1.4 Scientific Accounts of Psychological Disorders

In the early 20th century, advances in science led to an interest in theories of psychological disorders that could be tested rigorously, generating hypotheses that could be proven or disproven. Several different scientific approaches (and accompanying theories) that emerged at that time are still with us today; they focus on different aspects of psychopathology, including behavior, cognition, social interactions, and biology. These scientific accounts and theories have thrived because studies have shown that they explain some aspects of mental illness. Let’s examine these modern approaches to psychopathology and how they could explain Big Edie and Little Edie’s thoughts, feelings, and behavior.

Behaviorism

Behaviorism An approach to psychology that focuses on understanding directly observable behaviors in order to understand mental illness and other psychological phenomena.

All of the views discussed so far focus on forces that affect mental processes and mental contents. However, some psychologists in the early 20th century took a radically different perspective and focused only on directly observable behaviors. Spearheaded by American psychologists Edward Lee Thorndike (1874–1949), John B. Watson (1878–1958), and Clark L. Hull (1884–1952), and, most famously, B. F. Skinner (1904–1990), behaviorism focuses on understanding directly observable behaviors rather than unobservable mental processes and mental contents (Watson, 1931). The behaviorists’ major contribution to understanding psychopathology was to propose scientifically testable mechanisms that may explain how maladaptive behavior arises (Skinner, 1986, 1987). These psychologists focused their research on the association between factors that trigger a behavior and on a behavior and its consequences; the consequences influence whether a behavior is likely to recur. For instance, to the extent that using a drug has pleasurable consequences, a person is more likely to use the drug again.

At about the same time in Russia, Nobel Prize–winning physiologist Ivan Pavlov (1849–1936) accidentally discovered an association between a reflexive behavior and the conditions that occur immediately prior to it (that is, its antecedents), an association created by a process sometimes referred to as Pavlovian conditioning (Pavlov, 1936). He studied salivation in dogs, and he noticed that dogs increased their salivation both while they were eating (which he predicted—the increased salivation when eating is a reflexive behavior) and right before they were fed (which he did not predict). He soon determined that the dogs began salivating when they heard the approaching footsteps of the person feeding them. The feeder’s footsteps (a neutral stimulus) became associated with the stimulus of food in the mouth, thus leading the dogs to salivate when hearing the sound of footsteps; the dogs’ past association between the feeder’s footsteps and subsequent food led to a behavior change.

Pavlov investigated the reflexive behavior of salivation, and other researchers have found that reflexive fear-related behaviors (such as a startle response) can be conditioned in the same fashion. These findings contributed to the understanding of how the severe fears and anxieties that are part of many psychological disorders can arise—how neutral stimuli that have in the past been paired with fear-inducing objects or events can, by themselves, come to induce fear or anxiety. We will consider such conditioning in more detail in Chapter 2.

Among the most important insights of behaviorism, then, is that a person’s behavior, including maladaptive behavior, can result from learning—from a previous association with an object, situation, or event. Big Edie appears to have developed maladaptive behaviors related to a fear of being alone. This may have been a result of past negative experiences with (and the resulting associations to) being alone, perhaps by neighborhood boys playing tricks on her when they knew she was home alone.

Behaviorism ushered in new explanations of—and treatments for—some psychological disorders. The behaviorists’ emphasis on controlled, objective observation and on the importance of the situation had a deep and lasting impact on the field of psychopathology. However, researchers also learned that not all psychological problems could readily be explained as a result of maladaptive learning. Rather, mental processes and mental contents are clearly involved in the development and maintenance of many psychological disorders. This opened the door for cognitive psychology.

