1.1 The Three Criteria for Determining Psychological Disorders

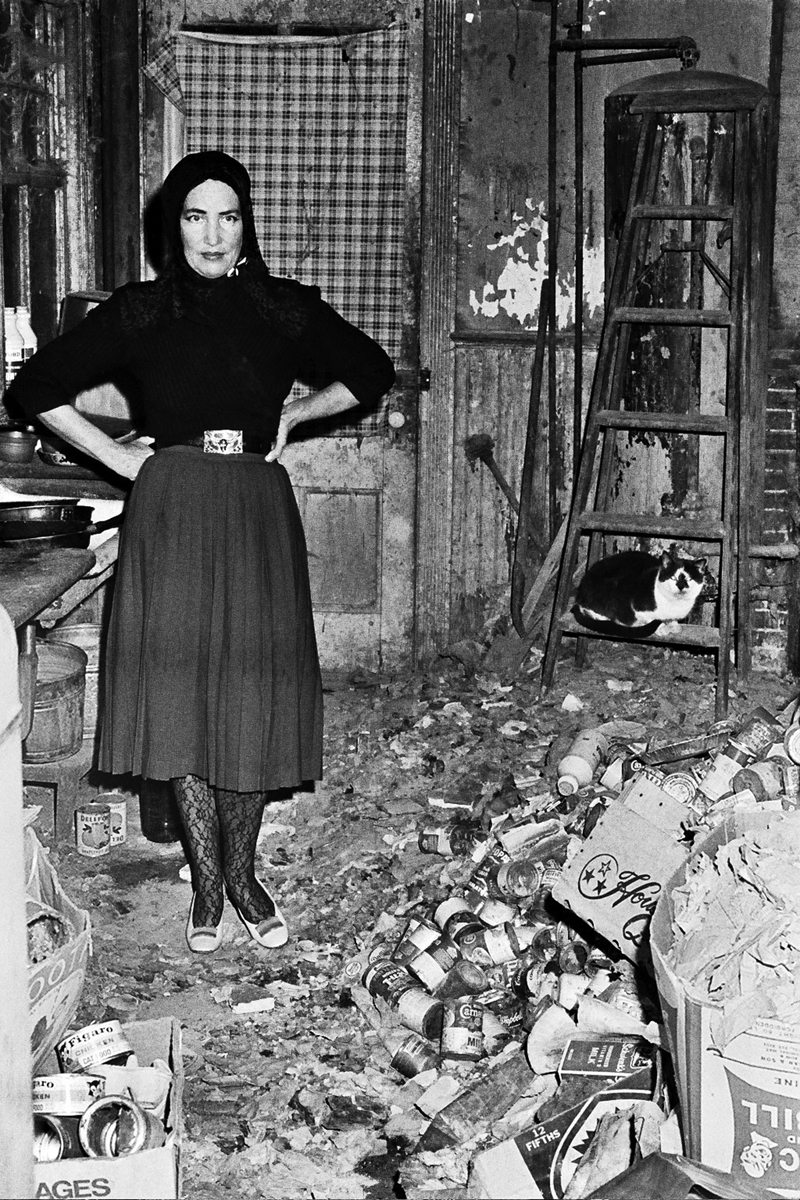

Big Edie and Little Edie came to public attention in 1971, when their unusual living situation was described in the national press. Health Department inspectors had raided their house and found the structure to be in violation of virtually every regulation. “In the dining room, they found a 5-foot mountain of empty cans; in the upstairs bedrooms, they saw human waste. The story became a national scandal. Health Department officials said they would evict the women unless the house was cleaned” (Martin, 2002). The Beales were able to remain in their house after Big Edie’s niece (Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, the former first lady) paid to have the dwelling brought up to the Health Department’s standards.

