3.1 Diagnosing Psychological Disorders

Rose Mary and Rex Walls created an endurance contest for their growing children. A typical example was when Lori was diagnosed by the school nurse as severely nearsighted and in need of glasses. Rose Mary didn’t approve of eyeglasses, commenting, “If you had weak eyes…they needed exercise to get strong” (Walls, 2005. Rose Mary thought that glasses were like crutches.

Rex had unusual beliefs as well. He told his family that he couldn’t find a job in a coal mining town because the mines were controlled by the unions, which were controlled by the mob. He said he was nationally blackballed by the electricians’ union in Arizona (where he had previously worked), and in order to get a job in the mines, he must help reform the United Mine Workers of America. He claimed that he spent his days investigating that union.

Unusual beliefs may not have been the only factor that motivated Rose Mary and Rex’s behavior; they also seemed to have a kind of “tunnel vision” that led them to pay attention to their own needs and desires while being indifferent to those of their children. When Jeannette was 5 and the family was again moving, her parents rented a U-Haul truck and placed all four children (including the youngest, Maureen, who was then an infant) and some of the family’s furniture in the dark, airless, windowless back of the truck for the 14 hours it would take to get to their next “home.” Rex and Rose Mary instructed the children to remain quiet in this crypt—which was also without food, water, or toilet facilities—for the entire journey. The parents also expected the children to keep baby Maureen silent so that police wouldn’t discover the children in the back: It was illegal to transport people in the trailer. What explanation did the parents give their children for locking them up this way? They said that only two people could fit in the front of the truck.

In order to determine whether Rex and Rose Mary Walls had psychological disorders, we would have to compare their behavior and psychological functioning to some standard of normalcy. A diagnostic classification system provides a means of making such comparisons. Let’s first examine general issues about classification systems and diagnosis and then consider the system that is now most commonly used—the system described in the most recent edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.

Why Diagnose?

You may have heard that categorizing people is bad: It pigeonholes them and strips them of their individuality—right? Not necessarily. By categorizing psychological disorders, clinicians and researchers can know more about a patient’s symptoms and about how to treat the patient. To be specific, classification systems of mental disorders provide the following benefits:

- They provide a type of shorthand, which enables clinicians and researchers to use a small number of words instead of lengthy descriptions.

- They allow clinicians and researchers to group certain abnormal thoughts, feelings, and behaviors into unique constellations.

Without a classification system for psychological disorders, the problems that Pete Wentz, Jessica Alba, and Keith Urban appear to have suffered from—bipolar disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and substance abuse, respectively—would be nameless. Among other purposes, a classification system allows clinicians to diagnose and treat symptoms more effectively, allows patients to know that they are not alone in their experiences, and helps researchers to investigate the factors that contribute to psychological disorders and to evaluate treatments.Gregg DeGuire/WireImage/Getty Images

Without a classification system for psychological disorders, the problems that Pete Wentz, Jessica Alba, and Keith Urban appear to have suffered from—bipolar disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and substance abuse, respectively—would be nameless. Among other purposes, a classification system allows clinicians to diagnose and treat symptoms more effectively, allows patients to know that they are not alone in their experiences, and helps researchers to investigate the factors that contribute to psychological disorders and to evaluate treatments.Gregg DeGuire/WireImage/Getty Images

Alpha/Landov

Terry Wyatt/UPI/Landov - A particular diagnosis may convey information—useful for both clinicians and researchers—about the etiology of the disorder, its course, and indications for its treatment.

- A diagnosis can indicate that an individual is in need of attention (including treatment), support, or benefits.

- Some people find great relief in learning that they are not alone in having particular problems (see Case 3.1).

CASE 3.1 • FROM THE OUTSIDE: On Being Diagnosed with a Disorder

Sally, an articulate and dynamic 46-year-old woman, came to share her experiences with our psychiatry class. For much of her adult life, she had suffered from insomnia, panic attacks, and intense fear. Then, six years ago, a nightmare triggered memories of childhood sexual abuse and she was finally diagnosed with posttraumatic stress disorder.

Being diagnosed, she told us, was an intense relief.

