3.2 Assessing Psychological Disorders

People came to know about Rose Mary and Rex Walls through the eyes of their daughter, Jeannette. In her memoir, Jeannette reports incidents that seem to be clear cases of neglect and irresponsible behavior. How might a mental health clinician or researcher have gone about assessing Rose Mary’s or Rex’s mental health? Although mental health clinicians might read Jeannette Walls’s memoir, hear her speak about her parents, or even see brief video clips of Rose Mary Walls, the information conveyed by those accounts isn’t adequate to make a clinical assessment: Jeannette’s memoir—and Rose Mary’s brief statements on videotape—portray what Jeannette and the video directors chose to include; we don’t know about events that were not discussed or portrayed, and we don’t know how accurate Jeannette’s childhood memories are. Other people’s accounts of an individual’s mental health generally provide only narrow slices of information—brief glimpses as seen from their own points of view, none of which is that of a mental health clinician in this case. Without use of the formal tools and techniques of clinical assessment, any conclusions are likely to be speculative.

Were it possible to obtain information about Rose Mary and Rex Walls directly, what specific information would a clinician want to know in order to make a diagnosis and recommendations for treatment? More generally, what types of information are included in a clinical assessment?

A complete clinical assessment can include various types of information regarding the three main categories that underlie the neuropsychosocial model:

- neurological and other biological factors (i.e., the structure and functioning of brain and body),

- psychological factors (i.e., behavior, emotion and mood, mental processes and contents, past and current ability to function), and

- social factors (i.e., the social context of the patient’s problems, the living environment and community, family history and family functioning, history of the person’s relationships, and level of financial resources and social support available).

Most types of assessment focus primarily on one type of factor. We’ll consider assessments of each of these main types of factors in the following sections.

Assessing Neurological and Other Biological Factors

In some cases, clinicians assess neurological (and other biological) functioning in order to determine whether abnormal mental processes and mental contents, affect, or behaviors arise from a medical problem, such as a brain tumor or abnormal hormone levels. In other cases, researchers seek to understand neurological and other biological factors that may be related to a particular disorder because this information might provide clues for possible treatments. Although neurological and other biological factors are not generally part of the DSM criteria for diagnosing mental disorders, the search for neurological and other biological markers or indicators of various psychological disorders has proceeded at a rapid pace over the past decade. It is clearly only a matter of time before these sorts of factors will be part of the standard diagnostic criteria for many psychological disorders (Lieberman, 2011).

Assessing Abnormal Brain Structures with X-Rays, CT Scans, and MRIs

Computerized axial tomography (CT) A neuroimaging technique that uses X-rays to build a three-dimensional image (CT or CAT scan) of the brain.

Some psychological disorders, such as schizophrenia, appear to involve abnormalities of the structure of the brain. This is why clinical assessments sometimes make use of scans of a patient’s brain. Neuroimaging techniques provide images of the brain. The oldest neuroimaging technique involves taking pictures of a person’s brain using X-rays. A computer can then analyze these X-ray images and reconstruct a three-dimensional image of the brain. Computerized axial tomography (CT) (tomography is from a Greek word for “section”) builds an image of a person’s brain, slice by slice, creating a CT scan (sometimes called a CAT scan).

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) A neuroimaging technique that creates especially sharp images of the brain by measuring the magnetic properties of atoms in the brain.

A more recent technology, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), makes especially sharp images of the brain, which allows more precise diagnoses when brain abnormalities are subtle. MRI makes use of the magnetic properties of different atoms. By detecting different atoms and combining the signals into images, MRI can indicate the location of damaged tissue and can reveal particular parts of the brain that are larger or smaller than normal. For instance, an MRI can reveal the shrinkage of brain tissue that typically arises with chronic alcoholism (Rosenbloom et al., 2003); had Rex Walls had an MRI, it might well have shown that his brain had such shrinkage.

