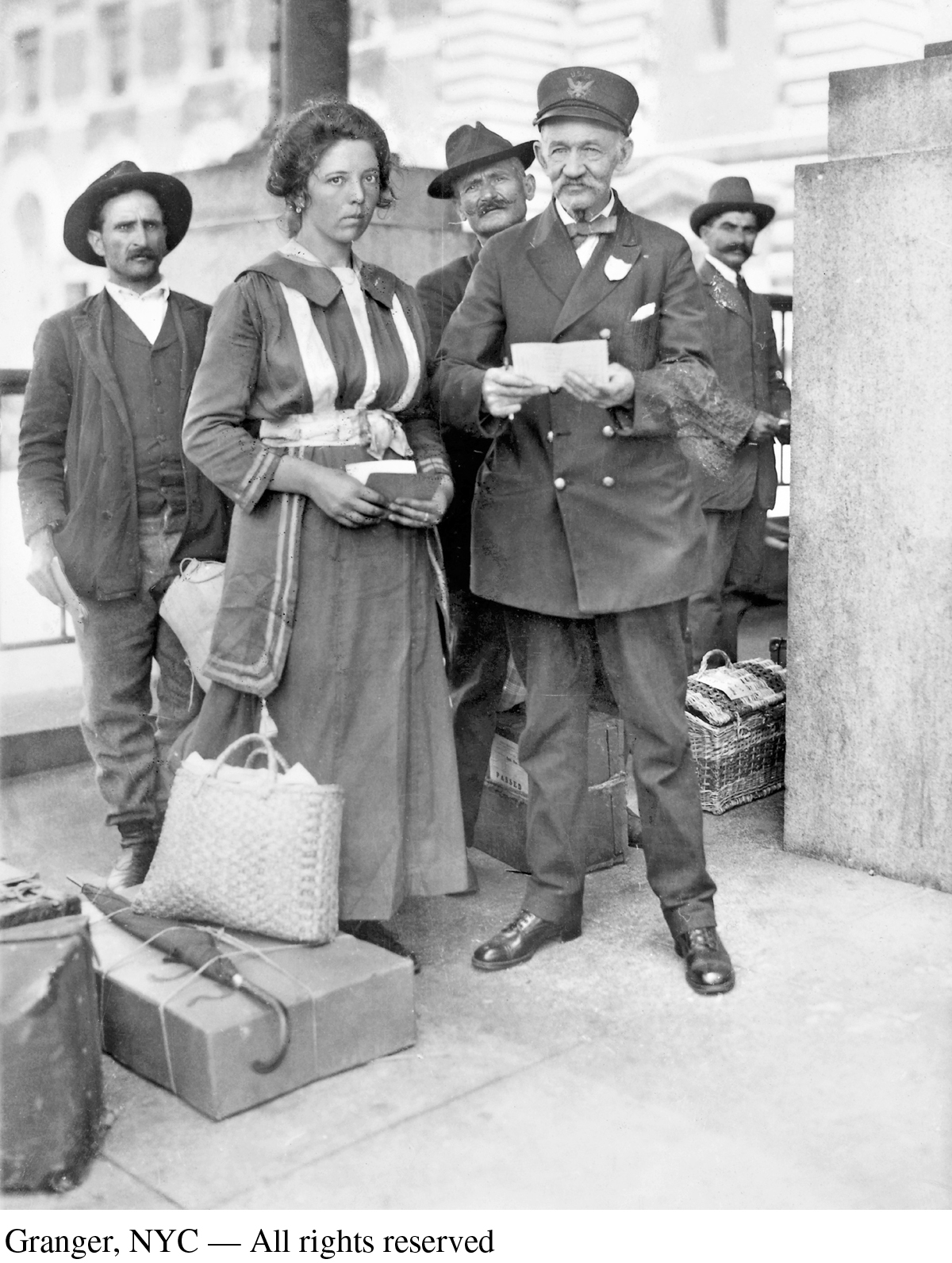

Members of a society who don’t conform to the dominant culture—by way of language, values, lifestyle, or even physical appearance—often form what are called co-cultures: that is, they have their own cultures that co-exist within a dominant cultural sphere (Orbe, 1998). Co-cultures may be based on age, gender, social class, ethnicity, religion, mental and physical ability, sexual orientation, and other unifying elements, depending on the society (Orbe, 1998). U.S. residents who are not members of the dominant culture—people of color, women, members of the LGBTQ community, and so forth—exist as distinct co-cultures, with their own political lobbying groups, Web sites, magazines, and television networks (such as Lifetime, BET, Telemundo, and Here TV).

