Listening: A Five-Step Process

The scares in horror movies almost always begin with sounds. In my favorite scary film of all, The Babadook (2014), the stage is set for future fright when a mother and son read a children’s story about a monster who announces his arrival with three loud knocks—Dook! Dook! Dook!—only to hear those knocks for real on their own front door. Similar sonic scenes haunt such films as The Conjuring (2013), Paranormal Activity (2007), and The Exorcist (1973). As we sit in the comfort of movie theaters or living rooms, feeling our blood pressure rising, we listen intently to these sounds, trying to understand them and imagining how we would respond if we were in similar situations.

Horror screenwriters use sounds to trigger fear because they know the powerful role that listening plays in our lives. Listening is our most primal and primary communication skill: as children, we develop the ability to listen long before we learn how to speak, read, or write. And as adults, we spend more time listening than we do in any other type of communication activity (Wolvin & Coakley, 1996). But what is often overlooked is that listening is a complex process. Listening involves receiving, attending to, understanding, responding to, and recalling sounds and visual images (Wolvin & Coakley, 1996). When you’re listening to someone, you draw on both auditory and visual cues. In addition to spoken messages, behaviors such as head nodding, smiling, gestures, and eye contact affect how you listen to others and interpret their communication. The process of listening also unfolds over time, rather than instantaneously, through the five steps discussed here.

RECEIVING

You’re Skyping with your brother, who is in the military, stationed overseas. As he talks, you listen to his words and observe his behavior. How does this process happen? As you observe him, light reflects off his skin, clothes, and hair and travels through the lens of your eye to your retina, which sends the images through the optic nerve to your brain, which translates the information into visual images, such as your brother smiling or shaking his head, an effect called seeing. At the same time, sound waves generated by his voice enter your inner ear, causing your eardrum to vibrate. These vibrations travel along acoustic nerves to your brain, which interprets them as your brother’s words and voice tone, an effect known as hearing.

Together, seeing and hearing constitute receiving, the first step in the listening process. Receiving is critical to listening—you can’t listen if you don’t “see” or hear the other person. Unfortunately, our ability to receive is often hampered by noise pollution, sound in the surrounding environment that obscures or distracts our attention from auditory input. Sources of noise pollution include crowds, road and air traffic, construction equipment, and music.