The Cognitive Contribution

Psychodynamic and behaviorist explanations of psychological disorders seemed incompatible. Psychodynamic theory emphasized private mental processes and mental contents; behaviorist theories emphasized directly observable behavior. Then, the late 1950s and early 1960s saw the rise of cognitive psychology, the area of psychology that studies mental processes and contents starting from the analogy of information processing by a computer. Researchers developed new, behaviorally based methods to track the course of hidden mental processes and characterize the nature of mental contents, which began to be demystified. If a mental process operates on mental contents like a computer program operates on stored data, direct connections can be made between observable behavior, as well as personal experiences, and mental events.

Cognitive psychology has contributed to the understanding of psychological disorders by focusing on specific changes in mental processes and mental contents. For instance, people with anxiety disorders—a category of disorders that involves extreme fear, panic, and/or avoidance of a feared stimulus—tend to focus their attention in particular ways, creating a bias in what they expect and remember. In turn, these biased memories appear to support the “truth” of their inaccurate view about the danger of the stimulus that elicits their fear. For instance, a man who is very anxious in social situations may pay excessive attention to whether other people seem to be looking at him; when people glance in his general direction, he will then notice the direction of their gaze and infer that they are looking at him. Later, he will remember that “everyone” was watching him.

Other cognitive explanations of psychological disorders focused on distortions in the content of people’s thoughts. Psychiatrist Aaron Beck (b. 1921) and psychologist Albert Ellis (1913–2007) each focused on how people’s irrational and inaccurate thoughts about themselves and the world can contribute to psychological disorders (Beck, 1967; Ellis & MacLaren, 1998). For example, people who are depressed often think very negatively and inaccurately about themselves, the future, and the world. They often believe that no one will care about them; or, if someone does care, this person will leave as soon as he or she sees how really inept, ugly, or unlovable the depressed person is. Such thoughts could make anyone depressed! For cognitive therapists, treatment involves shifting, or restructuring, people’s faulty beliefs and irrational thoughts that led to psychological disorders.

Cognitive therapy might have been appropriate for the Beale women, who had unusual beliefs. Consider the fact that Little Edie worried about leaving her mother alone in her room for more than a few minutes because she might come back and find her mother dead (Graham, 1976). Big Edie also had unusual beliefs. One time, a big kite was hovering over Grey Gardens and she called the police, concerned that the kite was a listening device or a bomb (Wright, 2007).

The focus on particular mental processes and mental contents illuminates some aspects of psychological disorders. But just as behaviorist theories do not fully address why people develop the particular beliefs and attitudes they have, cognitive theories do not fully explain why a person’s mental processes and contents are biased in a particular way. Knowledge about social and neurological factors (i.e., factors that affect the brain and its functioning) helps to complete the picture.

Social Forces

We can view behavioral and cognitive explanations as psychological: Both refer to thoughts, feelings, or behaviors of individual people. In addition to these sorts of factors, we must also consider social factors, which involve more than a single person. There is no unified social explanation for psychological disorders, but various researchers and theorists in the last half of the 20th century recognized that social forces affect the emergence and maintenance of mental illness. Many of these social forces, such as the loss of a relationship, abuse, trauma, neglect, poverty, and discrimination, produce high levels of stress.

One of the social factors that occurs earliest in life is attachment style, which characterizes the particular way a person relates to intimate others, and it begins in infancy. Researchers have delineated four types of attachment styles in children:

- Secure attachment. Those who become upset when their mother leaves but quickly calm down upon her return (Ainsworth & Bell, 1970).

- Resistant/anxious attachment. Those who become angry when their mother leaves and remain angry upon her return, sometimes even hitting her (Ainsworth & Bell, 1970).

- Avoidant attachment. Those who had no change in their emotions based on mother’s presence or absence (Ainsworth & Bell, 1970).

- Disorganized attachment. Those who exhibit a combination of resistant and avoidant styles and also appear confused or fearful with their mother (Main & Solomon, 1986).

GETTING THE PICTURE

©ONOKY –Photononstop/Alamy

Among American children, those with an insecure attachment style (the last three styles listed above) are more likely to develop symptoms of psychological disorders (Main & Solomon, 1986; Minde, 2003).