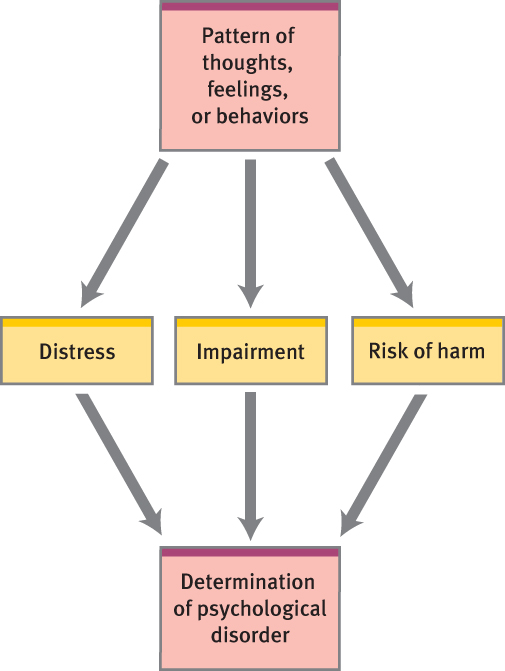

Psychological disorder A pattern of thoughts, feelings, or behaviors that causes significant personal distress, significant impairment in daily life, and/or significant risk of harm, any of which is unusual for the context and culture in which it arises.

To determine whether Big Edie or Little Edie had a psychological disorder, we must first define psychological disorder: a pattern of thoughts, feelings, or behaviors that causes significant personal distress, significant impairment in daily life, and/or significant risk of harm, any of which is unusual for the context and culture in which it arises (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Notice the word significant in the definition, which indicates that the diagnosis of psychological disorder is applied only when the symptoms have a substantial effect on a person’s life. As we shall see shortly, all three elements (distress, impairment, and risk of harm) do not need to be present; if two (or even one) of the elements are present to a severe enough degree, then the person’s condition may merit the diagnosis of a psychological disorder (see Figure 1.1). Let’s consider these three elements in more detail.

Distress

Distress can be defined as anguish or suffering, and all of us experience distress at different times in our lives. However, when a person with a psychological disorder experiences distress, it is often out of proportion to a situation. The state of being distressed, in and of itself, does not indicate a psychological disorder—it is the degree of distress or the circumstances in which the distress arises that mark abnormality. Some people with psychological disorders exhibit their distress: They may cry in front of others, share their anxieties, or vent their anger on those around them. But other people with psychological disorders contain their distress, leaving family and friends unaware of their emotional suffering. For example, a person may worry excessively but not talk about the worries, or a depressed person may cry only when alone, putting on a mask to convince others that everything is all right.

Severe distress, by itself, doesn’t necessarily indicate a psychological disorder. The opposite is also true: The absence of distress doesn’t necessarily indicate the absence of a psychological disorder. A person can have a psychological disorder without experiencing distress, although it is uncommon. For instance, someone who chronically abuses stimulant medication, such as amphetamines, may not feel distress about misusing the drug, but that person nonetheless has a psychological disorder (specifically, a type of substance use disorder).

Did either Big Edie or Little Edie exhibit distress? People who knew them describe the Beale women as free spirits, making the best of life. Like many other people, they were distressed about their financial circumstances; but they in fact had real financial difficulties, so these worries were not unfounded. Little Edie did show significant distress in other ways, though. She was angry and resentful about having to be a full-time caretaker for her mother, and the documentary film Grey Gardens (as well as the HBO film and Broadway play of the same name) clearly portrays this: When Big Edie yells for Little Edie to return to her side, Little Edie says in front of the camera, “I’ve been a subterranean prisoner here for 20 years” (Maysles & Maysles, 1976).

Although Little Edie appears to have been significantly distressed, her distress was reasonable given the situation. Being the full-time caretaker to an eccentric and demanding mother for decades would undoubtedly distress most people. Because her distress made sense in its context, it is not an element of a psychological disorder. Big Edie, in contrast, appears to have become significantly distressed when she was alone for more than a few minutes, and this response is unusual for the context. We can consider Big Edie’s distress as meeting this criterion for a psychological disorder.

Impairment in Daily Life

Psychosis An impaired ability to perceive reality to the extent that normal functioning is difficult or not possible. The two types of psychotic symptoms are hallucinations and delusions.

Hallucinations Sensations that are so vivid that the perceived objects or events seem real, although they are not. Hallucinations can occur in any of the five senses.

