Competently Managing Your Nonverbal Communication

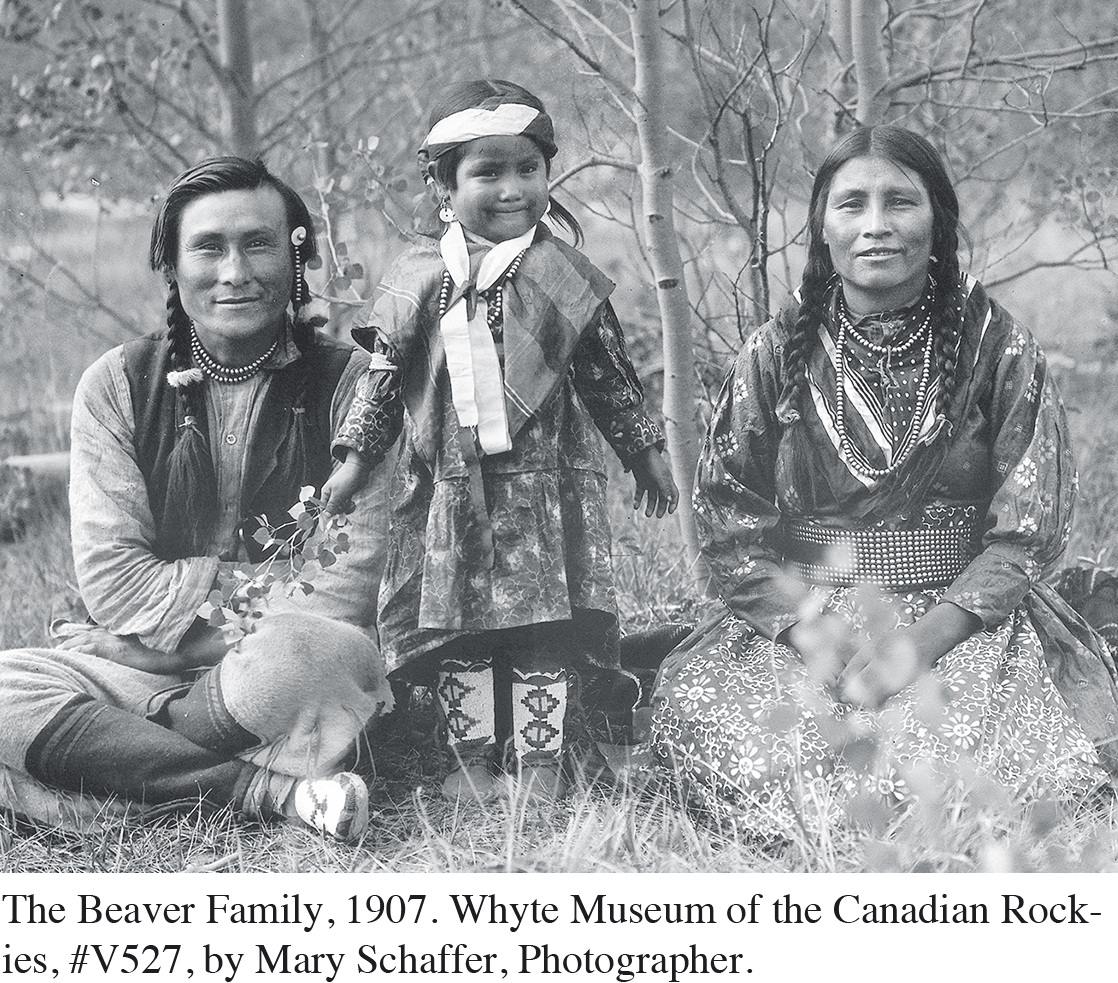

As you interact with others, you use various nonverbal communication codes naturally and simultaneously. Similarly, you take in and interpret others’ nonverbal communication instinctively. Look again at the Beaver family photo (on p. 248). While viewing this image, you probably don’t think, “What’s Samson’s mouth doing?” or “Gee, Frances’s arm is touching Samson’s shoulder.” When it comes to nonverbal communication, although all the parts are important, it’s the overall package that delivers the message.

Given the nature of nonverbal communication, we think it’s important to highlight some general guidelines for how you can competently manage your nonverbal communication. In this chapter, we’ve offered very specific advice for improving your use of particular nonverbal codes. But we conclude with three principles for competent nonverbal conduct, which reflect the three aspects of competence first introduced in Chapter 1: effectiveness, appropriateness, and ethics.

First, when interacting with others, remember that people view your nonverbal communication as at least as important as what you say, if not more so. Although you should endeavor to build your active listening skills (Chapter 6) and use of cooperative language (Chapter 7), bear in mind that people will often assign the greatest weight to what you do nonverbally.

Second, be sensitive to the demands of interpersonal situations. For example, if an interaction seems to call for more formal or more casual behavior, adapt your nonverbal communication accordingly. Remind yourself, if necessary, that being interviewed for a job, sharing a relaxed evening with your roommate, and deepening the level of intimacy in a love relationship all call for different nonverbal messages. You can craft those messages through careful use of the many different nonverbal codes available to you.

Finally, remember that verbal communication and nonverbal communication flow with each other. Your experience of nonverbal communication from others and your nonverbal expression to others are fundamentally fused with the words you and they choose to use. As a consequence, you cannot become a skilled interpersonal communicator by focusing time, effort, and energy only on verbal or only on nonverbal elements. Instead, you must devote yourself to both, because it is only when both are joined as a union of skills that more competent interpersonal communication ability is achieved.

POSTSCRIPT

Reflect on the postures, dress, use of space, eye contact, and facial expressions depicted in the Beaver family photo. Then think about how nonverbal communication shapes your life. What judgments do you make about others, based on their scowls and smiles? their postures? their appearance and voice? Do you draw accurate conclusions about certain groups of people based on their nonverbal communication? How do others see you? As you communicate with others throughout a typical day, what do your facial expressions, posture, dress, use of space, and eye contact convey?

We began this chapter with a family of smiles. The smile is one of the simplest, most commonplace expressions. Yet like so many nonverbal expressions, the smile has the power to fundamentally shift interpersonal perceptions. In the case of the Beaver family, seeing the smiles that talking with a friend evoked 100 years ago helps erase more than a century of Native American stereotypes. But the power of the Beaver family’s smiles goes beyond simply remedying a historical distortion. It highlights the power that even your simplest nonverbal communication has in shaping and shifting others’ perceptions of you.