“All those years, I thought I was just crazy,” she said. “My whole family used to call me the crazy one. Once, my brother called my mom and asked, ‘So, how’s my crazy sister?’ But all of a sudden I wasn’t crazy any more. It had a name. It had a real reason. I could finally understand why I felt the way I did,’ she said.”

(Rothman, 1995)

A Cautionary Note About Diagnosis

Having a classification system for mental illness has many advantages, but assigning the appropriate diagnosis can be challenging. For example, clinicians may be biased to make—or not make—particular diagnoses for certain groups of people. Patients, once diagnosed with a disorder, may be stigmatized because of it (Ben-Zeev et al., 2010). In what follows, we examine the possibilities of bias and stigma in more detail.

Diagnostic bias A systematic error in diagnosis.

A diagnostic bias is a systematic error in diagnosis (Meehl, 1960). Such a bias can cause groups of people to receive a particular diagnosis disproportionately, on the basis of an unrelated factor such as sex, race, or age (Kunen et al., 2005). Studies of diagnostic bias show, for example, that in the United States, Black patients are more likely than White patients to be diagnosed with schizophrenia instead of a mood disorder (Gara et al., 2012; Trierweiler et al., 2005). Black patients are also prescribed higher doses of medication than are White patients (Strakowski et al., 1993).

When a mental health clinician is not familiar with the social norms of the patient’s cultural background, the clinician may misinterpret certain behaviors as pathological and thus be more likely to diagnose a psychological disorder. So, for instance, the clinician might view a Caribbean immigrant family’s closeness as “overinvolvment” rather than as normal for that culture.

Other groups, such as low-income Mexican Americans, may have their mental illnesses underdiagnosed (Schmaling & Hernandez, 2005). Part of the explanation for the underdiagnosis may be that the constellation of symptoms experienced by some Mexican Americans does not fit within the classification system currently used in North America; another part of the explanation may be language differences between patient and clinician that make accurate assessment difficult (Kaplan, 2007b; Villaseñor & Waitzkin, 1999).

Bias is particularly important because when someone is said to have a psychological disorder, the diagnosis may be seen as a stigmatizing label that influences how other people—including the mental health clinician—view and treat the person. It may even change how a diagnosed person behaves and feels about himself or herself (Ben-Zeev et al., 2010; Eriksen & Kress, 2005). Such labels can lead some people with a psychological disorder to blame themselves and try to hide their problems (Corrigan & Watson, 2001; Reinberg, 2011). Feelings of shame may even lead them to refrain from obtaining treatment (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1999). Great strides have been made toward destigmatizing mental illness, although there is still a way to go. One organization devoted to confronting the stigma of mental illness is the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill (nami.org), which has a network of advocates—called Stigma-Busters—who combat incorrect and insensitive portrayals of mental illness in the media.

Reliability and Validity in Classification Systems

Reliable A property of classification systems (or measures) that consistently produce the same results.

Classification systems are most useful when they are reliable and valid. If a classification system yields consistent results over time, it is reliable. To understand what constitutes a reliable classification system, imagine the following scenario about Rose Mary Walls: Suppose she decided to see a mental health clinician because she was sleeping a lot, crying every day, and had no appetite. Further, she consented to have her interview with the clinician filmed for other clinicians to watch. Would every clinician who watched the video clip hear Rose Mary’s words and classify her behavior in the same way? Would every clinician diagnose her as having the same disorder? If so, then the classification system they used would be deemed reliable. But suppose that various clinicians came up with different diagnoses or were divided about whether Rose Mary even had a disorder. They might make different judgments about how her behaviors or symptoms fit into the classification system. If there were significant differences of opinion about her diagnosis among the clinicians, the classification system they used probably is not reliable.

Problems concerning reliability in diagnosis can occur when:

- the criteria for disorders are unclear and thus require the clinician to use considerable judgment about whether symptoms meet the criteria; or

- there is significant overlap among disorders, which can then make it difficult to distinguish among them.

Valid A property of classification systems (or measures) that actually characterize what they are supposed to characterize.

