Nonverbal Communication Codes

One reason nonverbal communication contains such rich information is that during interpersonal encounters, we use many different aspects of our behavior, appearance, and surrounding environment simultaneously to communicate meaning. You can greatly strengthen your nonverbal communication skills by understanding nonverbal communication codes, the different means used for transmitting information nonverbally (Burgoon & Hoobler, 2002). Scholars distinguish seven nonverbal communication codes, summarized in Table 8.1.

| Code | Description |

|---|---|

| Kinesics | Visible body movements, including facial expressions, eye contact, gestures, and body postures |

| Vocalics | Vocal characteristics, such as loudness, pitch, speech rate, and tone |

| Haptics | Duration, placement, and strength of touch |

| Proxemics | Use of physical distance |

| Physical appearance | Appearance of hair, clothing, body type, and other physical features |

| Artifacts | Personal possessions displayed to others |

| Environment | Structure of physical surroundings |

COMMUNICATING THROUGH BODY MOVEMENTS

At age 16, Tyra Banks began doing fashion shows in Europe for designers such as Chanel and Fendi. She subsequently appeared in Elle and Vogue and was the first African American woman to grace the cover of GQ. But what catapulted her to the top of the global modeling industry was not just her beauty; it was her unique self-awareness of, and control over, her body movements. For example, Tyra distinguishes 275 different smiles she uses when modeling, and she teaches her protégés to practice seven basic smiles on her show, America’s Next Top Model. One of these smiles doesn’t involve the mouth at all, just the eyes, which Tyra calls a smize. Another smile uses body posture and movement—shifting her shoulder position sideways and downward, and turning her head toward the listener. These different smiles all reflect specific emotions or situations, from anger to surprise.

Tyra Banks’s superlative use of nonverbal skill in her modeling exemplifies the power of kinesics (from the Greek kinesis, meaning “movement”)—visible body movements. Kinesics is the richest nonverbal code in terms of its power to communicate meaning, and it includes most of the behaviors we associate with nonverbal communication: facial expressions, eye contact, gestures, and body postures.

Facial Expression “A person’s character is clearly written on the face.” As this traditional Chinese saying suggests, the face plays a pivotal role in shaping our perception of others. In fact, some scholars argue that facial cues rank first among all forms of communication in their influence on our interpersonal impressions (Knapp & Hall, 2002). We use facial expressions to communicate an endless stream of emotions, and we make judgments about what others are feeling by assessing their facial expressions. Our use of emoticons (such as  and

and  ) to communicate attitudes and emotions online testifies to our reliance on this type of kinesics. The primacy of the face even influences our labeling of interpersonal encounters (“face-to-face”) and Web sites devoted to social networking (“Facebook”).

) to communicate attitudes and emotions online testifies to our reliance on this type of kinesics. The primacy of the face even influences our labeling of interpersonal encounters (“face-to-face”) and Web sites devoted to social networking (“Facebook”).

Eye Contact Eye contact serves many purposes during interpersonal communication. We use our eyes to express emotions, signal when it’s someone else’s turn to talk, and show others that we’re listening to them. We also demonstrate our interest in a conversation by increasing our eye contact, or signal relationship intimacy by locking eyes with a close friend or romantic partner.

Eye contact can convey hostility as well. One of the most aggressive forms of nonverbal expression is prolonged staring—fixed and unwavering eye contact of several seconds’ duration (typically accompanied by a hostile facial expression). Although women seldom stare, men use this behavior to threaten others, invite aggression (staring someone down to provoke a fight), and assert their status (Burgoon, Buller, & Woodall, 1996).

Gestures Imagine that you’re driving to an appointment and someone is riding right on your bumper. Scowling at the offender in your rearview mirror, you’re tempted to raise your middle finger and show it to the other driver, but you restrain yourself. The raised finger is an example of a gesture, a hand motion used to communicate messages (Streek, 1993). Flipping someone the bird falls into a category of gestures known as emblems, which represent specific verbal meanings (Ekman, 1976). With emblems, the gesture and its verbal meaning are interchangeable. You can say the words or use the gesture, and you’ll send the same message.

Unlike emblems, illustrators accent or illustrate verbal messages. You tell your spouse about a rough road you recently biked, and as you describe the bumpy road you bounce your hand up and down to illustrate the ride.

Regulators control the exchange of conversational turns during interpersonal encounters (Rosenfeld, 1987). Listeners use regulators to tell speakers to keep talking, repeat something, hurry up, or let another person talk (Ekman & Friesen, 1969). Speakers use them to tell listeners to pay attention or to wait longer for their turn. Common examples include pointing a finger while trying to interrupt and holding a palm straight up to keep a person from interrupting. During online communication, abbreviations such as BRB (“be right back”) and JAS (“just a second”) serve as textual substitutes for gestural regulators.

Adaptors are touching gestures often unconsciously made that serve a psychological or physical purpose (Ekman & Friesen, 1969). For example, you smooth your hair to make a better impression while meeting a potential new romantic partner.

skillspractice

Communicating Immediacy

Using kinesics to communicate immediacy during interpersonal encounters

Initiate an encounter with someone whom you want to impress as an attentive and involved communicator (such as a new friend or a potential romantic partner).

