Introduction to Chapter 2

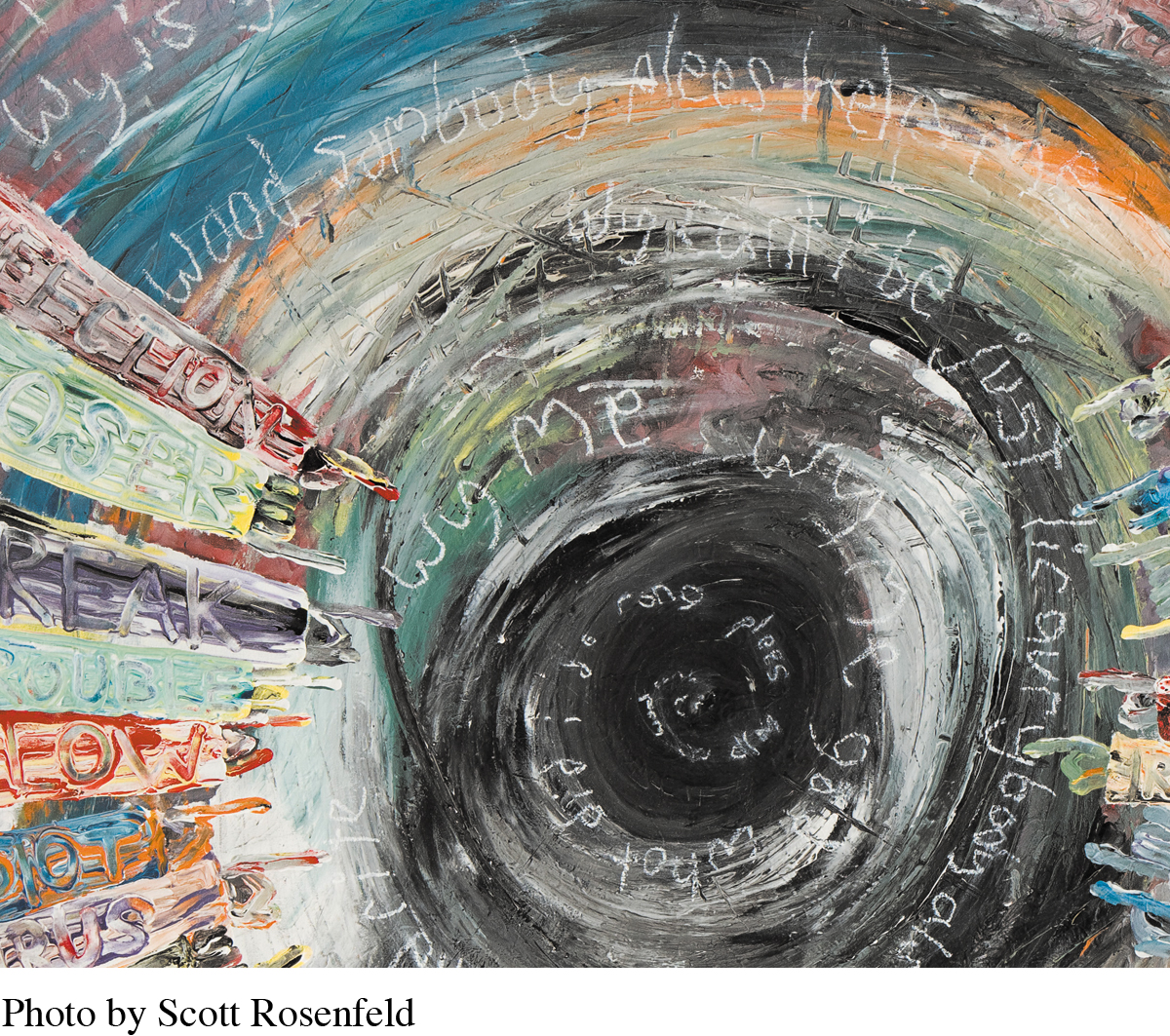

A rtist Eric Staib describes his 2002 painting labeled as a self-portrait. “It depicts my feelings about how my peers saw me when I was growing up. The hands pointing, words said under people’s breath. You can tell what they’re thinking: you’re an idiot, you’re stupid, you’re a joke.”1