However, just because clinicians agree on a diagnosis doesn’t mean that the diagnosis is correct! For example, in the past, there was considerable agreement about the role of the devil in producing mental disorders, but we now know that this isn’t a correct explanation (Wakefield, 2010). Science is not a popularity contest; what the majority of observers believe at any particular point in time is not necessarily correct. Thus, another requirement for any classification system is that it needs to be valid. The categories must characterize what they are supposed to be classifying. Each disorder should have a unique set of criteria that correctly characterize the disorder.

Prognosis The likely course and outcome of a disorder.

The reliability and validity of classification systems are important in part because such systems are often used to study the etiology of a psychological disorder, its prognosis (the likely course and outcome of the disorder), and whether particular treatments will be effective. In order to use a classification system in this way, however, the prevalence of each disorder—the number of people who have the disorder in a given period of time—must be large enough that researchers are likely to encounter people with the disorder. (A related term is incidence, which refers to the total number of new cases of a disorder that are identified in a given time period.)

Prevalence The number of people who have a disorder in a given period of time.

In sum, a classification system should be reliable and valid in order to be as useful as possible for patients, clinicians, and researchers. Next, we’ll examine a commonly used classification system for psychological disorders—the system in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM).

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

Suppose that child welfare officials had spoken with Rex and Rose Mary Walls and required that the parents be evaluated by mental health professionals. How would a mental health clinician go about determining whether or not either of them had a disorder? What classification system would the clinician probably use? The classification system that most clinicians use in the United States is found in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, which is currently in its fifth edition. This guide, published by the American Psychiatric Association (2013), describes the characteristics of many psychological disorders and identifies criteria—the kinds, number, and duration of relevant symptoms—for diagnosing each disorder. This classification system is generally categorical, which means that someone either has a disorder or does not.

A different classification system, used in some parts of the world, is described in the International Classification of Diseases (ICD). The World Health Organization (WHO) develops the ICD, with its 11th edition released in 2017. The primary purpose of the ICD is to provide a framework for collecting health statistics worldwide. Unlike the DSM, however, the ICD includes many diseases and disorders, not just psychological disorders. In fact, until the sixth edition, the ICD only classified causes of death. With the sixth edition, the editors added diseases and mental disorders. Current versions of the mental disorders sections of the ICD and the DSM have been revised to overlap substantially. Research on prevalence that uses one classification system is now generally applicable to the other system.

The Evolution of DSM

When the original version of the DSM was published in 1952, it was the first manual to address the needs of clinicians rather than researchers (Beutler & Malik, 2002). At that time, Freud-inspired, psychodynamic theory was popular, and the DSM strongly favored the psychodynamic approach in its classifications. For example, it organized mental illness according to different types of conflicts among the id, ego, superego, and reality, as well as different patterns of defense mechanisms employed (American Psychiatric Association, 1952). The second edition of the DSM, published in 1968, had only minor modifications. The first two editions were criticized for problems with reliability and validity, which arose in part because their classifications relied on psychodynamic theory. Clinicians had to draw many inferences about the specific nature of patients’ problems, including the specific unconscious conflicts that motivated patients’ behavior.

The authors of the third edition (DSM-III), published in 1980, set out to create a classification system that had better reliability and validity. Unlike the previous editions, DSM-III:

- did not rest on the psychodynamic theory of psychopathology (or on any other theory);

- focused more on what can be observed than on what can be inferred;

- listed explicit criteria for each disorder and began to use available research results to develop those criteria; and

- included a system for clinicians and researchers to record diagnoses as well as additional information—such as related medical history—that may affect diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment.

Comorbidity The presence of more than one disorder at the same time in a given patient.

The weaknesses of DSM-III led to DSM-IV, published in 1994, which specified new disorders and revised the criteria for some of the disorders included in the previous edition. In 2000, the American Psychiatric Association published an expanded version of DSM-IV that included more current information about each disorder, such as new information about prevalence, course, issues related to gender and cultural factors, and comorbidity—the presence of more than one disorder at the same time in a given patient. This revised edition is called DSM-IV-TR, where TR stands for “Text Revision.” The list of disorders and almost all of the criteria in DSM-IV-TR were not changed, but the text discussion of the disorders was revised. DSM-IV and DSM-IV-TR defined 17 major categories of psychological problems, and nearly 300 specific mental disorders.