Research on social factors also points to the ways that relationships—and the social support they provide—can buffer the effects of negative life events (-Hyman et al., 2003; Swift & Wright, 2000). For example, researchers have found that healthy relationships can mitigate the effects of a variety of negative events, such as abuse (during childhood or adulthood), trauma, discrimination, and financial hardship. The opposite is also true: The absence of protective relationships increases a person’s risk for developing a psychological disorder in the face of a significant stressor (Dikel et al., 2005). (Note that stressor is the technical term used to refer to any stimulus that induces stress.)

The Beale women experienced many stressors: financial problems, the dissolution of Big Edie’s marriage, and, in later years, social isolation. Their extended family and their community ostracized them, at least in part because they were independent-minded and artistic women. In addition, Little Edie endured her own unique social stresses: Both her parents were excessively controlling. Her father restricted her artistic pursuits, and Little Edie could scarcely leave her mother’s room before her mother was calling urgently for her to return; this intense attachment and close physical proximity echo their relationship when Little Edie was a child.

Like the other factors, social factors do not fully account for how and why psychological disorders arise. For instance, social explanations cannot tell us why, of people who experience the same circumstances, some will go on to develop a psychological disorder and others won’t.

Biological Explanations

In 1913 it was discovered that one type of mental illness—which was then called general paresis, or paralytic dementia—was caused by a sexually transmitted disease, syphilis. The final stage of this disease damages the brain and leads to abrupt changes in mental processes, including psychotic symptoms (Hayden, 2003). The discovery of a causal link between syphilis and general paresis heralded a resurgence of the medical model, the view that psychological disorders have underlying biological causes. According to the medical model, once the biological causes are identified, appropriate medical treatments can be developed, such as medications. In fact, antibiotics that treat syphilis also prevent the related mental illness, which was dramatic support for applying the medical model to at least some psychological disorders.

Since that discovery, scientists have examined genes, neurotransmitters (chemicals that allow brain cells to communicate with each other), and abnormalities in brain structure and function associated with mental illness.

What biological factors might have contributed to the Beales’ unusual lifestyle and beliefs? Unfortunately, the documentaries and biographies about the two women have not addressed this issue, so there is no way to know. All we know is that one of Big Edie’s brothers was a serious gambler, another died as a result of a drinking problem, and one of her nieces also battled problems with alcohol; taken together, these observations might suggest a family history of impulse control problems. We might be tempted to infer that such tendencies in this family reflect an underlying genetic predisposition, but we must be careful: Families share more than their genes, and common components of the environment can also contribute to psychological disorders.

In fact, this is where the medical model reveals its limitations. Explaining psychological disorders simply on the basis of biological factors ultimately strips mental disorders of the broader context in which they occur—in thinking people who live in families and societies—and provides a false impression that mental disorders arise from biological factors alone (Angell, 2011). As we shall see throughout this book, multiple factors usually contribute to a psychological disorder, and treatments targeting only biological factors usually are not the most effective. In the next section we discuss in greater detail this multiple-perspective approach and the model we will use throughout this text.

The Modern Synthesis of Explanations of Psychopathology

In the past several decades, researchers and clinicians have increasingly recognized that psychological disorders cannot be fully explained by any single type of factor or theory. Two approaches to psychopathology integrate multiple factors: the diathesis–stress model and the biopsychosocial approach.

The Diathesis–Stress Model

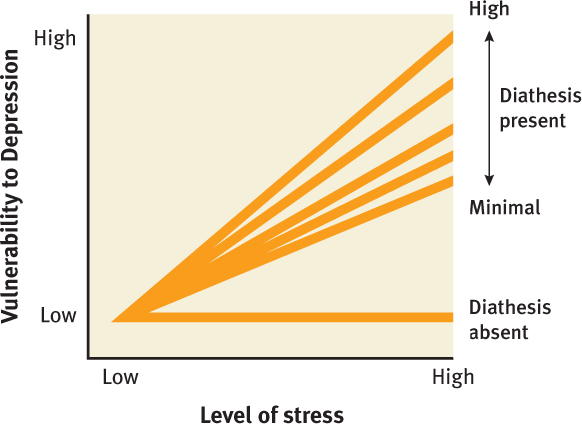

Diathesis–stress model A model that rests on the idea that a psychological disorder is triggered when a person with a predisposition—a diathesis—for the particular disorder experiences an environmental event that causes significant stress.