Delusions Persistent false beliefs that are held despite evidence that the beliefs are incorrect or exaggerate reality.

The other psychotic symptom is delusions—persistent false beliefs that are held despite evidence that the beliefs are incorrect or exaggerate reality. The content of delusions can vary across psychological disorders. Common themes include a person’s belief that:

Impairment is a significant reduction of a person’s ability to function in some important area of life. A person with a psychological disorder may be impaired in functioning at school, at work, in taking adequate care of himself or herself, or in relationships. For example, a woman’s drinking problem may interfere with her ability to do her job or to attend to her bills; a middle-aged, married man’s continually worrying about his increasing baldness—spending hours and hours each day “fixing” his hair—might impair his ability to get to work on time.

Where do mental health clinicians draw the line between normal functioning and impaired functioning? It is the degree of impairment that indicates a psychological disorder. When feeling “down” or nervous, we are all likely to function less well—for example, we may feel irritable or have difficulty concentrating. With a psychological disorder, though, the degree of impairment is atypical for the context—the person is impaired to a greater degree than most people in a similar situation. For instance, after a relationship breakup, most people go through a difficult week or two, but they still go to school or to work. They may not accomplish much, but they soon begin to bounce back. Some people, however, are more impaired after a breakup—they may not make it out of the house or even out of bed; they may not bounce back after a few weeks. These people are significantly impaired.

One type of impairment directly reflects a particular pattern of mental events: A psychosis is an impaired ability to perceive reality to the extent that normal functioning is difficult or not possible. The two forms of psychotic symptoms are hallucinations and delusions. Hallucinations are sensations that are so vivid that the perceived objects or events seem real, although they are not. Hallucinations can occur in any of the five senses, but the most common type is auditory hallucinations, in particular, hearing voices. However, a hallucination—in and of itself—does not indicate psychosis or a psychological disorder. Rather, this form of psychotic symptom must arise in a context that renders it unusual and impairs functioning.

- other people or organizations—the FBI, aliens, the neighbor across the street—are after the person (paranoid or persecutory delusions);

- his or her intimate partner is dating or interested in another person (delusional jealousy);

- he or she is more powerful, knowledgeable, or influential than is true in reality and/or that he or she is a different person, such as the president or Jesus (grandiose delusions);

- his or her body—or a part of it—is defective or functioning abnormally (somatic delusion).

Were the Beale women impaired? The fact that they lived in such squalor implies an inability to function normally in daily life. They knew about hygienic standards but didn’t live up to them. Whether the Beales were impaired is complicated by the fact that they viewed themselves as bohemians, set their own standards, and did not want to conform to mainstream values (Sheehy, personal communication, December 29, 2006). However, their withdrawal from the world can be seen as clear evidence that they were impaired. Perhaps they couldn’t function in the world and so retreated to Grey Gardens.

The women also appear to have been somewhat paranoid: In the heat of summer, they left the windows nailed shut (even on the second floor) for fear of possible intruders. The women’s social functioning was impaired to the extent that their paranoid beliefs led to strange behaviors that isolated them. In addition, their beliefs led them to behave in ways that made the house so uncomfortable—extreme temperatures and fleas—that relatives wouldn’t visit. And Big Edie’s distress at being alone for even a few minutes indicates that her ability to function independently was impaired. It seems, then, that a case could be made that both of them—Big Edie more so than Little Edie—were impaired and not functioning normally.

Risk of Harm

Some people take more risks than others. They may drive too fast or drink too much. They may diet too strenuously, exercise to an extreme, gamble away too much money, or have unprotected sex with multiple partners. For such behavior to indicate a psychological disorder, it must be outside the normal range. The criterion of danger, then, refers to symptoms of a psychological disorder that lead to life or property being put at risk, either accidentally or intentionally. For example, a person with a psychological disorder may be in danger when:

- depression and hopelessness lead him or her to attempt suicide;

- hallucinations interfere with normal safety precautions, such as checking for cars before crossing the street;

- a distorted body image and other psychological disturbances lead the person to refuse to eat enough food to maintain a healthy weight, which in turn leads to malnutrition and medical problems.