In 2013, the American Psychiatric Association published the fifth edition, DSM-5, which includes over 300 disorders (depending on how you count) across 22 categories, as shown in TABLE 3.1 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). The new edition was intended to address criticisms of DSM-IV and to incorporate more recent research findings about disorders that relate to the diagnostic criteria, and into what category they best fall. However, many have criticized DSM-5 as not addressing the flaws in DSM-IV and being less based on research than the previous edition (Frances, 2013; Greenberg, 2013). In fact, the National Institute of Mental Health, which funded research that used DSM-IV diagnoses to categorize patient’s symptoms, will not fund research using DSM-5 diagnoses (Insel, 2013).

| Neurodevelopmental Disorders Schizophrenia Spectrum and Other Psychotic Disorders Bipolar and Related Disorders Depressive Disorders Anxiety Disorders Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders Trauma- and Stressor-Related Disorders Dissociative Disorders Somatic Symptom and Related Disorders Feeding and Eating Disorders Elimination Disorders Sleep–Wake Disorders Sexual Dysfunctions Gender Dysphoria Disruptive, Impulse Control, and Conduct Disorders Substance-Related and Addictive Disorders Neurocognitive Disorders Personality Disordersw Paraphilic Disorders Other Mental Disorders Medication-Induced Movement Disorders and Other Adverse Effects of Medication Other Conditions That May Be a Focus of Clinical Attention |

| Source: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2013. |

The edition number went from Roman numbers (IV) to Arabic numbers (5) because the mental health professionals in charge of creating DSM-5 envisioned the fifth edition as “a living document,” with “Web-based releases” of refinements to the manual over time (5.1, 5.2, and so on; Kupfer, 2012). However, the idea of a living document with frequent updates has been criticized as creating confusion for clinicians and problems for researchers who need to compare results from studies across the updates (Rosenberg, 2013a).

The Evolution of DSM-5

The jury is still out on whether DSM-5 is an improvement over the previous edition, DSM-IV-TR. To understand some of the factors that led to the creation of DSM-5, we will use the example of the diagnosis of schizophrenia (see TABLE 3.2); this disorder is discussed in more detail in Chapter 12. The issues raised in the discussion that follows apply to most DSM-5 disorders.

|

|

|

| Source: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2013. |

Subjectivity in Determining Clinical Significance

Various editions of DSM have been criticized because their criteria require mental health professionals to draw subjective opinions. Consider the symptoms of schizophrenia in TABLE 3.2. DSM-5 instructs the clinician to determine whether, because of these symptoms, the individual’s functioning is “markedly below the level achieved prior to the onset.” (American Psychiatric Association, 2013, p. 99) Part of the problem is that this decision, to a certain extent, is subjective. DSM-5 does not specify what, exactly, markedly means. Not all professionals would consider the same patient’s dysfunction marked enough to qualify. These problems are complicated further if the clinician relies on the patient’s description of his or her previous level of functioning; the patient’s view of the past may be clouded by the present symptoms.

In a similar vein, consider the disorders known as adjustment disorders, which are characterized by a response, such as distress, that is “out of proportion to the severity or intensity of the stressor” (American Psychiatric Association, 2013. The clinician must determine whether an individual’s response is proportional. However, different people have different coping styles, and what seems to one clinician like an excessive response may be deemed normal by another clinician (Narrow & Kuhl, 2011).

Disorders as Categories, Not Continuous Dimensions

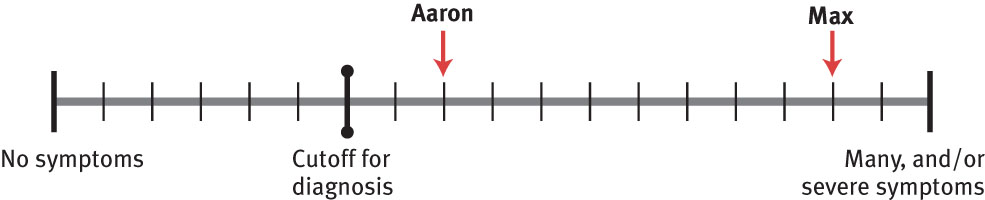

The criteria for disorders in DSM-5 are structured so that someone either has or does not have a given disorder. It’s analogous to the old adage about pregnancy: A woman can’t be a little bit pregnant—she either is or isn’t pregnant. But critics argue that many disorders may exist along continua (continuous gradations), meaning that patients can have different degrees of a disorder (Kendell & Jablensky, 2003).