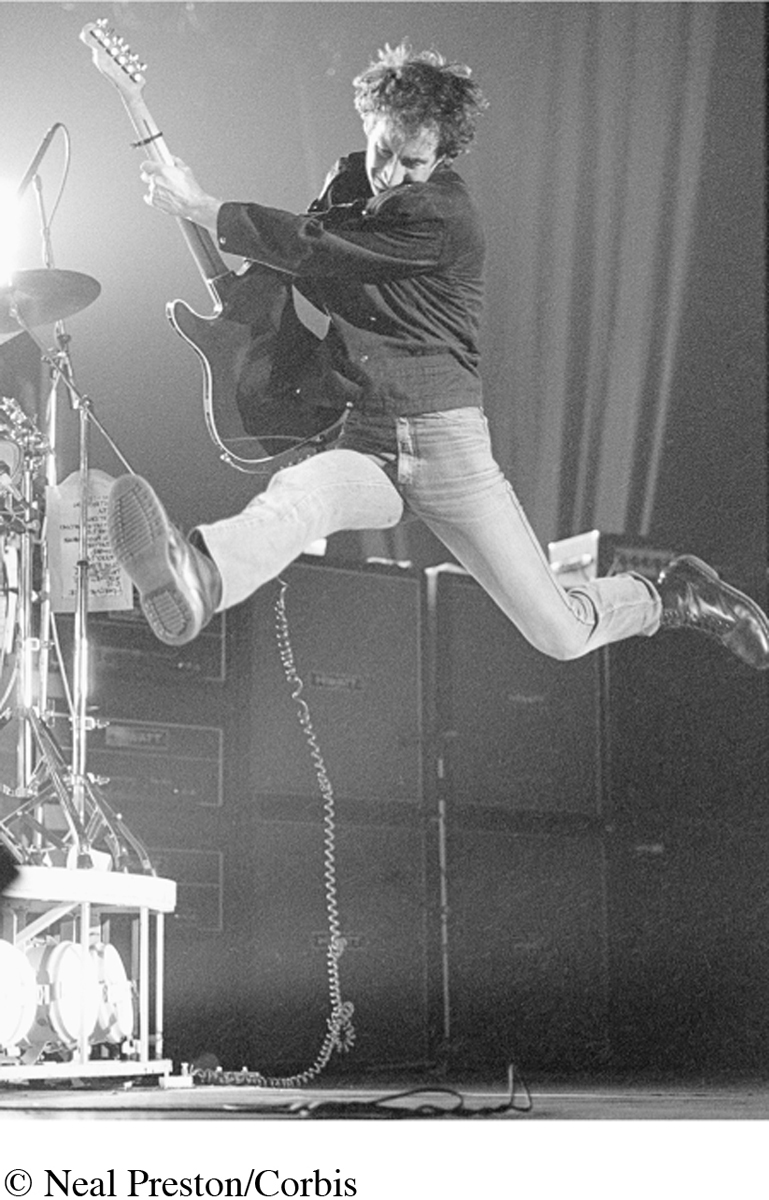

Although noise pollution is inescapable, especially in large cities, some people intentionally expose themselves to intense levels of noise pollution. This can result in hearing impairment, the restricted ability to receive sound input across the humanly audible frequency range. For example, research suggests that more than 40 percent of college students have measurable hearing impairment due to loud music in bars, home stereos, headphones, and concerts, but only 8 percent believe that it is a “big problem” compared with other health issues (Chung, Des Roches, Meunier, & Eavey, 2005). One study of rock and jazz musicians found that 75 percent suffered substantial hearing loss from exposure to chronic noise pollution (Kaharit, Zachau, Eklof, Sandsjo, & Moller, 2003).

self-reflection

Think of the most recent instance in which you were truly frightened. What triggered your fear? Was it a noise you heard, something someone told you, or something you saw? What does this tell you about the primacy of listening in shaping intense emotions?

You can enhance your ability to receive—and improve your listening as a result—by becoming aware of noise pollution and adjusting your interactions accordingly. Practice monitoring the noise level in your environment during your interpersonal encounters, and notice how it impedes your listening. When possible, avoid interactions in loud and noisy environments, or move to quieter locations when you wish to exchange important information with others. If you enjoy loud music or live concerts, always use ear protection to ensure your auditory safety. As a lifelong musician, I myself never practice, play a gig, or attend a concert without earplugs.

ATTENDING

Attending, the second step in the listening process, involves devoting attention to the information you’ve received. If you don’t attend to information, you can’t go on to interpret and understand it, or respond to it (Kahneman, 1973). The extent to which you attend to received information is determined largely by its salience—the degree to which it seems especially noticeable and significant. As discussed in Chapter 3, we view information as salient when it’s visually or audibly stimulating, unexpected, or personally important (Fiske & Taylor, 1991). We have only limited control over salience; whether people communicate in stimulating, unexpected, or important ways is largely determined by them, not us. However, we do control our attention level. To improve your attention, consider trying two things: limiting your multitasking and elevating your attention.

Limiting Multitasking Online One way to improve attention is to limit the amount of time you spend each day multitasking online—using multiple forms of technology at once, each of which feeds you an unrelated stream of information (Ophir, Nass, & Wagner, 2012). An example of such multitasking is writing a class paper on your computer while also tweeting on your phone, Facebook chatting with several friends, watching TV, playing an online computer game, and texting family members. Stanford psychologist Clifford Nass has found that habitual multitaskers are extremely confident in their ability to perform at peak levels on the tasks they simultaneously juggle (Glenn, 2010). However, their confidence is misplaced. Multitaskers perform substantially worse on tasks compared with individuals who focus their attention on only one task at a time (Ophir et al., 2012). As a specific example, college students who routinely surf social networking sites and text while they are doing their homework suffer substantially lower overall GPAs than do students who limit their multitasking while studying (Juncoa & Cotton, 2012).

Why is limiting multitasking online important for improving attention? Because multitasking erodes your capacity for sustaining focused attention (Jackson, 2008). Cognitive scientists have discovered that our brains adapt to the tasks we regularly perform during our waking hours, an effect known as brain plasticity (Carr, 2010). In simple terms, we “train our brains” to be able to do certain things through how we live our daily lives. People who spend much of their time, day after day, shifting attention rapidly between multiple forms of technology train their brains to focus attention only in brief bursts. The consequence is that they lose the ability to focus attention for long periods of time on just one task (Jackson, 2008). For example, one study of high school and college students found that habitual multitaskers couldn’t focus their attention on a single task for more than five minutes at a time without checking social networking sites or phone messages (Rosen, Carrier, & Cheever, 2013). What’s more, habitual multitaskers set themselves up for distraction: they routinely have multiple apps running, which enhances the likelihood of distraction (Rosen et al., 2013).

