Chapter 7. Which Professor Should You Take?

Introduction

Survey Design and Scale Construction

In this activity, you will create a survey to measure students’ attitudes about different professors. Just like a researcher, you will determine the best questions to ask, the type of responses to offer, and the best sample to survey.

Dr. Natalie J. Ciarocco, Monmouth University

Dr. David B. Strohmetz, Monmouth University

Dr. Gary W. Lewandowski, Jr., Monmouth University

Something to Think About…

Scenario: It seems to happen every semester. As you register for classes, you find there are several professors teaching the same course. Which professor should you take? Should you register for the section taught by Professor Sandman or the one taught by Professor DeBestie? Sure, you have heard stories about these 2 professors from your friends, but their opinions are mixed. Besides, as a budding scientist, you recognize that anecdotes are not necessarily the best evidence. You could search the Internet to see how past students rated each professor, but, again, this could be problematic. The ratings on these websites could have been generated by disgruntled students or professor “groupies.” There must be a better way to find out how students rate the quality of each professor.

Something to Think About…

We often turn to others for guidance when we are unsure of what to do. The problem is that the information provided might be biased or limited, leading us to make poor decisions. How can you best collect information on students’ opinions about a professor? Science, of course, can help you with this task.

Our Research Question

Your goal is to collect useful information to help students decide which professor to take. To do this, you will need to develop a measure of student opinions of the quality of a professor.

Question 7.1

Which of the research questions below would be best to ask given your research goal?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

Picking the Best Research Approach

Now that you have a research question (“How do I best measure students’ attitudes about different professors?”), you must decide which research approach to use to answer this question. There are 2 research methods you can choose from:

Qualitative Research

Quantitative Research

Question 7.2

Should you use qualitative or quantitative research to answer your question?

| A. |

| B. |

Developing the Best Measure

Now that you have decided to use the quantitative method, your next task is to develop a strategy for measuring students’ attitudes toward a professor. There are 2 types of measures that you can use:

Self-report Measure

Behavioral Measure

Question 7.3

Which type of measure is the better option for assessing students’ attitudes toward a professor?

| A. |

| B. |

Developing the Best Measure

Since you have decided to use a self-report measure to solicit various students’ attitudes toward Professor Sandman and Professor DeBestie, the next step is to decide what type of questions to ask. You have 2 options:

Open-ended Questions

Closed-ended Questions

Question 7.4

What type of questions should you use to measure students’ attitudes toward a specific professor?

| A. |

| B. |

Developing Your Rate-a-Prof Scale

You now know that you are going to use a self-report measure with closed-ended questions to measure students’ attitudes toward Professor Sandman and Professor DeBestie. To accomplish this task, you can develop your own Likert scale (also known as a summated rating scale). Likert scales are frequently used to measure a person’s attitude toward someone or something. In a Likert scale, you ask a person to evaluate a series of statements using a predetermined set of response options. You then sum the responses to these statements to represent the person’s overall attitude toward what is being evaluated.

Question 7.5

How do you want students to evaluate each statement in your Rate-a-Prof Scale?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

Developing Your Rate-a-Prof Scale

You have decided to see to what degree students agree or disagree with various statements about a professor. The next question is, how many response alternatives should you provide them with? 2? 5? 50? 100? Your answer depends on the desired sensitivity of your attitude scale.

Sensitivity

Developing Your Rate-a-Prof Scale

Question 7.6

How many response alternatives do you want to use in your Rate-a-Prof Scale?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Developing Your Rate-a-Prof Scale

You now know how students will evaluate each statement in your Rate-a-Prof Scale. You will use 5 response alternatives: Strongly Agree, Agree, Neither Agree nor Disagree, Disagree, and Strongly Disagree. Each response alternative will be assigned a numerical value that you will use to determine the overall scale score for the students’ rating of the professor. Higher values will have more positive response alternatives, as follows:

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neither Agree nor Disagree | Agree | Strongly Agree |

Developing Your Rate-a-Prof Scale

The next question to consider is, how many statements should you include in your scale to minimize overall error in your measurement of students’ attitudes toward a professor?