Consider, for example, two young men who have had the diagnosis of schizophrenia for 5 years. Aaron has been living with roommates and attending college part time; Max is living at home, continues to hallucinate and have delusions, and cannot hold down a volunteer job. (Hallucinations are sensations that are so vivid that the perceived objects or events seem real, although they are not, and delusions are persistent false beliefs that are held despite evidence that the beliefs are incorrect or exaggerate reality.) Over the holidays, both men’s symptoms got worse, and both were hospitalized briefly. Since being discharged from the hospital, Aaron has had only mild symptoms, but Max still can’t function independently, even though he no longer needs to be in the hospital. The categorical diagnosis of schizophrenia lumps both of these patients together, but the intensity of their symptoms suggests that clinicians should have different expectations, goals, treatments, and prognoses for them. As shown in Figure 3.1, on a dimensional scale, one of them is likely to be diagnosed with mild schizophrenia, whereas the other is likely to be diagnosed with severe schizophrenia.

To address this general criticism, DSM-5 includes optional dimensional scales for some disorders; clinicians can rate the severity of symptoms (from mild to severe). For instance, DSM-5 includes a set of scales to rate each of eight symptoms related to schizophrenia. However, such ratings are optional and the decision to diagnose a patient is still categorical (McHugh & Slavney, 2012).

People with Different Symptoms Can Be Diagnosed With the Same Disorder

For many DSM-5 disorders, including schizophrenia, a person needs to have only some of the symptoms in order to be diagnosed with the disorder. For example, in TABLE 3.2, a person needs to have only two out of the five symptoms. Consider three people who have been diagnosed with schizophrenia: One has delusions and hallucinations. Another has disorganized speech and disorganized behavior but no delusions or hallucinations. And a third person classified as having schizophrenia has negative symptoms and delusions, but not disorganized behavior or hallucinations. Taken together, these three people with schizophrenia display heterogeneous symptoms: The sets of symptoms are different from each other. Nevertheless, the three people are classified with the same disorder according to DSM-5. People with different combinations of symptoms may have developed the disorder in different ways, and different treatments might be effective. Thus, the DSM-5 diagnostic system may obscure important differences among types of a given mental disorder (Malik & Beutler, 2002).

Duration Criteria Are Arbitrary

Each set of criteria for a disorder specifies a minimum amount of time that symptoms must be present for a patient to qualify for that diagnosis (see the last bullet point in TABLE 3.2). However, the particular duration, such as that noted for bipolar disorder (which requires that the symptoms be present for at least 1 week), is often arbitrary and not supported by research (Brauser, 2012; Greenberg, 2013).

Some Sets of Criteria Are too Restrictive

Some categories of disorders in DSM-5 include two types of diagnoses that can be used when a person’s symptoms do not meet the necessary minimum criteria for the disorder that is the best fit, but the person is nonetheless significantly distressed or impaired. At least for some categories of disorders in DSM-IV, this type of diagnosis (called not otherwise specified in DSM-IV) was the most frequent diagnosis in the category (Keel et al., 2011). The two types in DSM-5 are Other Specified _______ (fill in the blank with the category of disorder) and Unspecified ____________. With the former, the clinician notes why—in what ways—the criteria are not met (e.g., the symptoms have not yet been present long enough); with the latter, the clinician chooses not to specify why the criteria are not met. Thus, people might be diagnosed with either of these “other” type disorders because their symptoms do not meet the minimum duration necessary for a diagnosis of a specific disorder; alternatively, they might be diagnosed with one of these “other” disorders because they don’t have enough symptoms to meet the criteria for that specific disorder.