Psychological disorders can also lead people to put other people’s lives at risk. Examples of this type of danger include:

- auditory hallucinations that command the person to harm another person;

- suicide attempts that put the lives of other people at risk, such as driving a car into oncoming traffic;

- paranoia so extreme that a parent kills his or her children in order to “save” them from a greater evil.

The house in which Little Edie and Big Edie lived had clearly become dangerous. Wild animals—raccoons and rats—roamed the house, and the ceiling was falling down. But having too little money to make home repairs doesn’t mean that someone has a psychological disorder. Some might argue that perhaps the Beale women simply weren’t aware of the danger. The women were, however, aware of some dangers: When their heat stopped working, they called a heating company to repair it, and ditto for the electricity. They had a handyman come in regularly to repair fallen ceilings and walls, and to fill holes that rats might use to enter (Wright, 2007). It’s hard to say, however, whether they realized the extent to which their house itself had become dangerous.

On at least one occasion in her early 30s, Little Edie appears to have been a danger to herself. Her cousin John told someone about “a summer afternoon when he watched Little Edie climb a catalpa tree outside Grey Gardens. She took out a lighter. He begged her not to do it. She set her hair ablaze” (Sheehy, 2006). From then on, her head was at least partially bald, explaining her ever-present head covering.

Aside from Little Edie’s single episode with the lighter, it’s not clear how much the Beale women’s behavior led to a significant risk of harm. Big Edie recognized most imminent dangers and took steps to ensure her and her daughter’s safety. The women were not overtly suicidal nor did they harm others. The only aspect of their lives that suggests a significant risk of harm was the poor hygienic standards they maintained.

Context and Culture

As we noted earlier, what counts as a significant level of distress, impairment, or risk of harm depends on the context in which it arises. That human waste was found in an empty room at Grey Gardens might indicate abnormal behavior, but the fact that the plumbing was out of order for a period of time might provide a reasonable explanation. Of course, knowing that the human waste was allowed to remain in place after the plumbing was fixed would probably decide the question of whether the behavior was abnormal.

In addition, the Beales appeared to have delusions—that people wanted to break into the house or kidnap them, and that then-President Nixon might have been responsible for the 1971 “raid” on their house by the town health inspectors (Wright, 2007). But these delusions aren’t necessarily as farfetched as they might sound. Their house was broken into in 1968, and, as relatives of Jackie Kennedy, they had cars with Secret Service agents posted outside their house while John F. Kennedy was president.

Behavior that seems inappropriate in one context may make sense in another. Having a psychological disorder isn’t merely being different—we wouldn’t say that someone was abnormal simply because he or she was avant-garde or eccentric or acted on unusual social, sexual, political, religious, or other beliefs (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). And as we’ve seen with the Beales, the effects of context can blur the line between being different and having a disorder. TABLE 1.1 provides additional information about psychological disorders.

|

Culture The shared norms and values of a society that are explicitly and implicitly conveyed to its members by example and through the use of reward and punishment.

Culture, too, can play a crucial role in how mental illness is diagnosed. To psychologists, culture is the shared norms and values of a society; these norms and values are explicitly and implicitly conveyed to members of the society by example and through the use of reward and punishment. Different societies and countries have their own cultures, each with its own view of what constitutes mental health and mental illness—even what constitutes distress and how to communicate that distress. For example, in some cultures, distress may be conveyed by complaints of fatigue or tiredness rather than by sadness or depressed mood. Some sets of symptoms that are recognized as disorders in other parts of the world are not familiar to most Westerners. One example, described in Case 1.1, is koro, a disorder that arises in some people from countries in Southeast Asia. Someone with koro rapidly develops an intense fear that his penis—or her nipples and vulva—will retract into the body and possibly cause death (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). This disorder may break out in clusters of people, like an epidemic (Bartholomew, 1998; Sachdev, 1985). Similar genital-shrinking fears have been reported in India and in West African countries (Dzokoto & Adams, 2005; Mather, 2005).