Error

Question 7.7

How many statements should you have in your Rate-a-Prof Scale?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

Developing Your Rate-a-Prof Scale

For your Rate-a-Prof Scale, you will ask students to indicate how much they agree or disagree with 5 statements about a specific professor. Your next step is to develop these statements. The key is to pinpoint 5 high-quality items that influence students’ attitudes toward a professor. Based on a quick review of the literature on effective teaching, you decide to ask about 5 things in your scale:

The professor’s teaching strategies

The professor’s expectations for students in the course

The professor’s enthusiasm for teaching

The professor’s ability to generate student interest in the course

The professor’s concern for student problems

You are now ready to write the actual statements for your Rate-a-Prof Scale.

Developing Your Rate-a-Prof Scale

Question 7.8

Which of the following would be the best statement to describe the strategies a professor uses to help students learn the course material?

| A. |

| B. |

Developing Your Rate-a-Prof Scale

Question 7.9

Which of the following would be the best statement to describe the expectations a professor sets for the students in the course?

| A. |

| B. |

Developing Your Rate-a-Prof Scale

Question 7.10

Which of the following would be the best statement to describe the professor’s enthusiasm for teaching?

| A. |

| B. |

Developing Your Rate-a-Prof Scale

You want to have an item asking about how interesting a professor makes the course for students. Because you are asking students to evaluate their professors, there is 1 problem of which you should be aware—namely, how do you ensure that the students fully consider each item rather than simply agreeing (or disagreeing) with all of them? In cases where a student has strong feelings about a particular professor, the student may agree with all of the statements in an effort to give the professor the highest score (or vice versa). This reflects a response bias known as the acquiescent response set.

Acquiescent Response Set

One way to control for the acquiescent response set is to have at least 1 item phrased in the opposite direction compared to the other items. A high rating on this item would have a different meaning than a high rating on the other items. This way, if a student positively evaluates a professor on 1 item, he or she will disagree with the corresponding negative statement. If the student agrees (or disagrees) with this particular statement, then it becomes uncertain whether the student is actually responding to each item or blindly agreeing (or disagreeing) with all of them.

Developing Your Rate-a-Prof Scale

Question 7.11

Which of the following items would be best for evaluating how interesting the professor makes a course, while trying to control for a potential acquiescent response set bias?

| A. |

| B. |

Developing Your Rate-a-Prof Scale

Question 7.12

Which of the following statements would be best for evaluating how concerned a professor is about students in his or her class?

| A. |

| B. |

Finding a Sample

Now that you have developed your scale, your next step is to determine who you would like to complete your scale.

Question 7.13

To achieve the best estimate of students’ attitudes toward each professor, which of the following samples should you use?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

Finalizing Your Plan

You now have your scale to measure student attitudes toward Professor Sandman and Professor DeBestie, and you have identified what students you are going to ask to complete this scale. But there is 1 potential problem with your strategy for deciding which professor would be best to take a course with next semester—that is, something unrelated to the quality of the professor could influence students’ attitudes toward their professors. You decide to explore this possibility by asking 1 additional question of students after they have completed your scale.

Question 7.14

Which of the following questions would be best to ask in order to detect a potential bias in students’ attitudes toward the professor being rated?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Collecting Your Data

You are able to recruit 30 students who are currently enrolled in Professor Sandman’s class and 30 students who are taking a class with Professor DeBestie to complete your Rate-a-Prof Scale. You ask the students to provide the grade they expect to receive in that professor’s class. You convert the reported letter grade into the corresponding numerical value used in the calculation of GPAs (i.e., A = 4.0; A- = 3.67; B+ = 3.33, etc.).