Psychological Disorders Are Created to Ensure Payment

With each edition of DSM, the number of disorders increased, reaching over 300 with DSM-5. Does this mean that more types of mental disorders have been discovered and classified? Not necessarily. This increase may, in part, reflect economic pressures in the mental health care industry (Eriksen & Kress, 2005). Today, in order for a mental health facility or provider to be paid or a patient to be reimbursed by health insurance companies, the patient must have symptoms that meet a DSM-5 diagnosis. The more disorders that are included in a new edition of DSM, then, the more likely it is that a patient’s treatment will be paid for or reimbursed by health insurance companies. But this does not imply that all of the disorders are valid from a scientific perspective.

To address the criticism about the growing number of disorders, the authors of DSM-5 set out to maintain or reduce the total number of disorders. To achieve this goal, and still add new disorders, in some cases disorders have been consolidated: for instance, what was a disorder in DSM-IV may now be a subtype of another disorder in DSM-5. Using such “accounting” methods, the authors of DSM-5 claim to have achieved their goal while at the same time potentially increased the types of symptoms for which health insurance payment may be possible.

Social Factors Are Deemphasized

Perhaps because DSM-5 does not generally address etiological factors (the causes of a disorder), it does not explicitly recognize social factors that contribute to disorders. DSM-5 states that its diagnoses are not supposed to apply to conflicts that are mainly between an individual and society but rather to conflicts within an individual (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). However, this distinction is often difficult to make (Caplan, 1995). For instance, people can become depressed in response to a variety of social stressors: after losing their jobs, after they are exposed to systematic discrimination, after emigrating from their native country, or after experiencing other social and societal conflicts.

Social factors are further deemphasized in DSM-5 with the presumption of neurobiological causes of mental illness, at least with some categories of disorders, such as neurodevelopmental disorders and neurocognitive disorders.

Comorbidity Is Common

About half of the people who have been diagnosed with a DSM-IV disorder have at least one additional disorder; that is, they exhibit comorbidity (Kessler et al., 2005). This will probably be true with DSM-5 because the criteria for many disorders have not become more stringent (which would reduce the number of people diagnosed with the disorders); in fact, in some cases, the criteria in DSM-5 have actually become less stringent, so that they apply to more people. This high comorbidity raises the question of whether some disorders in DSM-5 are actually distinct. For instance, half of the people who meet the criteria for major depressive disorder also have an anxiety disorder (Kessler et al., 2003). Such a high rate of comorbidity suggests that these two types of DSM-5 disorders often represent different facets of the same underlying problem (Hyman, 2011; Kendler et al., 2011). This possibility raises questions about validity and makes DSM-5 diagnoses less useful to clinicians and researchers.

DSM-5 Is Unscientific and Lacks Rigor

The process leading up to the publication of DSM-5 has been criticized on a number of grounds, some of which stem from a rush to meet a publication deadline that some argued was set arbitrarily. Criticisms include (Strakowski & Frances, 2012):

- Proposed diagnoses and criteria were not adequately field-tested: Mental health professionals in various types of settings (e.g., hospitals, clinics) tried using the new manual to diagnose patients. Unfortunately, these field tests showed disappointingly low reliability for some disorders (Ghaemi, 2012; Greenberg, 2013). That is, using the new criteria, mental health clinicians didn’t agree on what diagnosis was most appropriate for a given patient. After field testing, some of the criteria were revised, in the hope of increasing reliability, and these new criteria (and wording) were supposed to have another round of field testing.

- However, the planned final stage of research on the new criteria was cancelled because of pressure to meet the planned publication deadline. One consequence is that the wording of the criteria that were tested in earlier phases isn’t the wording in the final version of DSM-5; problems with reliability and validity of the diagnoses are thus more likely (Greenberg, 2013).

- Many disorders were proposed as additions to DSM-5, some of which were very controversial, and others were placed in a section of the manual (equivalent to an appendix) for disorders that need further study before being accepted into the regular part of the manual. An example is attenuated psychosis syndrome, which was originally named psychosis risk syndrome because the diagnosis is for people thought to be at risk to develop a psychotic disorder. Given the controversial nature of such disorders, some researchers argued that they should not have been included even in an appendix because the implications of adding the new disorder, and of deciding its criteria for further study, were not thought through well enough (Cornblatt & Correll, 2010).