Because members of co-cultures are (by definition) different from the dominant culture, they develop and use numerous communication practices that help them interact with people in the culturally dominant group (Ramirez-Sanchez, 2008). These differ from one another, depending on whether the co-cultural members engage in assimilation or are attempting to be accepted into the dominant culture. Alternatively, they might get the dominant culture to accommodate their co-cultural identity or separate themselves from the dominant culture altogether. For example, they might use overly polite language with individuals from the dominant culture, and suppress reactions when such people make offensive comments. They might try to excel in all aspects of their professional and personal lives to counteract negative stereotypes about their co-culture. They might attempt to act, look, and talk like members of the dominant culture, or even openly disparage their own co-culture. Alternatively, members of a co-culture might quietly but clearly express their co-cultural identity through appearance, actions, and words; they might even conform to negative stereotypes in an exaggerated way to shock and scare members from the dominant culture.

How might these communication practices work in real life? Imagine that an African American couple moves to a largely Euro-American suburb. They socialize primarily with their white neighbors, never displaying any indication of their African American heritage other than their skin color. Meanwhile, their son dresses in sagging pants, wears a do-rag, and blasts gangsta rap through Beats headphones. Through these behaviors, he actively strives to conform to stereotypes about young black males. Despite their differences, all these behaviors have the same goal: managing the tension between African American co-culture and the dominant Euro-American culture.

As discussed in Chapter 3, our perceptions of shared attitudes, beliefs, and values based on cultural and co-cultural affiliations can lead us to classify those who are similar to us as ingroupers and those who are different as outgroupers. This, however, can be a dangerous trap. Just because someone shares a particular co-culture with you (say, your race or sexual orientation), it doesn’t mean that you are truly the same. For example, you and a classmate might both be “white” (the same race), but you may be Irish Catholic and she may be Russian Jewish, with a host of different ethnic and religious factors that affect your interpersonal communication. In fact, you may be more similar to an Asian American classmate who shares your religious dedication and your socioeconomic background.

focus on CULTURE: Millennials and Technology

Millennials and Technology

Older adults like to say that “Millennials”—people born between the years 1980 and 2000—are completely different from previous generations in their beliefs, attitudes, values, and communication practices. As New York Times columnist Sheila Marikar (2013) jests, “You know them when you see them. They are tapping on their smartphones, strolling into work late and amassing Instagram followers faster than a twerking cat.” But are Millennials so different from others as to constitute a distinct culture? The largest-scale study of Millennials ever conducted suggests that the answer may be yes (Pew Research Center, 2010).

For one thing, the majority of Millennials (61 percent) believe that they are a distinct and unique group. The data support this self-perception along many indicators: Millennials are more likely than members of previous generations to report close relationships with their parents; less likely to get married in their 20s; and more likely to have body piercings in places other than earlobes. But the primary point of generational difference is technology. On virtually every measure of Internet and cell-phone use—including texting, tweeting, posting videos and photos, e-mail, and wireless use—Millennials score substantially higher than older adults. For example, 75 percent of Millennials have personal profiles on social networking sites, compared to only one-third of older adults. And the younger the Millennial, the higher the use, especially with regard to texting.

But it’s not just their use of technology that sets Millennials culturally apart; it’s their view of it. Millennials are more likely than other generations to say that technology connects family and friends, rather than creates isolation and distance. And Millennials are much more likely than other generations to be tethered to their cell phones. A whopping 83 percent of Millennials place their cell phones on, or right next to, their beds while sleeping, a number far higher than that of older adults. As the Pew Research Center report (2010) concludes, Millennials “are history’s first ‘always connected’ generation. Steeped in digital technology and social media, they treat their multi-tasking hand-held gadgets almost like a body part” (p. 8).

discussion questions

Given that culture is “an established, coherent set of beliefs, attitudes, values, and practices shared by a large group of people,” are Millennials a distinct culture? If so, what are their principal points of cultural uniqueness? If they are not a distinct culture, why not?