The diathesis–stress model is one way to bring together the various explanations of how psychological disorders arise. The diathesis–stress model rests on the claim that a psychological disorder is triggered when a person with a predisposition—a diathesis—for the particular disorder experiences an environmental event that causes significant stress (Meehl, 1962; Monroe & Simons, 1991; Rende & Plomin, 1992). Essentially, the idea is that if a person has a predisposition to a psychological disorder, a particular type of stress may trigger its occurrence. But the same stress would not have that effect for a person who did not have the predisposition; also, a person who did have a diathesis for a psychological disorder would be fine if he or she could avoid those types of high-stress events. Both factors are required.

For example, the diathesis–stress model explains why, if one identical twin develops depression, the co-twin (the other twin of the pair) also develops depression in less than one quarter of the cases (Lyons et al., 1998). Because identical twins share virtually 100% of their genes, a co-twin should be guaranteed to develop the disorder if genes alone cause it. But even identical twins experience different types and levels of stress. Their genes may be virtually identical, but their environments are not; thus, both twins do not necessarily develop the psychological disorder over time. The diathesis–stress model is illustrated in Figure 1.3.

A diathesis may be a biological factor, such as a genetic vulnerability to a disorder, or it may be a psychological factor, such as a cognitive vulnerability to a disorder, as can occur when irrational or inaccurate negative thoughts about oneself contribute to depression. The stress is often a social factor, which can be acute, such as being the victim of a crime, or less intense but chronic, such as recurring spousal abuse, poverty, or overwork. It is important to note that not everybody experiences the same social factor in the same way. And what’s important is not simply the objective circumstance—it’s how a person perceives it. For example, think about roller coasters: For one person, they are great fun; for another, they are terrifying. Similarly, Big Edie and Little Edie didn’t appear to mind their isolation and strange lifestyle and may even have enjoyed it; other people, however, might find living in such circumstances extremely stressful and depressing. Whether because of learning, biology, or an interaction between them, some people are more likely to perceive particular events and stimuli as stressors (and therefore to experience more stress) than others. The diathesis–stress model was the first approach that integrated existing, but separate, explanations for psychological disorders.

The Biopsychosocial and Neuropsychosocial Approaches

To understand the bases of both diatheses and stress, we need to look more carefully at the factors that underlie psychological disorders.

Three Types of Factors

Biopsychosocial approach The view that a psychological disorder arises from the combined influences of three types of factors—biological, psychological, and social.

Historically, researchers and clinicians grouped the factors that give rise to psychological disorders into three general types: biological (including genetics, the structure and function of the brain, and the function of other bodily systems); psychological (thoughts, feelings, and behaviors); and, social (social interactions and the environment in which they occur). The biopsychosocial approach to understanding psychological disorders rests on identifying these three types of factors and documenting the ways in which each of them contributes to a disorder.

The biopsychosocial approach leads researchers and clinicians to look for ways in which the three types of factors contribute to both the diathesis (the predisposition) and the stress. For instance, having certain genes (a biological factor), having biases to perceive certain situations as stressful (a psychological factor), and living in poverty (a social factor) all can contribute to a diathesis; similarly, chronic lack of sleep (a biological factor), feeling that one’s job is overwhelming (a psychological factor), or having a spouse who is abusive (a social factor) can contribute to stress.