As Allen Frances, organizer of and contributor to several previous DSM editions (DSM-III, DSM-IV, DSM-IV-TR) noted about DSM-5:

Each change in a DSM is an opportunity for clinical and forensic misuse, with unpredictable and harmful unintended consequences. Changes are also costly to psychiatric research in direct ways, such as the cost of changing instruments midstream, and even more importantly in indirect ways, such as the [difficulty comparing research results for a given disorder using diagnostic criteria that differ across editions]…It might be worth the risks and costs of DSM-5 changes if there were compelling science supporting them, but there isn’t.

(Strakowski & Frances, 2012).

Although the criticisms of DSM-5 must be taken seriously, the clinical chapters of this book (Chapters 5–15) are generally organized according to DSM-5 categories and criteria. The DSM has been, to date, by far the most widely used classification system for diagnosing psychological disorders.

The People Who Diagnose Psychological Disorders

Who, exactly, are the mental health professionals who might diagnose Rex or Rose Mary Walls, or anyone else who might be suffering from a psychological disorder? As you will see, there are different types of mental health professionals, each with a different type of training. The type of training can influence the kinds of information that clinicians pay particular attention to, what they perceive, and how they interpret the information. However, regardless of the type of training they receive, all mental health professionals must be licensed in the state in which they practice (or board certified, in the case of psychiatrists); licensure indicates that they have been appropriately trained to diagnose and treat mental disorders.

Clinical Psychologists and Counseling Psychologists

Clinical psychologist A mental health professional who has a doctoral degree that requires several years of related coursework and several years of treating patients while receiving supervision from experienced clinicians.

A clinical psychologist generally has a doctoral degree, either a Ph.D. (doctor of philosophy) or a Psy.D. (doctor of psychology), that is awarded only after several years of coursework and several years of treating patients while receiving supervision from experienced clinicians. People training to be clinical psychologists also take other courses that may include neuropsychology and psychopharmacology. In addition, clinical psychologists with a Ph.D. will have completed a dissertation—a major, independent research project. Programs that award a Psy.D. in clinical psychology place less emphasis on research.

Clinical neuropsychologists are a particular type of clinical psychologist. Clinical neuropsychologists concentrate on characterizing the effects of brain damage and neurological diseases (such as Alzheimer’s disease) on thoughts (that is, mental processes and mental contents), feelings (affect), and behavior. Sometimes, they help design and conduct rehabilitation programs for patients with brain damage or neurological disease.

Counseling psychologist A mental health professional who has either a Ph.D. degree from a psychology program that focuses on counseling or an Ed.D. degree from a school of education.

A counseling psychologist might have a Ph.D. from a psychology program that focuses on counseling or might have an Ed.D. (doctor of education) degree from a school of education. Training for counseling psychologists is similar to that of clinical psychologists except that counseling psychologists tend to have more training in vocational testing, career guidance, and multicultural issues, and they generally don’t receive training in neuropsychology. Counseling psychologists also tend to work with healthier people, whereas clinical psychologists tend to have more training in psychopathology and often work with people who have more severe problems (Cobb et al., 2004; Norcross et al., 1998). The distinction between the two types of psychologists, however, is less clear-cut than in the past, and both types may perform similar work in similar settings.

Clinical psychologists and counseling psychologists are trained to perform research on the nature, diagnosis, and treatment of mental illness. They also both provide psychotherapy, which involves helping patients better cope with difficult experiences, thoughts, feelings, and behavior. Both types of psychologists also learn how to administer and interpret psychological tests in order to diagnose and treat psychological problems and disorders more effectively.

Psychiatrists, Psychiatric Nurses, and General Practitioners

Psychiatrist A mental health professional who has an M.D. degree and has completed a residency that focuses on mental disorders.

Someone with an M.D. (doctor of medicine) degree can choose to receive further training in a residency that focuses on mental disorders, becoming a psychiatrist. A psychiatrist is qualified to prescribe medications; psychologists in the United States, except for appropriately trained psychologists in New Mexico and Louisiana, currently may not prescribe medications. (Other states are considering allowing appropriately trained psychologists to prescribe.) But psychiatrists usually have not been taught how to interpret and understand psychological tests and have not been required to acquire detailed knowledge of research methods used in the field of psychopathology.