CASE 1.1 • FROM THE OUTSIDE: Cultural Influence on Symptoms

Although most cases of koro appear to resolve quickly, in a minority of cases, symptoms may persist.

A 41-year-old unmarried, unemployed male from a business family, presented with the complaints of gradual retraction of penis and scrotum into the abdomen. He had frequent panic attacks, feeling that the end had come. The symptoms had persisted more than 15 years with a waxing and waning course. During exacerbations he spent most of his time measuring the penis by a scale and pulling it in order to bring it out of [his] abdomen. He tied a string around it and attached it to a hook above to prevent its shrinkage during [the] night.…He did not have regular work and was mostly dependent on the family.

(Kar, 2005, p. 34)

In addition, cultural norms about psychopathology are not set in stone but can shift. Consider that, in 1851, Dr. Samuel Cartwright of Louisiana wrote an essay in which he declared that slaves’ running away was evidence of a serious mental disorder that he called “drapetomania” (Eakin, 2000). More recently, homosexuality was officially considered a psychological disorder in the United States until 1973, when it was removed from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), the manual used by mental health clinicians to classify psychological disorders.

Let’s examine the behavior of the Beales within their context and culture. Big Edie’s father claimed that his ancestors were prominent French Catholics; she and her siblings grew up financially well off. Big Edie was a singer and a performer, but, as a product of her time, she was expected to marry well (McKenna, 2004). Her father arranged for her to wed New York lawyer Phelan Beale, from a socially prominent Southern family (Rakoff, 2002). Little Edie was born about a year later, followed by two brothers. Big Edie was very close to her daughter, even keeping her out of school when Little Edie was 11 and 12, ostensibly for “health reasons.” However, Little Edie was well enough to go to the movies with her mother every day and on a shopping trip to Paris (Sheehy, 2006).

After she was married, Big Edie continued to sing, to write songs with her accompanist, and even to record some of those songs. At that time, however, cultural conventions required a woman of Big Edie’s social standing to stop performing after marrying, even if such performances generally were limited to social functions. Big Edie’s need to perform was almost a compulsion, though, and she would head straight to the piano at family gatherings.