However, two problems with the traditional biopsychosocial approach have become clear. First, the approach does not specifically focus on the organ that is responsible for cognition and emotion, that allows us to learn, that guides behavior, and that underlies all conscious experience—namely, the brain. The brain not only gives rise to thoughts, feelings, and behaviors, but also mediates all other biological factors; it both registers events in the body and affects bodily events.

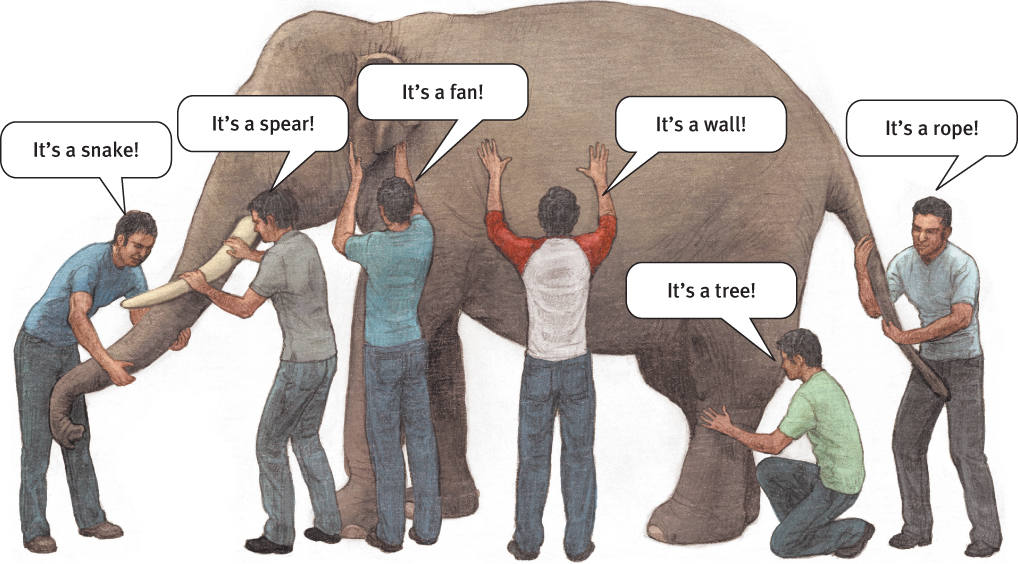

Second, in the biopsychosocial approach, the factors were often considered in isolation, as if they were items on a list. Considering the factors in isolation is reminiscent of the classic South Asian tale about a group of blind men feeling different parts of an elephant, each trying to determine what object the animal is. One person feels the trunk, another the legs, another the tusks, and so on, and each reaches a different conclusion. Even if you combined all the people’s separate reports, you might miss the big picture of what an elephant is: That is, an elephant is more than a sum of its body parts; the parts come together to make a dynamic and wondrous creature.

Researchers are beginning to understand how the three types of factors combine and affect each other. That is, factors that researchers previously considered to be independent are now known to influence each other. For example, the way that parents treat their infant was historically considered to be exclusively a social factor—the infant was a receptacle for the caregiver’s style of parenting. However, more recent research has revealed that parenting style is in fact a complex set of interactions between caregiver and infant. Consider that if the infant frequently fusses, this will elicit a different pattern of responses from the caregiver than if the infant frequently smiles; if the infant is fussy and “difficult,” the caregiver might handle him or her with less patience and warmth than if the infant seems happy and easygoing. And the way the caregiver handles the infant in turn affects how the infant responds to the caregiver. These early interactions between child and caregiver (a social factor) then contribute to a particular attachment style, which is associated with particular biases in paying attention to and perceiving emotional expressions in faces (psychological factors; Fraley & Shaver, 1997; Maier et al., 2005).

In fact, some researchers who championed the biopsychosocial approach acknowledged that explanations of psychological disorders depend on the interactions of biological, psychological, and social factors (Engel, 1977, 1980). But these researchers did not have the benefit of the recent advances in understanding the brain, and hence were not able to specify the nature of such interactions in much detail.