Psychiatric nurse A mental health professional who has an M.S.N. degree, plus a C.S. certificate in psychiatric nursing.

A psychiatric nurse has an M.S.N. (master of science in nursing) degree, plus a C.S. (clinical specialization) certificate in psychiatric nursing; a psychiatric nurse may also be certified as a psychiatric nurse practitioner (N.P.). Psychiatric nurses normally work in a hospital or clinic to provide psychotherapy; in these settings, they work closely with physicians to administer and monitor patient medications. Psychiatric nurses are also qualified to provide psychotherapy in private practice and are permitted in some states to monitor and prescribe medications independently (Haber et al., 2003).

Although not considered a mental health professional, a general practitioner (GP), or family doctor (the doctor you may see once a year for a checkup), may inquire about psychological symptoms, may diagnose a psychological disorder, and may recommend to patients that they see a mental health professional. Responding to pressure to reduce insurance companies’ medical costs, general practitioners frequently prescribe medication for some psychological disorders. However, studies have found that treatment with medication is less effective when prescribed by a family doctor than when prescribed by psychiatrists, who are specialists in mental disorders and more familiar with the nuances of such treatment (Lin et al., 2000; Wang et al., 2005; Wilson et al., 2003).

Mental Health Professionals with Master’s Degrees

Social worker A mental health professional who has an M.S.W. degree and may have had training to provide psychotherapy to help individuals and families.

In addition to psychiatric nurses, some other mental health professionals have master’s degrees. Most social workers have an M.S.W. (master of social work) degree and may have had training to provide psychotherapy to help individuals and families. Social workers also teach clients how to find and benefit from the appropriate social services offered in their community. For example, they may help clients to apply for Medicare or may facilitate home visits from health care professionals. Most states also license marriage and family therapists (M.F.T.s), who have at least a master’s degree and are trained to provide psychotherapy to couples and families. Other therapists may have a master’s degree (M.A.) in some area of counseling or clinical psychology, which indicates that their training consisted of fewer courses and research experience, and less supervised clinical training than that of their doctoral-level counterparts. Some counselors may have had particular training in pastoral counseling, which provides counseling from a spiritual or faith-based perspective.

TABLE 3.3 reviews the different types of mental health clinicians.

| Type of clinician | Specific title and credentials |

|---|---|

| Doctoral-level psychologists | Clinical psychologists (including clinical neuropsychologists) and counseling psychologists have a Ph.D., Psy.D., or Ed.D. degree and have advanced training in the treatment of mental illness. |

| Medical personnel | Psychiatrists and general practitioners have a M.D. degree; psychiatrists have had advanced training in the treatment of mental illness. Psychiatric nurses have a M.S.N. degree and have advanced training in the treatment of mental illness. |

| Master’s-level mental health professionals | Social workers with a master’s degree (M.S.W.), marriage and family therapists (M.F.T.), and master’s level counselors (M.A.) are mental health clinicians who have received specific training in helping people with problems in daily living or with mental illness. Psychiatric nurses have master’s level training. |

Thinking Like A Clinician

Your abnormal psychology class watches a videotape of a clinical interview with Peter, a man who has been diagnosed with schizophrenia. Your professor has been researching new criteria for diagnosing schizophrenia and has asked you and your classmates to determine whether Peter does, in fact, have schizophrenia according to the new criteria. If you and your classmates disagree with each other about his diagnosis, what might that indicate about the criteria’s reliability and validity, and what might it indicate about the interview itself?

The professor then asks you to decide whether Peter has schizophrenia as defined by the DSM-5 criteria. What are some of the advantages and disadvantages of using DSM-5? Based on what you have read, what factors, other than the specifics of Peter’s symptoms, might influence your assessment? (Hint: Think of biases.) Should Peter be diagnosed with schizophrenia, might there be any benefits to him that come with the diagnosis, based on what you have read? What might be the possible disadvantages for Peter of being diagnosed with schizophrenia? Be specific in your answers.