Computing Your Rate-a-Prof Scale Attitude Score

This is an example of what your data set would look like. The top row shows the variable names, and the other rows display the data for the first 5 respondents’ ratings of Professor Sandman and the first 5 respondents’ ratings of Professor DeBestie.

| Professor | Teaching Strategies | Expectations | Enthusiasm | Fall Asleep | Responsive | Expected Grade |

| Sandman | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 3.67 |

| Sandman | 3 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 2.33 |

| Sandman | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 3.0 |

| Sandman | 2 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4.0 |

| Sandman | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 4.0 |

| DeBestie | 5 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 5 | 4.0 |

| DeBestie | 5 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 3.33 |

| DeBestie | 4 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 4.0 |

| DeBestie | 5 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 5 | 3.0 |

| DeBestie | 3 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 4.0 |

Computing Your Rate-a-Prof Scale Attitude Score

You now have student ratings for both professors on the 5 individual items. Your next step is to calculate each student’s overall evaluation of the professor based on individual ratings. Before you can do this, you need to remember that one of your items, “I frequently fall asleep in this professor’s class,” was negatively worded. This means that a low rating on this item is equivalent to a high rating on another item. Students who consider someone to be a high-quality professor will tend to agree with the other items, but will disagree with this particular statement. You will need to adjust the responses for the “frequently fall asleep” item so that agreement reflects a positive evaluation of the professor. To do this, you will use a process called reverse-coding.

Reverse-coding

Computing Your Rate-a-Prof Scale Attitude Score

In reverse-coding, you substitute a respondent’s original answer with the opposite score on the scale. That is, if a person gave a “1” to the item, the response is now changed to a “5.”

| Original response alternatives values | |||||

|

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neither Agree nor Disagree | Agree | Strongly Agree | |

| New response alternatives values after reverse-coding | |||||

| 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | |

| Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neither Agree nor Disagree | Agree | Strongly Agree | |

Computing Your Rate-a-Prof Scale Attitude Score

For each of the ratings below, provide the new value for the “fall asleep” variable after reverse-coding.

| Professor | Teaching Strategies | Expectations | Enthusiasm | Fall Asleep | Reverse-Coded Fall Asleep | Responsive | Expected Grade |

| Sandman | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 3.67 | |

| Sandman | 3 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 2.33 | |

| Sandman | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 3.0 | |

| Sandman | 2 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4.0 | |

| Sandman | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 4.0 | |

| DeBestie | 5 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 5 | 4.0 | |

| DeBestie | 5 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 3.33 | |

| DeBestie | 4 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 4.0 | |

| DeBestie | 5 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 5 | 3.0 | |

| DeBestie | 3 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 4.0 |

Question

Computing Your Rate-a-Prof Scale Attitude Score

Now that you have reverse-coded the responses to the “falling asleep” item, you are ready to calculate a student’s overall rating of the professor. Because higher scores represent more agreement with each item, you can sum all the student responses to your scale items. Your overall score can range from “5” (that is, the student strongly disagreed with every item regarding the professor’s quality) to “25” (the student strongly agreed with every item regarding the professor’s quality).

Computing Your Rate-a-Prof Scale Attitude Score

Calculate the Rate-a-Prof Attitude Score for each set of ratings.

| Professor | Teaching Strategies | Expectations | Enthusiasm | Fall Asleep (reverse-coded) | Responsive | Total Attitude Score | Expected Grade |

| Sandman | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3.67 | |

| Sandman | 3 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 2.33 | |

| Sandman | 3 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 3.0 | |

| Sandman | 2 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4.0 | |

| Sandman | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4.0 | |

| DeBestie | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4.0 | |

| DeBestie | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 3.33 | |

| DeBestie | 4 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 4.0 | |

| DeBestie | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 3.0 | |

| DeBestie | 3 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 4.0 |

Question

Computing Your Rate-a-Prof Scale Attitude Score

You now have the total Rate-a-Prof Attitude Score as well as the student’s expected grade in that professor’s class for the first 10 respondents in your study. The completed reverse-coding and calculated total scores for your Rate-a-Prof Scale are provided for you in this second data set.

You are now ready to answer the question, Who is the better professor for you to take a course with: Professor Sandman or Professor DeBestie?

