Chapter 1. Parent-Child Culture Clash

Introduction

Introduction

Parent-Child Culture Clash

Activity Objective:

In this activity, you will create your own solution to a difficult relationship problem. You will walk step-by-step through a realistic scenario—critically self-reflecting, considering another person’s perspective, determining best outcomes, and identifying potential roadblocks—and make decisions about how to react.

Click the forward and backward arrows to navigate through the slides. You may also click the above outline button to see an overview of all the slides in this activity.

1.1 1 Background

Communicating across cultural boundaries can be challenging, especially when those boundaries involve differences between children and their elders within the same family. To understand how you might competently manage such a relationship challenge, read the case study in Part 2; then, drawing on all you know about interpersonal communication, work through the problem-solving model in Part 3.

1.2 2 Case Study

You’re a first-generation American, the only child of parents who have deep ties to their home culture. Your mother was never openly affectionate, but when you were growing up, she let you know in many indirect ways that she loved you. But after your father died, that changed. She became coldly authoritarian, and throughout your teen years she bossed you around mercilessly.

Your mother’s cultural beliefs about parental power have become triggers for resentment since you left for college. She chose your major, based on “your obligation to support her in the future,” and even scheduled all your classes your freshman year. You went along with her wishes to preserve harmony, but you resent the fact that you are living the life she wants rather than your own. You’ve come to believe that she has no regard for, or interest in, your dreams and desires.

This past year, three things have happened that may divide you two further. First, you started going to a campus church with some of your American friends, rather than continuing your culture’s religious practices. Although you initially did this as a secret protest against your mother, you’ve enjoyed the experience. Second, you met Devin. Devin is Euro-American, and he impresses you by being outgoing, warm, and funny. You two start dating, but—like the church thing—you don’t tell your mom, because she would never approve. Third, through hanging out with Devin and your other American friends, you begin to question your cultural practices regarding parental power. This comes to a head when, with Devin’s encouragement, you enroll in a couple of interesting electives. These classes make you realize you want to change majors and pursue a very different career path.

Visiting home one weekend, your mother abruptly broaches the topic of your future: “You seem to be drifting from our traditions recently, and this must stop. You’re almost done with school, and you’re no longer a child. The time has come for you to do what is expected of you. I have talked with your uncle about hiring you when you graduate, and he has agreed. And your grandparents back home have made arrangements with another family, our long-time friends, for you to marry one of their children. So, your future is set, and you will bring great honor to this family!”

1.3 3 Your Turn

Think about all you’ve learned thus far about interpersonal communication. Then work through the following five steps. Remember, there are no “right” answers, so think hard about what is the best choice!

Step 1: Reflect on yourself.

What are your thoughts and feelings in this situation? Are your impressions and attributions accurate?

Step 2: Reflect on your partner.

Using perspective-taking and empathic concern, put yourself in your mother’s shoes. What is she thinking and feeling in this situation?

Step 3: Identify the optimal outcome.

Think about your communication and relationship with your mother, as well as the situation surrounding your college experience and future. What’s the best, most constructive relationship outcome possible? Consider what’s best for you and for your mother.

Step 4: Locate the roadblocks.

Taking into consideration your own and your mother’s thoughts and feelings and all that has happened in this situation and in your home life, what obstacles are keeping you from achieving the optimal outcome?

Step 5: Chart your course.

What can you say to your mother to overcome the roadblocks you’ve identified and achieve your optimal outcome?

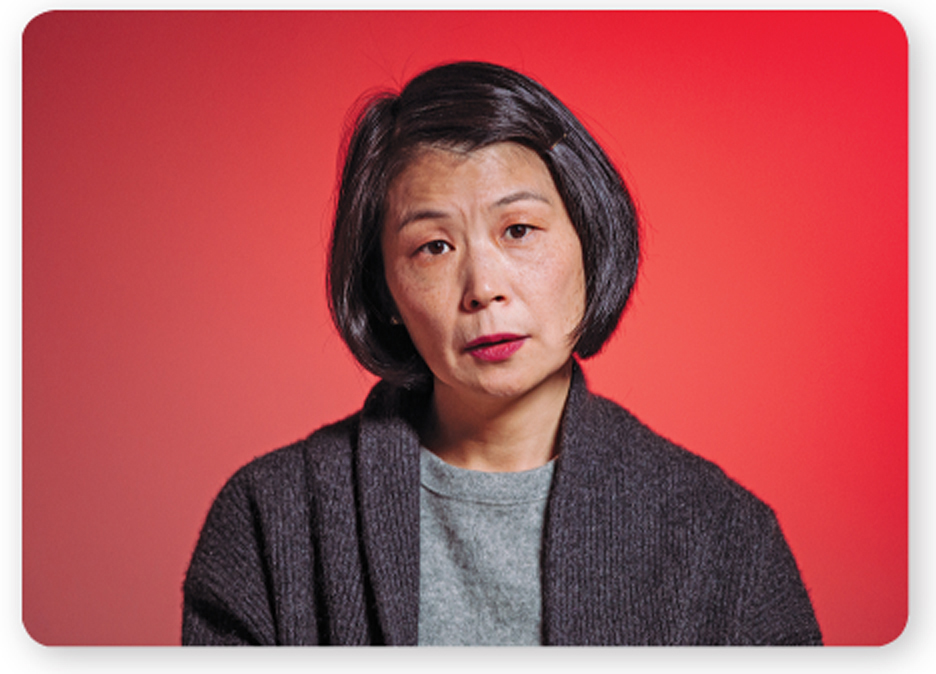

1.4 4 The Other Side

Watch this video in which your mother tells her side of the case study story. As in many real-life situations, this is information to which you did not have access when you were initially crafting your response in Part 3. The video reminds us that even when we do our best to offer competent responses, there always is another side to the story that we need to consider.

Download the Transcript

1.5 5 Interpersonal Competence Self-Assessment

Activity results are being submitted...

Think about the new information offered in your mother’s side of the story and all you’ve learned about interpersonal communication. Drawing upon this knowledge, revisit your earlier responses in Part 3 and assess your own interpersonal communication competence.

Step 1: Evaluate Appropriateness

Being an appropriate interpersonal communicator means matching your communication to situational, relational, and cultural expectations regarding how people should communicate. How appropriate was your response to your mother, given the situation, the history you two share, and your relationship with her? Rate your appropriateness on a scale of 1 to 7, where “1” is least appropriate and “7” is most appropriate.

Step 2: Evaluate Effectiveness

Being an effective interpersonal communicator means using your communication to accomplish self-presentational, instrumental, and relational goals. How effective was your response in dealing with the situation, helping to improve your relationship with your mother, and presenting yourself as a loving son or daughter? Rate your effectiveness on a scale of 1 to 7, where “1” is least effective and “7” is most effective.

Step 3: Evaluate Ethics

Being an ethical communicator means treating others with respect, honesty, and kindness. Given this, how ethical was your response to your mother? Rate your ethics on a scale of 1 to 7, where “1” is least ethical and “7” is most ethical.

Step 4: What Would You Do Differently?

In the real world, there are no “take-backs” or “do-overs.” But part of learning interpersonal communication competence is working to improve your message strategies for dealing with complicated relationship situations. Knowing all that you now know, would you communicate differently to your mother than you did before? If so, write a new message to your mother below. If not, just write “the same” in the box to stick with your initial response.