While talking, keep your facial expression pleasant. Don’t be afraid to smile!

Make eye contact, especially while listening, but avoid prolonged staring.

Directly face the person, keep your back straight, lean forward, and keep your arms open and relaxed (rather than crossing them over your chest).

Use illustrators to enhance important descriptions, and regulators to control your exchange of turns.

Posture The fourth kinesic is your body posture, which includes straightness of back (erect or slouched), body lean (forward, backward, or vertical), straightness of shoulders (firm and broad or slumped), and head position (tilted or straight up). Your posture communicates two primary messages to others: immediacy and power (Mehrabian, 1972). Immediacy is the degree to which you find someone interesting and attractive. Want to nonverbally communicate that you like someone? Lean forward, keep your back straight and your arms open, and hold your head up, facing the person when talking. Want to convey dislike? Lean back, close your arms, and look away.

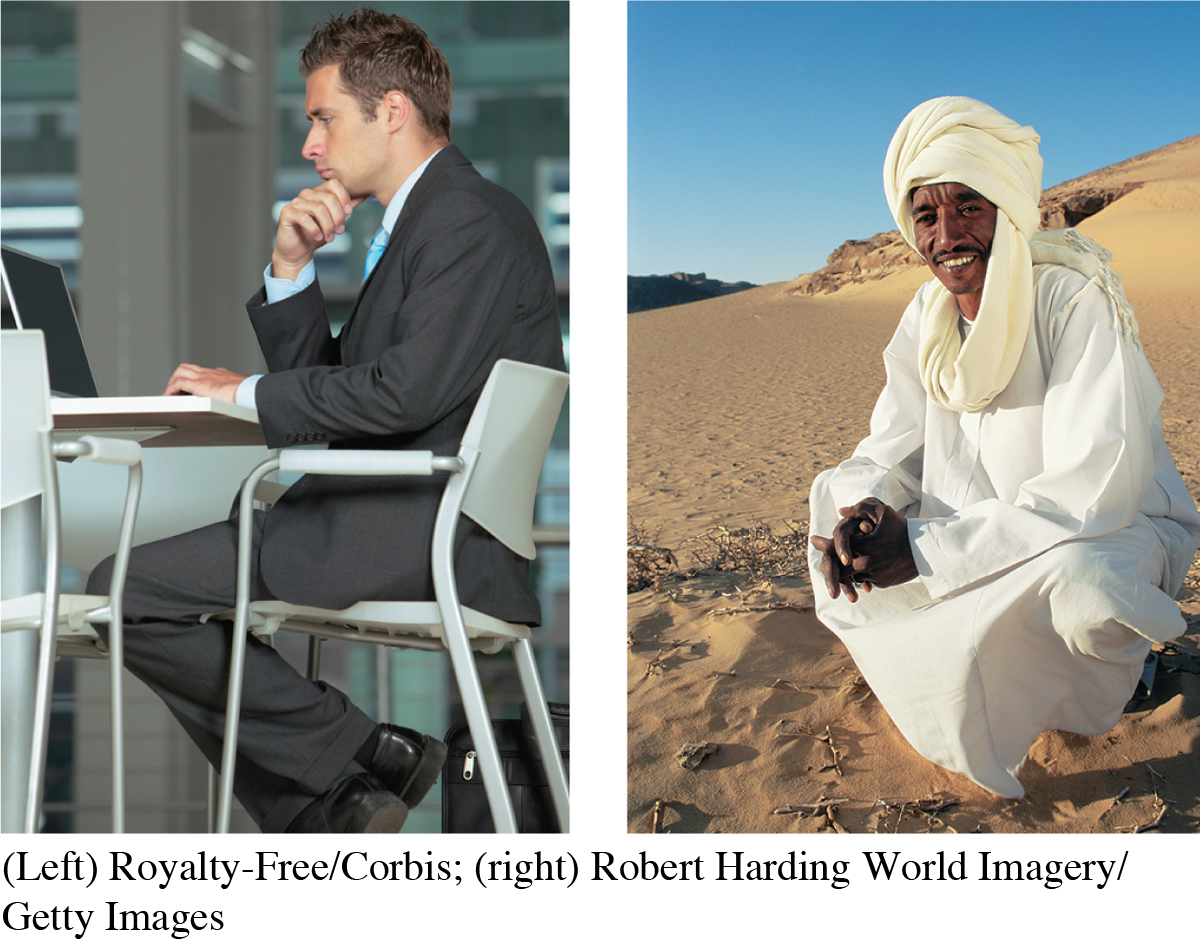

Power is the ability to influence or control other people or events (discussed in detail in Chapter 9). Imagine attending two job interviews in the same afternoon. The first interviewer sits upright, with a tense, rigid body posture. The second interviewer leans back in his chair, with his feet up on his desk and his hands behind his head. Which interviewer has more power? Most Americans would say the second. In the United States, high-status communicators typically use relaxed postures (Burgoon et al., 1996), but in Japan, the opposite is true. Japanese display power through erect posture and feet planted firmly on the floor.