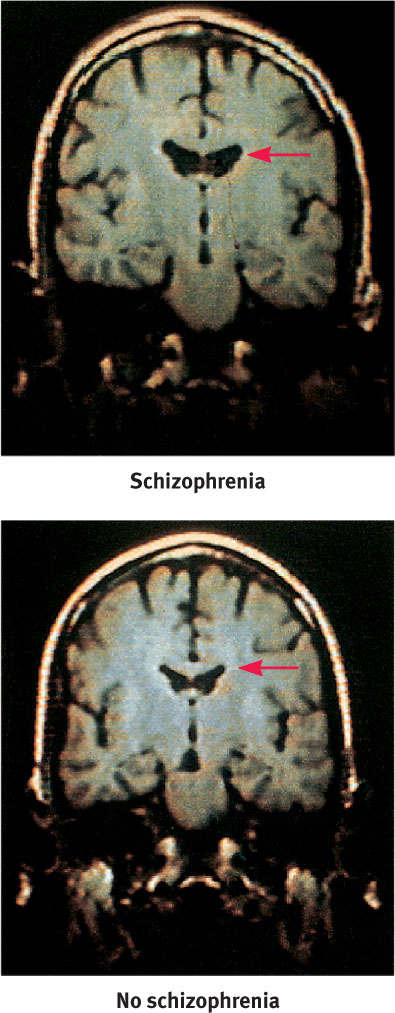

CT scans and MRIs can provide amazing images of the structure of the living brain, which may provide information that can help to diagnose psychological conditions. For example, some people with schizophrenia have larger ventricles (interior, fluid-filled spaces in the brain) than do people who do not have the disorder (Schneider-Axmann et al., 2006). These larger ventricles may occur, at least in part, because some of the surrounding brain tissue is smaller than normal (Gaser et al., 2004).

Assessing Brain Function with PET Scans and fMRI

Some mental disorders are associated not with abnormal brain structures (physical makeup) but rather with abnormal brain functioning (how the brain operates). The brain can also produce abnormal thoughts, feelings, and behaviors because it functions inappropriately. Researchers use different types of brain scans to assess brain functioning.

We’ve just talked about how certain neuroimaging techniques can reveal brain structure, but how can researchers observe brain functioning? A key fact is that when a part of the brain is active, more blood (which transports oxygen and nutrients) flows to it, a little like the way that more electricity flows into a house when more appliances are turned on.

The neurons draw more blood while they are sending and receiving signals than they do when they are not activated, because the activity increases their need for oxygen and nutrients. Because neurons in the same area of the brain tend to work together, specific areas of the brain will have greater blood flow while a person performs particular tasks.

In the field of psychopathology, researchers use functional neuroimaging to identify brain areas related to specific aspects of a disorder. For example, in one study, researchers asked participants with social phobia, who were afraid of speaking in public, to speak to a group and also to speak in private while their brains were scanned. Speaking in public activated key parts of the limbic system, particularly the amygdala, more than did speaking in private (Tillfors et al., 2001). As noted in Chapter 2, the amygdala is involved in strong emotion, particularly fear. This part of the brain was not activated when people without a social phobia were tested. Other researchers have reported similar results for other sorts of phobias (Pissiota et al., 2003).

Positron emission tomography (PET) A neuroimaging technique that measures blood flow (or energy consumption) in the brain and requires introducing a very small amount of a radioactive substance into the bloodstream.

The functional neuroimaging technique used in the study of social phobia just described was positron emission tomography (PET), one of the most important methods for measuring blood flow (or energy consumption) in the brain. PET requires introducing a very small amount of a radioactive substance into the bloodstream. While a person performs a task, as active regions of the brain take up more blood they take up more of the radioactive substance than do less active regions. The relative amounts of radiation from different areas of the brain are measured and sent to a computer, which constructs a three-dimensional image of the brain that shows the levels of activity in the different areas. In PET images, higher radiation (greater activity) typically is illustrated with brighter colors.

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) A neuroimaging technique that uses MRI to obtain images of brain functioning, which reveal the extent to which different brain areas are activated during particular tasks.

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) is currently the most widely used method for measuring human brain function. When a region of the brain is activated, it draws blood more quickly than the oxygen carried by the hemoglobin in the blood can be used. This means that red blood cells with oxygenated hemoglobin accumulate in the activated region—and this increase is what is measured in an fMRI scan. Brain regions that are not activated (or are activated less strongly) when a person is performing a particular task (such as speaking in public or looking at pictures) draw less blood, and the oxygen carried by the blood gets used up. The difference in oxygen levels due to brain activity is reflected in the fMRI images.