By the time Eric was in third grade, he knew he was different. Whereas his classmates progressed rapidly in reading and writing, Eric couldn’t make sense of words on the written page. But it wasn’t until fifth grade that Eric was finally given a label for his difference: learning disabled, or LD. The LD label stained Eric’s sense of self, making him feel ashamed. His low self-esteem spread outward, constraining his communication and relationships. “My whole approach was Don’t get noticed! I’d slouch down in class, hide in my seat. And I would never open up to people. I let nobody in.”

Frustrated with the seemingly insurmountable challenges of reading and writing, Eric channeled intense energy into art. By eleventh grade, Eric had the reading and writing abilities of a fifth grader but managed to pass his classes through hard work and artistic ability. He graduated from high school with a D average.

Many of Eric’s peers with learning disabilities had turned to substance abuse and dropped out of school, but Eric pursued his education further, taking classes at a local community college. There, something happened that transformed his view of his self, his self-esteem, and the entire course of his life. While taking his first written exam of the semester, Eric knew the answers, but he couldn’t write them down. No matter how hard he focused, he couldn’t convert the knowledge in his head into written words. Rather than complete the exam, he wrote the story of his disability on the answer sheet, including his struggles with reading and writing and the pain associated with being labeled LD. He turned in his exam and left. Eric’s professor took his exam to the college dean, and the two of them called Eric to the dean’s office. They told him, “You need help, and we’re going to help you.” Their compassion changed Eric’s life. Eric’s professor arranged for Eric to meet with a learning specialist, who immediately diagnosed him as dyslexic. As Eric explains, “For the first time in my life, I had a label for myself other than ‘learning disabled.’ To me, the LD label meant I couldn’t learn. But dyslexia was different. It could be overcome. The specialist taught me strategies for working with my dyslexia, and gave me my most important tool—my Franklin Spellchecker—to check spellings. But most importantly, I was taught that it was OK to be dyslexic.”

Armed with an improving sense of self, Eric went from hiding to asserting himself, “from low self-esteem to being comfortable voicing my opinion, from fear to confidence.” That confidence led him to transfer to a Big Ten university, where he graduated with a degree in studio arts, percussion, and horticulture. He subsequently earned a postgraduate degree in K–12 art education, graduating with a straight-A average.

Eric Staib is now an art instructor in the Midwest and was a 2006 recipient of the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation Power of Art Award, given to the top arts educators in the country each year. He also teaches instructors how to use art to engage students with learning disabilities. What means the most to him is the opportunity to pass down the legacy of his personal transformation. “When I think about my dyslexia, it’s really incredible. What was my greatest personal punishment is now the most profound gift I have to offer to others.”

Every word you’ve ever spoken during an encounter, every act of kindness or cruelty you’ve committed, has the same root source—your self. When you look inward, you are peering into the wellspring from which all your interpersonal actions flow. But even as your self influences your interpersonal communication, it is shaped by your communication as well. Through communicating with others, we learn who we are, what we’re worth, and how we should act. This means that the starting point for improving your communication is to understand your self. In this way, you can begin to clarify your thoughts and feelings about your self; comprehend how these are linked to your interpersonal communication; and develop strategies for enhancing your sense of self, your communication skills, and your interpersonal relationships.

In this chapter, we explore the source of all interpersonal communication: the self. You’ll learn:

The components of self, as well as how critical self-reflection can be used to improve your communication skills and your self-esteem

The ways in which gender, family, and culture shape your sense of self

How to present and maintain a positive self when interacting with others

The importance of online self-presentation

The challenges of managing the self in relationships, including suggestions for successful self-disclosure