These problems led to a revision of the traditional biopsychosocial approach, to align it better with recent discoveries about the brain and how psychological and social factors affect brain function. We call this updated version of the classic approach the neuropsychosocial approach, which is explained in the following section.

The Neuropsychosocial Approach: Refining the Biopsychosocial Approach

The neuropsychosocial approach has two defining features: the way it characterizes the factors and the way it characterizes their interactions. As we discuss below, this approach emphasizes the brain rather than the body (hence the neuro- in its name) and maintains that no factor can be considered in isolation.

Emphasis on the Brain Rather Than the Body in General As psychologists and other scientists have learned more about the biological factors that contribute to psychological disorders, the primacy of the role of the brain—and even particular brain structures and functions—in contributing to psychological disorders has become evident. Ultimately, even such disparate biological factors as genes and bodily responses (e.g., the increased heart rate associated with anxiety) are best understood in terms of their relationship with the brain. Because of the importance of the brain’s influence on all biological functioning involved in psychological disorders, this book generally uses the term neurological rather than biological and the term neuropsychosocial rather than biopsychosocial to refer to the three types of factors that contribute to psychological disorders.

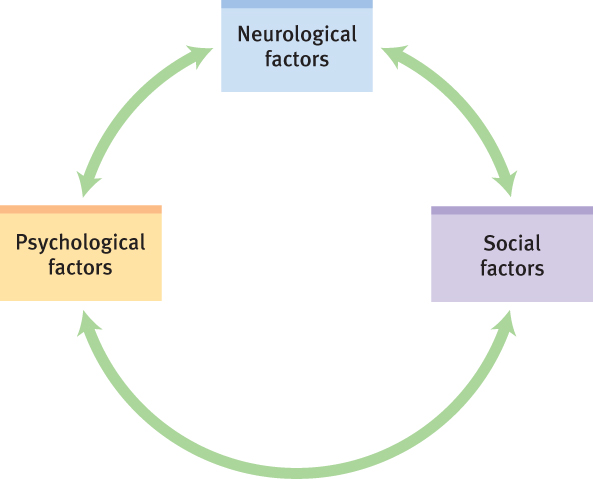

Emphasis on Feedback Loops Neurological, psychological, and social factors are usually involved simultaneously and are constantly interacting (see Figure 1.4). These interactions occur through feedback loops: Each factor is affected by the others and also feeds back to affect the other factors. Hence, no one factor can be understood in isolation, without considering the other factors. For example, problems in relationships (social factor) can lead people to experience stress (psychological factor); in turn, when people feel stressed, their brains cause their bodies to respond with a cascade of events. As you will see throughout this book, interactions among neurological, psychological, and social factors are common.

Neuropsychosocial approach The view that a psychological disorder arises from the combined influences of neurological, psychological, and social factors—which affect and are affected by one another through feedback loops.

In short, the neuropsychosocial approach can allow us to understand how neurological, psychological, and social factors—which affect and are affected by one another through feedback loops—underlie psychological disorders (Kendler, 2008).

In the next chapter, we will discuss the neuropsychosocial approach to psychological disorders in more detail, examining neurological, psychological, and social factors as well as the feedback loops among them. In that chapter, we will also continue our evaluation of the Beales and the specific factors that might contribute to their unusual behavior. In subsequent chapters, we will consider the stories of various other people.

Thinking Like A Clinician

Imagine that you are a clinician, and Natasha comes to see you about her depression. She tells you that she had a “chemical imbalance” a few years ago, which led her to be depressed then. Based on what you have read, which of the various modern perspectives was she adopting? What other types of causes could she have used to explain her depression? How would the two integrationist approaches (diathesis–stress and neuropsychosocial) explain Natasha’s depression? (Hint: Use Figures 1.3 and 1.4 to guide your answers.) What do the two approaches have in common, and in what ways do they differ from each other?