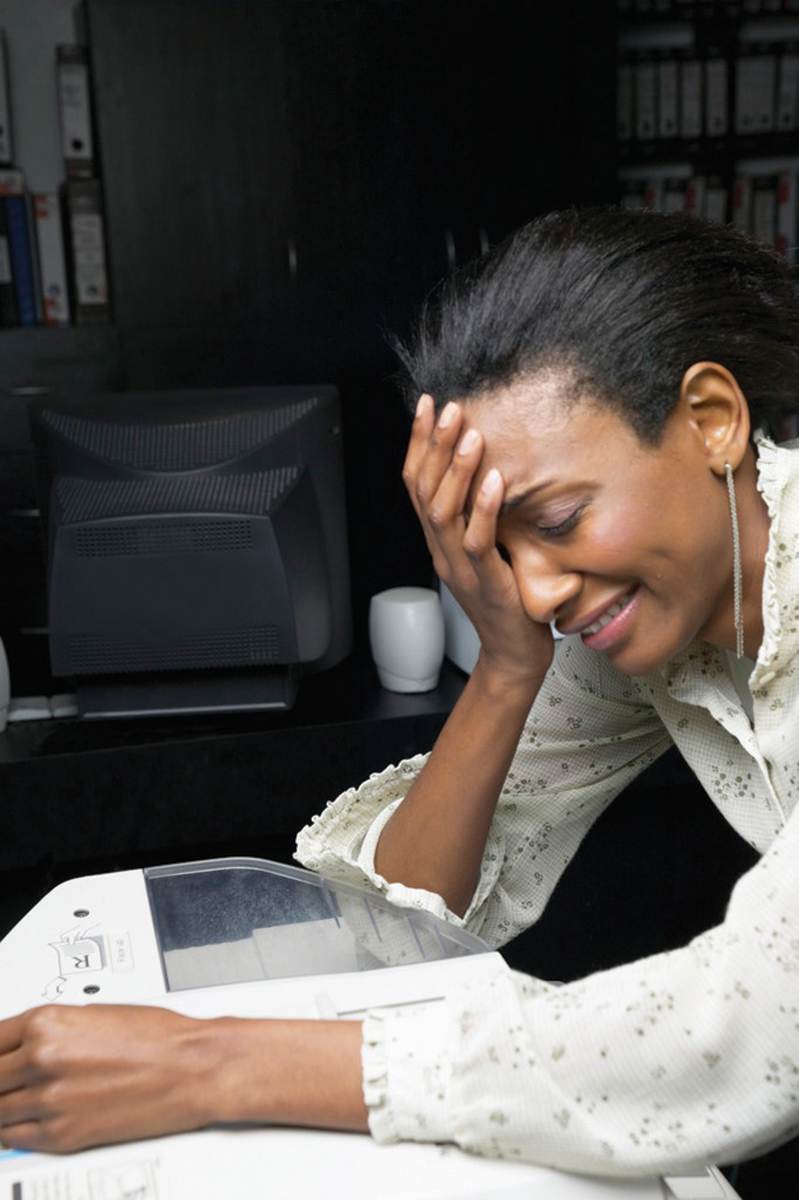

GETTING THE PICTURE

UpperCut Images/Superstock

In 1934, when Little Edie was 16, Big Edie and her husband divorced; divorce back then was much less common and much less socially acceptable than it is today. This event marked the start of Big Edie’s life as a recluse (Davis, 1969). By 1936, the house and grounds began to suffer from neglect (Davis, 1996). In 1942, Big Edie’s husband stopped supporting her financially after she showed up late for their son’s wedding, dressed inappropriately—another time when Big Edie’s behavior was unusual for the context and culture. Big Edie’s father set up a trust fund for her, which provided a small monthly allowance, barely enough to pay for food and other necessities.

Like her mother, Little Edie was artistically inclined. She aspired to be an actress, dancer, and poet. In 1946, she left home to live in New York City and work as a model, but her father disapproved of this, as he had disapproved of his wife’s musical performances (Sheehy, 2006).

In 1952, after 6 years of being separated from her daughter, Big Edie became seriously depressed (Sheehy, 2006), although there is no information about her specific symptoms. She spent 3 months calling Little Edie daily, begging her to return to Grey Gardens. Eventually, Little Edie moved back to take care of Big Edie. When she did, her artistic aspirations became only dreams and fantasies. Grey Gardens vividly captures Little Edie’s disappointment at the path her life took—becoming a round-the-clock caretaker to her mother, a disappointed woman herself.

So far, we’ve seen that psychological disorders lead to significant distress, impairment in daily life, and/or risk of harm. We’ve also seen that the determination of a disorder depends on the culture and context in which these elements occur. A case could be made that the Beale women did have psychological disorders; let’s consider each woman in turn. Big Edie exhibited significant distress when alone for more than a few minutes; her reclusiveness and general lifestyle suggest an impaired ability to function independently in the world—perhaps to the point where there might have been a risk of harm to herself or her daughter. Her behavior and experience appear to satisfy the first two criteria, which is enough to indicate that she had a psychological disorder. Moreover, Big Edie suffered from depression at some point after Little Edie moved to New York, and she experienced enough distress that she begged her daughter to return to Grey Gardens.

As for Little Edie, her distress was appropriate for the context and thus would not meet the first criterion. Her ability to function independently, though, appears to have been significantly impaired, which also increased the risk of harm to herself and her mother. It appears that she, too, suffered from a psychological disorder. However, these conclusions must be tentative—they are based solely on films of the women and other people’s descriptions and memories of them.

Now that we know what is required to determine whether someone has a psychological disorder, we’ll spend the rest of this chapter looking at how psychopathology has been explained through the ages, up to the present.

Thinking Like A Clinician

Suppose Pietro was hearing the voice of a deceased relative, and he was from a culture where such experiences were considered normal—or at least not abnormal. But he was distressed about hearing the voice, to the point where he was having a hard time doing his job. Should Pietro be considered to have a psychological disorder? If so, why? If not, why not? What additional information would you want to help you decide, if you weren’t sure?