1.2 Views of Psychological Disorders Before Science

Psychological disorders have probably been around as long as there have been humans. In every age, people have tried to answer the fundamental questions of why mental illness occurs and how to treat it. In this section, we begin at the beginning, by considering the earliest known explanations of psychological disorders.

Ancient Views of Psychopathology

Throughout history, humans have tried to understand the causes of mental illness in an effort to counter its detrimental effects. The earliest accounts of abnormal thoughts, feelings, and behaviors focused on two possible causes: (1) supernatural forces and (2) an imbalance of substances within the body.

Supernatural Forces

Societies dating as far back as the Stone Age appear to have explained psychological disorders in terms of supernatural forces—magical or spiritual in nature (Porter, 2002). Both healers and common folk believed that the mentally ill were possessed by spirits or demons, and possession was often seen as punishment for some religious, moral, or other transgression.

In the ancient societies that understood psychological disorders in this way, treatment often consisted of exorcism—a ritual or ceremony intended to force the demons to leave the person’s body and restore the person to a normal state. The healer led the exorcism, which in some cultures consisted of reciting incantations, speaking with the spirit, and inflicting physical pain to induce the spirit to leave the person’s body (Goodwin et al., 1990). This belief in supernatural forces was common in ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia and, as we shall see shortly, arose again in the Middle Ages in Europe and persists today in some cultures. Although it is tempting to regard such a view of psychopathology and its treatment as barbaric or uncivilized, the healers were simply doing the best they could in trying to understand and treat devastating impairments.

Imbalance of Substances Within the Body

Throughout history, some societies have understood psychological disorders as arising from imbalances of one or more bodily substances.

Chinese Qi

Healers in China beginning in the 7th century b.c.e. viewed psychological disorders as a form of physical illness, reflecting imbalances in the body and spirit. This view rests on the belief that all living things have a life force, called qi (pronounced “chee,” as in cheetah), which flows through the body along 12 channels to the organs. Illness results when qi is blocked or seriously imbalanced; to this day, this view underpins aspects of Chinese medicine. Even today, Chinese treatment for various problems, including some psychological disorders, aims to restore the proper balance of qi. Practitioners use a number of techniques, including acupuncture and herbal medicine.

Ancient Greeks and Romans

Like the ancient Chinese, the ancient Greeks viewed mental illness as a form of bodily illness arising from imbalances (U.S. National Library of Medicine, 2005). Specifically, mental illness arose through an imbalance of four humors (that is, bodily fluids): black bile, blood, yellow bile, and phlegm. Each humor corresponded to one of four basic elements: earth, air, fire, and water. The ancient Greeks believed that differences in character reflected the relative balance of these humors, and an extreme imbalance of the humors resulted in illness—including mental illness. Most prominent among the resulting mental disorders were mania (marked by excess uncontrollability, arising from too much of the humors blood and yellow bile) and melancholy (marked by anguish and dejection, and perhaps hallucinations, arising from too much black bile). The goal of treatment was to restore the balance of humors through diet, medicine, or surgery (such as bleeding—letting some blood drain out of the body—if the person were diagnosed as having too much of the humor blood).

Beginning with the physician Hippocrates (460–377 b.c.e.), the ancient Greeks emphasized reasoning and rationality in their explanations of natural phenomena, rejecting supernatural explanations. Hippocrates suggested that the brain—rather than any other bodily organ—is responsible for mental activity, and that mental illness arises from abnormalities in the brain (Shaffer & Lazarus, 1952). Today, the term medical model is used to refer to Hippocrates’ view that all illness, including mental illness, has its basis in biological disturbance. Galen (131–201 c.e.), a Roman doctor, extended the ideas of the Greeks. Galen proposed that imbalances in humors produced emotional imbalances—and such emotional problems in turn could lead to psychological disorders.

Forces of Evil in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance

With the rise of Christianity in Europe, psychopathology came to be attributed to forces of evil. During the Middle Ages (approximately 500–1400 c.e.), the Greek emphasis on reason and science lost influence, and madness was once again thought to result from supernatural forces. However, at this time mental illness was conceived as a consequence of a battle between good and evil for the possession of a person’s soul. Prophets and visionaries were believed to be possessed or inspired by the will of God. For example, French heroine Joan of Arc reported that she heard the voice of God command her to lead a French army to drive the British out of France. The French hailed her as a visionary. In contrast, other men and women who reported such experiences usually were believed to be possessed by the devil or were viewed as being punished for their sins. Treatment consisted of attempts to end the possession: exorcism, torture (with the idea that physical pain would drive out the evil forces), starvation, and other forms of punishment to the body. Such inhumane treatment was not undertaken everywhere, though. As early as the 10th century, Islamic institutions were caring humanely for those with mental illness (Sarró, 1956).

