Relationship Development and Deterioration

Romantic relationships come together and apart in as many different ways and at as many different speeds as there are partners who fall for each other (Surra & Hughes, 1997). Many relationships are of the “casual dating” variety—they flare quickly, sputter, and then fade. Others endure and evolve with deepening levels of commitment. But all romantic relationships undergo stages marked by distinctive patterns in partners’ communication, thoughts, and feelings. We know these transitions intuitively: “taking things to the next level,” “kicking it up a notch,” “taking a step back,” or “taking a break.” Communication scholar Mark Knapp (1984) modeled these patterns as ten stages: five of “coming together” and five of “coming apart.”

COMING TOGETHER

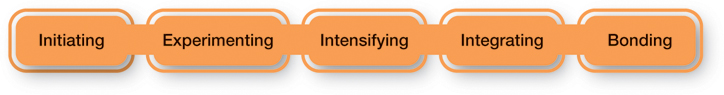

Knapp’s stages of coming together illustrate one possible flow of relationship development (see Figure 11.1). As you read through the stages, keep in mind that these suggest turning points in relationships and are not fixed rules for how involvements should or do progress. Your relationships may go through some, none, or all of these stages. They may skip stages, jump back or forward in order, or follow a completely different and unique trajectory.

Initiating During the initiating stage, you size up a person you’ve just met or noticed. You draw on all available visual information (physical attractiveness, body type, age, ethnicity, gender, clothing, posture) to determine whether you find him or her attractive. Your primary concern at this stage is to portray yourself in a positive light. You also ponder and present a greeting you deem appropriate. This greeting might be in person or online. More than 16 million people in the United States have used online dating sites to meet new partners (Heino, Ellison, & Gibbs, 2010).

Experimenting Once you’ve initiated an encounter with someone else (online or face-to-face), you enter the experimenting stage, during which you exchange demographic information (names, majors, where you grew up). You also engage in small talk—disclosing facts you and the other person consider relatively unimportant but that enable you to introduce yourselves in a safe and controlled fashion. As you share these details, you look for points of commonality on which you can base further interaction. This is the “casual dating” phase of romance. For better or worse, most involvements never progress beyond this stage. We go through life experimenting with many people but forming deeper connections with very few.

Intensifying Occasionally, you’ll progress beyond casual dating and find yourself experiencing strong feelings of attraction toward another person. When this happens, your verbal and nonverbal communication becomes increasingly intimate. During this intensifying stage, you and your partner begin to reveal previously withheld information, such as secrets about your past or important life dreams and goals. You may begin using informal forms of address or terms of endearment (“honey” versus “Joe”) and saying “we” more frequently. One particularly strong sign that your relationship is intensifying is the direct expression of commitment. You might do this verbally (“I think I’m falling for you”) or online by marking your profile as “in a relationship” rather than “single.” You may also spend more time in each other’s personal spaces, as well as begin physical expressions of affection, such as hand-holding, cuddling, or sexual activity.

Integrating During the integrating stage, your and your partner’s personalities seem to become one. This integration is reinforced through sexual activity and the exchange of belongings (items of clothing, music, photos, etc.). When you’ve integrated with a romantic partner, you cultivate attitudes, activities, and interests that clearly join you together as a couple—“our song” and “our favorite restaurant.” Friends, colleagues, and family members begin to treat you as a couple—for example, always inviting the two of you to parties or dinners. Not surprisingly, many people begin to struggle with the dialectical tension of connectedness versus autonomy at this stage. As a student of mine once told his partner when describing this stage, “I’m not me anymore; I’m us.”

Bonding The ultimate stage of coming together is bonding, a public ritual that announces to the world that you and your partner have made a commitment to each other. Bonding is something you’ll share with very few people—perhaps only one—during your lifetime. The most obvious example of bonding is marriage.

Bonding institutionalizes your relationship. Before this stage, the ground rules for your relationship and your communication within it remain a private matter, to be negotiated between you and your partner. In the bonding stage, you import into your relationship a set of laws and customs determined by governmental authorities and perhaps religious institutions. Although these laws and customs help solidify your relationship, they can also make your relationship feel more rigid and structured.

COMING APART

Coming together is often followed by coming apart. One study of college dating couples found that across a three-month period, 30 percent broke up (Parks & Adelman, 1983). Similar trends occur in the married adult population: the divorce rate has remained stable at around 40 percent since the early 1980s (Hurley, 2005; Kreider, 2005). This latter number may surprise you because the news media, politicians, and even academics commonly quote the divorce rate as “50 percent.”2 But studies that have tracked couples across time have found that 6 out of 10 North American marriages survive until “death does them part” (Hurley, 2005). Nevertheless, the 40 percent figure translates into a million divorces each year.