Computing Your Rate-a-Prof Scale Attitude Score

This is an example of what your data set would look like. The top row shows the variable names; the other rows display the data for the first 10 participants.

| Professor | Teaching Strategies | Expectations | Enthusiasm | Fall Asleep (reverse-coded) | Responsive | Total Attitude Score | Expected Grade |

| Sandman | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 20 | 3.67 |

| Sandman | 3 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 17 | 2.33 |

| Sandman | 3 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 14 | 3.0 |

| Sandman | 2 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 15 | 4.0 |

| Sandman | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 20 | 4.0 |

| DeBestie | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 25 | 4.0 |

| DeBestie | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 23 | 3.33 |

| DeBestie | 4 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 18 | 4.0 |

| DeBestie | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 25 | 3.0 |

| DeBestie | 3 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 18 | 4.0 |

Summarizing Student Evaluations of Each Professor

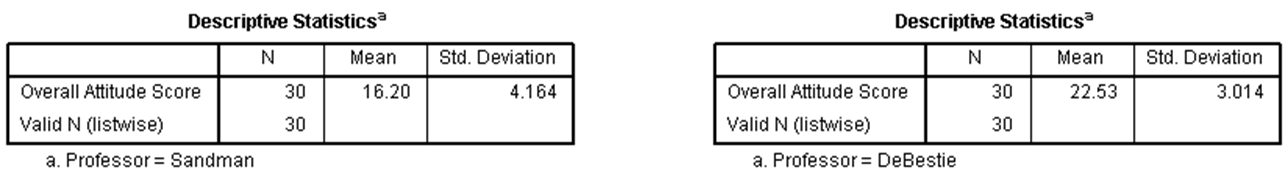

To help you make your decision, you should look at the mean Rate-a-Prof Attitude Score for each professor. This will provide you with a sense of which professor may be of high quality in the opinion of students who are currently enrolled in those professors’ classes. In addition to looking at the mean for each professor, you should also look at the variability in the overall attitude scores for each professors. If the variability is markedly lower from 1 professor to the other, then we know there is more consistency in student attitudes toward 1 professor when compared to the other professor. While you could look at the highest and lowest overall evaluation scores for each professor, the standard deviation is the best way of summarizing the variability of your scores.

Variability

Standard Deviation

Your Turn: Drawing Conclusions

Below are the mean and standard deviation for each professor:

Question 7.15

Based on these means and standard deviations, “eyeball” the data to see which professor may be the better one to take based on the attitudes of other students.

| A. |

| B. |

Your Turn: Drawing Conclusions

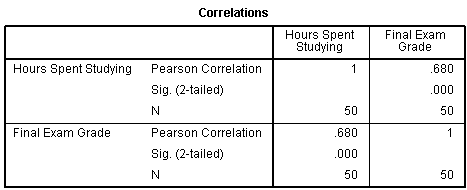

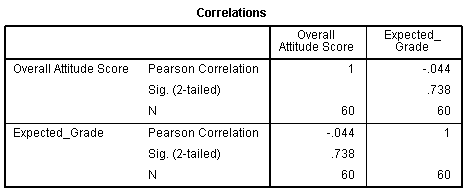

Before you decide to enroll in Professor DeBestie’s course next semester, you want to see to what extent overall attitude toward a professor based on the Rate-a-Prof Scale relates to the grade a student expects to receive in that professor’s class. If these are strongly related, then your scale might actually be measuring satisfaction with the course grade rather than opinion of the professor’s quality. To measure the degree to which 2 variables are related, you can use a correlation.

Correlation

Tutorial: Evaluating Output

The following is an example of output comparing the correlation between 2 variables. The researcher wanted to examine the relationship between number of hours spent studying and a student’s grade on a final exam.

Click on the output to learn more about each of its elements.

Question

Your Turn: Drawing Conclusions

Below is the output examining the correlation between overall attitude toward a professor and expected grade in the class.

Question 7.16

Based on this output, what can you conclude about your Rate-a-Prof Scale?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

Your Turn: Results

Question 7.17

Based on the correlation between expected grade and overall attitude toward a professor, what can you conclude?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

Take Home Message

Question 7.18

Based on your research question (“How do I best measure students’ attitudes about different professors?”), what can you conclude?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

Congratulations! You have successfully completed this activity.