During the Renaissance (approximately the 1400s through the 1600s), mental illness continued to be viewed as a result of demonic possession, and witches were held responsible for a wide variety of ills. Indeed, witches were blamed for other people’s physical problems and even for societal and environmental problems, such as droughts or crop failures. As before, treatment was primarily focused on ridding the person of demonic forces, in one way or another.

During this period, people believed that witches put the whole community in jeopardy through their evil acts and through their association with the devil (White, 1948). The era is notable for its witch hunts, which were organized efforts to track down people who were believed to be in league with the devil and to have inflicted possession on other people (Kemp, 2000). Once found, these “witches” were often burned alive. The practice of witch burning spread throughout Europe and the American colonies:

Judges were called upon to pass sentence on witches in great numbers. A French judge boasted that he had burned 800 women in 16 years on the bench; 600 were burned during the administration of a bishop in Bamberg. The Inquisition, originally started by the Church of Rome, was carried along by Protestant Churches in Great Britain and Germany. In Protestant Geneva 500 persons were burned in the year 1515. Other countries, where there were Catholic jurists, boasted of as many burnings. In Treves, 7,000 were reported burned during a period of several years.

(Bromberg, 1937, p. 61, quoted in White, 1948, p. 8)

Rationality and Reason in the 18th and 19th Centuries

At the end of the Renaissance, rational thought and reason gained acceptance again. French philosopher René Descartes proposed that mind and body are distinct and that bodily illness arises from abnormalities in the body, whereas mental illness arises from abnormalities in the mind. Similarly, according to the 17th-century British philosopher John Locke, insanity is caused by irrational thinking, and so could be treated by helping people regain their rational, logical thought process.

However, the theory that deficits in rationality and reason caused mental illness did not lead to consistent approaches to treatment. In the Western world, the mentally ill were treated differently from country to country and decade to decade. As we see in the following sections, various approaches were tried in an effort to cope with the mentally ill and with mental illness itself.

Asylums

Asylums Institutions to house and care for people who are afflicted with mental illness.

The Renaissance was a time of widespread innovation and enlightened thinking. For some people, this enlightenment extended to their view of how to treat those with mental illness—humanely. Some groups founded asylums, institutions to house and care for people who were afflicted with mental illness. In general, asylums were founded by religious orders; the first of this type was opened in Valencia, Spain, in 1409 (Sarró, 1956). In subsequent decades, asylums for the mentally ill were built throughout Europe.

Before long, though, criminals and others who weren’t necessarily mentally ill were sent to asylums, and the facilities became overcrowded. Their residents were then more like inmates than patients. At least in some cases, people were sent to asylums simply to keep them off the street, without any effort to treat them.