Not surprisingly, habitual multitaskers have great difficulty listening, as listening requires extended attention (Carr, 2010). Limiting your multitasking and spending at least some time each day focused on just one task (such as reading, listening to music, or engaging in prayer or meditation), without technological distractions, help train your brain to be able to sustain attention. In addition, when you’re in a high-stakes setting, one in which important information is being shared, it’s essential that you limit access to and use of multiple apps, to avoid the attention impairment that comes with simply having such distractions present (Rosen et al., 2013). To gauge the degree to which multitasking has impacted your attention, take the Self-Quiz “Multitasking and Attention.”

skillspractice

Elevating Attention

Focusing your attention during interpersonal encounters

Identify an important person whom you find it difficult to listen to.

List factors—fatigue, time pressure—that impede your attention when you’re interacting with this person.

Before your next encounter with the individual, address factors you can control.

During the encounter, increase the person’s salience by reminding yourself of his or her importance to you.

As the encounter unfolds, practice mental bracketing to stay focused on your partner’s communication.

Elevating Attention The second thing you can try to improve your attention is to elevate it, by following these steps (Marzano & Arredondo, 1996). First, develop awareness of your attention level. During interpersonal interactions, monitor how your attention naturally waxes and wanes. Notice how various factors, such as fatigue, stress, or hunger, influence your attention. Second, take note of encounters in which you should listen carefully but that seem to trigger low levels of attention. These might include interactions with parents, teachers, or work managers, or situations such as family get-togethers, classroom lectures, or work meetings. Third, consider the optimal level of attention required for adequate listening during these encounters. Fourth, compare the level of attention you observed in yourself versus the level of attention that is required, identifying the attention gap that needs to be bridged for you to improve your attention.

Finally, and most important, elevate your level of attention to the point necessary to take in the auditory and visual information you’re receiving. You can do this in several ways. Before and during an encounter, boost the salience of the exchange by reminding yourself of how it will impact your life and relationships. Take active control of the factors that may diminish your attention. When possible, avoid important encounters when you are overly stressed, hungry, ill, fatigued, or under the influence of alcohol; such factors substantially impair attention. If you have higher energy levels in the morning or early in the week, try to schedule attention-demanding activities and encounters during those times. If you find your attention wandering, practice mental bracketing—systematically putting aside thoughts that aren’t relevant to the interaction at hand. When irrelevant thoughts arise, let them pass through your conscious awareness and drift away, without allowing them to occupy your attention fully.

UNDERSTANDING

While serving with her National Guard unit in Iraq, Army Specialist Claudia Carreon suffered a traumatic brain injury (TBI).1 The injury wiped her memory clean. She could no longer remember major events or people from her past, including her husband and her 2-year-old daughter. However, because she seemed physically normal, her TBI went unnoticed and she returned to duty. A few weeks later, Carreon received an order from a commanding officer, but she couldn’t understand it and shortly afterward forgot it. She was subsequently demoted for “failure to follow an order.” When Army doctors realized that she wasn’t being willfully disobedient but instead simply couldn’t understand or remember orders, her rank was restored, and Carreon was rushed to the Army’s Polytrauma Center in Palo Alto, California. Now Carreon, like many other veterans who have suffered TBIs, carries with her captioned photos of loved ones and a special handheld personal computer to help her remember people and make sense of everyday conversations.

The challenges faced by Claudia Carreon illustrate the essential role that memory plays in shaping the third stage of listening. Understanding involves interpreting the meaning of another person’s communication by comparing newly received information against our past knowledge (Macrae & Bodenhausen, 2001). Whenever you receive and attend to new information, you place it in your short-term memory—the part of your mind that temporarily houses the information while you seek to understand its meaning. While the new information sits in your short-term memory, you call up relevant knowledge from your long-term memory—the part of your mind devoted to permanent information storage. You then compare relevant prior knowledge from your long-term memory with the new information in your short-term memory to create understanding. In Claudia Carreon’s case, her long-term memory was largely erased by her injury. Consequently, whenever she hears new information, she has no foundation from which to make sense of it.