Does technological literacy, and attitudes toward technology, create a cultural divide between people?

PREJUDICE

Because people tend to shy away from interacting with outgroupers, they may rely on stereotypes to form judgments about them. As you learned in Chapter 3, stereotypes are a way to categorize people into a social group and then evaluate them based on information you have related to this group. Stereotypes play a big part in how you form impressions about others during the perception process. This is especially true for racial and gender characteristics, since they are among the things you notice first when encountering others. But when stereotypes reflect rigid attitudes toward groups and their members, they become prejudice (Ramasubramanian, 2010).

Because prejudice is rooted in stereotypes, it can vary depending on whether those stereotypes are positive or negative. According to the Stereotype Content Model (Fiske, Cuddy, Glick, & Xu, 2002), prejudice centers on two judgments made about others: how warm and friendly they are and how competent they are. These judgments create two possible kinds of prejudice: benevolent and hostile.

skillspractice

Addressing Prejudice

Become a less prejudiced communicator.

Recognize that we all have prejudices, even if they seem harmless (as in “Men who watch football are lazy”).

Commit to having an open mind about individuals belonging to groups about which you hold prejudiced beliefs.

Seek interpersonal communication encounters with members of these groups. Get to know individuals, and don’t be afraid to ask questions.

Evaluate your own communication. Do you communicate with group members in ways that set them up to confirm your prejudiced beliefs?

Benevolent prejudice occurs when people think of a particular group as inferior but also friendly and competent. For instance, someone judges a group as “primitive,” “helpless,” and “ignorant” but attributes their “inferiority” to forces beyond their control, such as lack of education, technology, or wealth (Ramasubramanian, 2010). Thus, although the group is thought of negatively, it also triggers feelings of sympathy (Fiske et al., 2002). If you ever find yourself thinking about a group of people who you consider “inferior” but who you also think could improve themselves “if only they knew better,” you’re engaging in benevolent prejudice.

Hostile prejudice happens when people have negative attitudes toward a group of individuals whom they see as unfriendly and incompetent (Fiske et al., 2002). Someone demonstrating hostile prejudice might see the group’s supposed incompetence as intrinsic to the people: “They’re naturally lazy,” “They’re all crazy zealots,” or “They’re mean and violent.” People exhibiting hostile prejudice often believe that the group has received many opportunities to improve (“They’ve been given so much”) but that their innate limitations hold them back (“They’ve done nothing but waste every break that’s been given to them”). Someone who sees a group in these terms can communicate with contempt.

Prejudice, no matter what form, is destructive and unethical. Benevolent prejudice leads you to communicate with others in condescending and disrespectful ways. Hostile prejudice is the root of every exclusionary “ism”: racism, sexism, ageism, classism, ableism, and so on.

Becoming a competent interpersonal communicator requires that you work to overcome prejudices that might influence your communication. However, even if you don’t treat people in a prejudiced way, that doesn’t necessarily mean you’re not prejudiced. Prejudice is rooted in deeply held negative beliefs about particular groups (Ramasubramanian, 2010). If you think you have prejudiced beliefs, use the empathy and perception-checking guidelines discussed in Chapter 3 to help you evaluate and change these views. Learn about the cultures and groups you have prejudiced beliefs about. During interactions, ask members of these groups questions about themselves and listen actively to the answers. This will ease the uncertainty and anxiety you may feel around others who are culturally different from you (Berger & Calabrese, 1975). Finally, be open to new people and experiences; this can result in quality relationships that break down prejudicial barriers.

If you’ve been on the receiving end of prejudice, try not to generalize your experience with that one person (or persons) to all members of the same group. Just because someone of a certain age, gender, ethnicity, or other cultural group behaves badly doesn’t mean that all members of that group do. One of the bitter ironies of prejudice is that it often triggers prejudice as a reaction in the people who have been unfairly treated. This is not to excuse the prejudice or poor communication of others but to help you avoid adding to the vicious cycle of prejudicial communication.