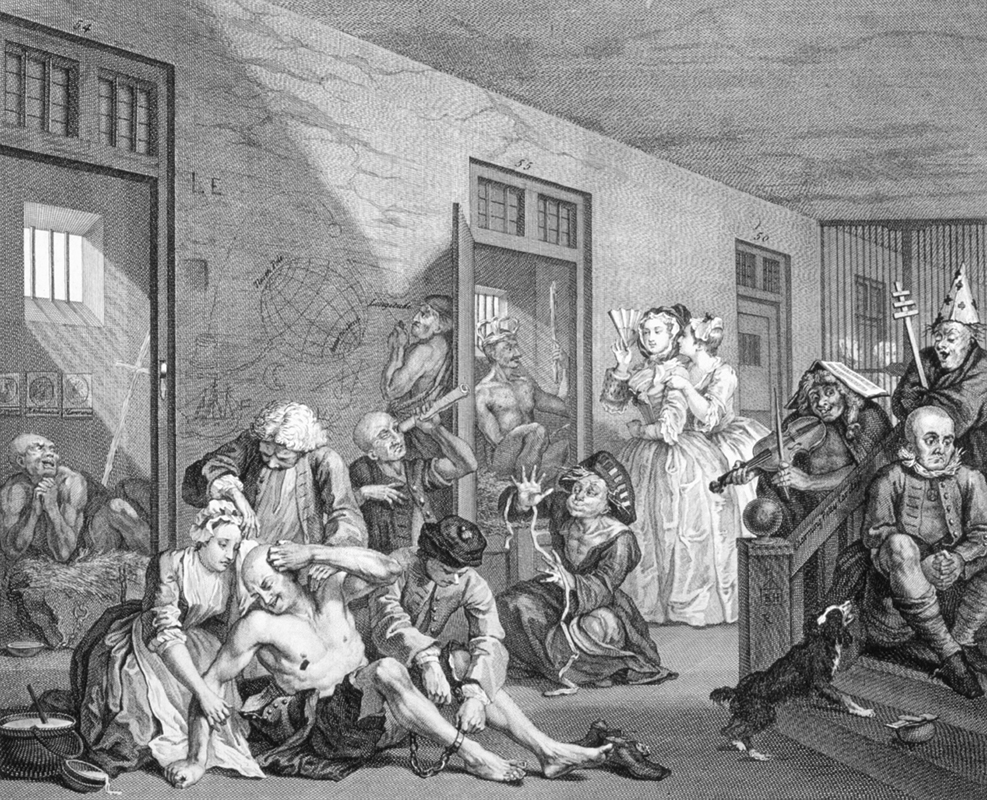

Perhaps the most famous asylum from this era was the Hospital of St. Mary of Bethlehem in London (commonly referred to as “Bedlam,” which became a word meaning “confusion and uproar”). In 1547, that institution shifted from being a general hospital to an asylum used to incarcerate the mad, particularly those who were poor. Residents were chained to the walls or floor or put in cages and displayed to a paying public, much like animals in a zoo (Sarró, 1956). Officials believed that such exhibitions would deter people from indulging in behaviors believed to lead to mental illness.

Pinel and Mental Treatment

The humane treatment of people with psychological disorders found a great supporter in French physician Phillipe Pinel (1745–1826). He and others transformed the lives of asylum patients at the Salpêtrière and Bicêtre Hospitals (for women and men, respectively) in Paris: In 1793, Pinel removed their chains and stopped “treatments” that involved bleeding, starvation, and physical punishment (Porter, 2002). Pinel and his colleagues believed that “madness” is a disease; they carefully observed patients and distinguished between different types of “madness.” Pinel also identified partial insanity, where the person was irrational with regard to one topic but was otherwise rational. He believed that such a person could be treated through psychological means, such as reasoning with him or her, which was one of the first mental treatments for mental disorders.

Moral Treatment

Moral treatment Treatment of the mentally ill that involved providing an environment in which people with mental illness were treated with kindness and respect and functioned as part of a community.

In the 1790s, a group of Quakers in England developed a treatment for mental illness that was based on their personal and religious belief systems. Mental illness was seen as a temporary state during which the person was deprived of his or her reason. Moral treatment consisted of providing an environment in which people with mental illness were treated with kindness and respect. The “mad” residents lived out in the country, worked, prayed, rested, and functioned as a community. Over 90% of the residents treated this way for a year recovered (Whitaker, 2002), at least temporarily.

Moral treatment also began to be used in the United States. Around the time that Pinel was unchaining the mentally ill in France, Doctor Benjamin Rush (1745–1813), a physician at the Pennsylvania Hospital in Philadelphia, moved the mentally ill from filthy basement cells to rooms above ground level, provided them with mattresses and meals, and treated them with respect.

In the 1840s Dorothea Dix (1802–1887), a schoolteacher who had witnessed the terrible conditions in the asylums of New England, also began to support moral treatment. She engaged in lifelong humanitarian efforts to ensure that the mentally ill were housed separately from criminals and treated humanely, in both public and private asylums (Viney, 2000). Dix also helped to raise millions of dollars for building new mental health facilities throughout the United States. Her work is all the more remarkable because she undertook it at a time when women did not typically participate in such social projects.

Moral treatment proved popular, and its success had an unintended consequence: Unlike private asylums, public asylums couldn’t turn away patients, and thus their population increased tenfold, as the mentally ill were joined by people with epilepsy and others with neurological disorders, as well as many who might otherwise have gone to jail. As a result, public institutions housing the mentally ill again became overcrowded and underfunded, and moral treatment—or treatments of any kind—were no longer provided (Porter, 2002). Sedation and management became the new goals.

Thinking Like A Clinician

Why might explanations of mental illness as arising from supernatural forces have been popular for so long? How does a given treatment follow from beliefs about the cause of mental illness? Can you think of at least two specific examples where beliefs about the cause of mental illness have shaped treatments in different ways?