In some relationships, breaking up is the right thing to do. Partners have grown apart, they’ve lost interest in each other, or perhaps one person has been abusive. In other relationships, coming apart is unfortunate. Perhaps the partners could have resolved their differences but didn’t make the effort. Thus, they needlessly suffer the pain of breaking up.

Like coming together, coming apart unfolds over stages marked by changes in thoughts, feelings, and communication (see Figure 11.2). But unlike coming together, these stages often entail emotional turmoil that makes it difficult to negotiate skillfully. Learning how to communicate supportively while a romantic relationship is dissolving is a challenging but important part of being a skilled interpersonal communicator.

skillspractice

Differentiating

Overcoming the challenge of differentiating

Identify when you and your romantic partner are differentiating.

Check your perception of the relationship, especially how you’ve punctuated encounters and the attributions you’ve made.

Call to mind the similarities that originally brought you and your partner together.

Discuss your concerns with your partner, emphasizing these similarities and your desire to continue the relationship.

Mutually explore solutions to the differences that have been troubling you.

Differentiating In all romantic relationships, partners share differences as well as similarities. But during differentiating—the first stage of coming apart—the beliefs, attitudes, and values that distinguish you from your partner come to dominate your thoughts and communication (“I can’t believe you think that!” or “We are so different!”).

Most healthy romances experience occasional periods of differentiating. These moments can involve unpleasant clashes and bickering over contrasting viewpoints, tastes, or goals. But you can move your relationship through this difficulty—and thus halt the coming-apart process—by openly discussing your points of difference and working together to resolve them. To do this, review the constructive conflict skills discussed in Chapter 9.

Circumscribing If one or both of you respond to problematic differences by ignoring them and spending less time talking, you enter the circumscribing stage. You actively begin to restrict the quantity and quality of information you exchange with your partner. Instead of sharing information, you create “safe zones” in which you discuss only topics that won’t provoke conflict. Common remarks made during circumscribing include “Don’t ask me about that” and “Let’s not talk about that anymore.”

Stagnating When circumscribing becomes so severe that almost no safe conversational topics remain, communication slows to a standstill, and your relationship enters the stagnating stage. You both presume that communicating is pointless because it will only lead to further problems. People in stagnant relationships often experience a sense of resignation; they feel stuck or trapped. However, they can remain in the relationship for months or even years. Why? Some believe that it’s better to leave things as they are rather than expend the effort necessary to break up or rebuild the relationship. Others simply don’t know how to repair the damage and revive the earlier bond.

Avoiding During the avoiding stage, one or both of you decide that you can no longer be around each other, and you begin distancing yourself physically. Some people communicate avoidance directly to their partner (“I don’t want to see you anymore”). Others do so indirectly—for example, by going out when the partner’s at home, screening cell-phone calls, ignoring texts, and changing their Facebook status from “in a relationship” to “single.”

Terminating In ending a relationship, some people want to come together for a final encounter that gives a sense of closure and resolution. During the terminating stage, couples might discuss the past, present, and future of the relationship. They often exchange summary statements about the past—comments on “how our relationship was” that are either accusations (“No one has ever treated me so badly!”) or laments (“I’ll never be able to find someone as perfect as you”). Verbal and nonverbal behaviors indicating a lack of intimacy are readily apparent, including physical distance between the two individuals and reluctance to make eye contact. The partners may also discuss the future status of their relationship. Some couples may agree to end all contact going forward. Others may choose to maintain some level of physical intimacy even though the emotional side of the relationship is officially over. Still others may express interest in “being friends.”

self-reflection

Have most of your romantic relationships ended by avoiding? Or have you sought the closure provided by terminating? In what situations is one approach to ending relationships better than the other? Is one more ethical?

Many people find terminating a relationship painful or awkward. It’s hard to tell someone else that you no longer want to be involved, and it is equally painful to hear it. Draw on your interpersonal communication skills to best negotiate your way through this dreaded moment. In particular, infuse your communication with empathy—offering empathic concern and perspective-taking (see Chapter 3). Realize that romantic breakups are a kind of death and that it’s normal to experience grief, even when breaking up is the right thing to do. Offer supportive communication (“I’m sorry things had to end this way” or “I know this is going to be painful for both of us”), and use grief management tactics (see Chapter 4). Conversations to terminate a relationship are never pleasant or easy. But the communication skills you’ve learned can help you minimize the pain and damage, enabling you and your former partner to move on to other relationships.

| Maintenance Strategy | Suggested Actions |

|---|---|

| Positivity | Be cheerful and optimistic in your communication. |

| Assurances | Remind your partner of your devotion. |

| Sharing Tasks | Help out with daily responsibilities. |

| Acceptance | Be supportive and forgiving. |

| Self-Disclosure | Share your thoughts, feelings, and fears. |

| Relationship Talks | Make time to discuss your relationship and really listen. |

| Social Networks | Involve yourself with your partner’s friends and family. |