COMMUNICATING THROUGH VOICE

Grammy winner T-Pain has collaborated with an enviable who’s who list of rap, hip-hop, and R&B stars: Ludacris, Lil Wayne, Chris Brown, Kanye West, and a host of others. But what makes T-Pain unique, and his songs so instantly recognizable, is his pioneering work with the pitch-correction program Auto-Tune. He was one of the first musicians to realize that Auto-Tune could be used not only to subtly correct singing errors but to alter one’s voice entirely. Running his vocals through the program, his normally full, rich voice becomes thin and reedy sounding, jumping in pitch precisely from note to note without error. The result is a sound that is at once musical yet robotic. The style is so popular that he even released an iPhone app called “I Am T-Pain,” allowing fans to record and modify their own voices so that they could sound like him.

The popularity of T-Pain’s vocal manipulations illustrates the impact that vocalics—vocal characteristics we use to communicate nonverbal messages—has on our impressions. Indeed, vocalics rival kinesics in their communicative power (Burgoon et al., 1996) because our voices communicate our social, ethnic, and individual identities to others. Consider a study that recorded people from diverse backgrounds answering a series of small-talk questions, such as “How are you?” (Harms, 1961). People who listened to these recordings were able to accurately judge participants’ ethnicity, gender, and social class, often within only 10 to 15 seconds, based solely on their voices. Vocalics strongly shape our perception of others when we first meet them. If we perceive a person’s voice as calm and smooth (not nasal or shrill), we are more likely to view him or her as attractive; form a positive impression; and judge the person as extraverted, open, and conscientious (Zuckerman, Hodgins, & Miyake, 1990).

When we interact with others, we typically experience their voices as a totality—they “talk in certain ways” or “have a particular kind of voice.” But people’s voices are actually complex combinations of four characteristics: tone, pitch, loudness, and speech rate.

Tone The most noticeable aspect of T-Pain’s vocals is their unnatural, computerized tone. Tone is the most complex of human vocalic characteristics and involves a combination of richness and breathiness. You can control your vocal tone by allowing your voice to resonate deep in your chest and throat—achieving a full, rich tone that conveys an authoritative quality while giving a formal talk, for example. By contrast, letting your voice resonate through your sinus cavity creates a more whiny and nasal tone—often unpleasant to others. Your use of breath also affects tone. If you expel a great deal of air when speaking, you convey sexiness. If you constrict the airflow when speaking, you create a thin and hard tone that may communicate nervousness or anxiety.

English-speakers use vocal tone to emphasize and alter the meanings of verbal messages. Regardless of the words you use, your tone can make your statements serious, silly, or even sarcastic, and you can shift tone extremely rapidly to convey different emphases. For example, when talking with your friends, you can suddenly switch from your normal tone to a much more deeply chest-resonant tone to mimic a pompous politician, then nearly instantly constrict your airflow and make your voice sound more like SpongeBob SquarePants. In online communication, we use italics to convey tone change (“I can’t believe you did that”).

Pitch You’re introduced to two new coworkers, Rashad and Paul. Both are tall and muscular. Rashad has a deep, low-pitched voice; Paul, an unusually high-pitched one. How do their voices shape your impressions of them? If you’re like most people, you’ll conclude that Rashad is strong and competent, while Paul is weak (Spender, 1990). Not coincidentally, people believe that women have higher-pitched voices than men and that women’s voices are more “shrill” and “whining” (Spender, 1990). But although women across cultures do use higher pitch than men, most men are capable of using a higher pitch than they normally do but choose to intentionally limit their range to lower pitch levels to convey strength (Brend, 1975).

Loudness Consider the following sentence: “Will John leave the room” (Searle, 1965). Say the sentence aloud, each time emphasizing a different word. Notice that emphasizing one word over another can alter the meaning from statement to question to command, depending on which word is emphasized (“WILL John leave the room” versus “Will JOHN leave the room”).

self-reflection

Think about someone you know whose voice you find funny, strange, or irritating. What is it about this person’s voice that fosters your negative impression? Is it ethical to judge someone solely from his or her voice? Why or why not?

Loudness affects meaning so powerfully that people mimic it online by USING CAPITAL LETTERS TO EMPHASIZE CERTAIN POINTS. Indeed, people who extensively cap are punished for being “too loud.” For example, a member of a music Web site I routinely visit accidentally left his Caps Lock key on while posting, and all of his messages were capped. Several other members immediately pounced, scolding him, “Stop shouting!”

Speech Rate The final vocal characteristic is the speed at which you speak. Talking at a moderate and steady rate is often considered a critical technique for effective speaking. Public-speaking educators urge students to “slow down,” and people in conversations often reduce their speech rate if they believe that their listeners don’t understand them. But MIT computer science researcher Jean Krause found that speech rate is not the primary determinant of intelligibility (Krause, 2001). Instead, it’s pronunciation and articulation of words. People who speak quickly but enunciate clearly are just as competent communicators as those who speak moderately or slowly.