The advantages of fMRI over PET include the absence of radiation and the ability to construct brain images showing activation that occurs in just a few seconds. Disadvantages include the requirement that a participant must lie very still in the narrow tube of a noisy machine (which some people find uncomfortable).

Neuropsychological Assessment

Neuropsychological testing The employment of assessment techniques that use behavioral responses to test items in order to draw inferences about brain functioning.

An assessment of neurological factors may include neuropsychological testing, which uses behavioral responses to test items in order to draw inferences about brain functioning. Assessing neuropsychological functioning allows clinicians and researchers to distinguish the effects of brain damage from the effects of psychological problems (for example, disrupted speech can be caused by either of these). Neuropsychological assessment is also used to determine whether brain damage is contributing to psychological problems (for example, frontal lobe damage can disrupt the ability to inhibit aggressive behavior).

Neuropsychological tests range from those that assess complex abilities (such as judgment or planning) to those that assess a relatively specific ability (such as the ability to recognize faces). Other neuropsychological tests, such as the Bender Visual-Motor Gestalt Test-II (2nd edition) (Bender, 1963; Brannigan & Decker, 2003), assess more complex functions. Patients are shown a series of drawings that range from simple to complex and are asked to reproduce them. This test assesses the integration of visual and motor functioning, which involves many distinct parts of the brain. The test may be used to help diagnose various problems, including learning disorders and memory problems (Brannigan & Decker, 2006).

Assessing Psychological Factors

During an assessment, clinicians and researchers often seek to identify the ways in which psychological functioning is disordered and the ways in which it is not. For instance, a clinical assessment would shed light on the extent to which Rex Walls’s problems were primarily a result of his drinking or arose from underlying distress or impairments that may have been masked by his pronounced drinking.

Certain areas of psychological functioning—mental processes and mental contents, affect, and behavior—are often directly related to DSM-5 criteria for specific disorders. Further, these areas are frequently the most relevant for determining a person’s current and future ability to function in daily activities.

Mental health researchers and clinicians employ a variety of assessment techniques and tools to evaluate psychological functioning, including interviews and tests of cognitive and personality functioning. Which tools and techniques are used depends on the purpose of the assessment.

Clinical Interview

Clinical interview A meeting between clinician and patient during which the clinician asks questions related to the patient’s symptoms and functioning.

An important tool used to assess psychological functioning is the clinical interview, a meeting between clinician and patient during which the clinician asks questions related to the patient’s symptoms and functioning. A clinical interview provides two types of information: the content of the answers to the interview questions, and the manner in which the person answered them (Westen & Weinberger, 2004). Questions may focus on symptoms, general functioning, degree and type of impairment, and the patient’s relevant history. Clinicians generally use three types of interviews: unstructured, structured, or semistructured.

In an unstructured interview, the clinician asks whatever questions he or she deems appropriate, depending on the patient’s responses. The advantage of an unstructured interview is that it allows the clinician to pursue topics and issues specific to the patient. However, different clinicians who use this approach to interview the same patient may arrive at different diagnoses, because each clinician’s interview may cover different topics and therefore gather different information. Another problem with unstructured interviews is that the interviewer may neglect to gather important information about the context of the problem and the individual’s cultural background.

In a structured interview, conversely, the clinician uses a fixed set of questions to guide the interview. A structured interview is likely to yield a more reliable diagnosis because each clinician asks the same set of questions. However, such a diagnosis may be less valid, because the questions asked may not be relevant to the patient’s particular symptoms, issues, or concerns (Meyer, 2002b). That is, different clinicians using a structured interview may agree on the diagnosis, but all of them may be missing the boat about the nature of the problem and may diagnose the wrong disorder.

A semistructured interview, discussed in more detail later, combines elements of both of the other types: Specific questions guide the interview, but the clinician also has the freedom to pose additional questions that may be relevant, depending on the patient’s answers to the standard questions.

Observation

All types of interviews provide an opportunity for the clinician or researcher to observe and make inferences about different aspects of a patient:

- Appearance. In addition to obvious aspects of appearance (whether the person has bathed recently and is dressed appropriately), signs of disorders can sometimes be noted by carefully observing subtle aspects of a person’s appearance. For example, patients with the eating disorder bulimia nervosa (to be discussed in Chapter 10) may regularly induce vomiting; as a result of repeated vomiting, their parotid glands, located in the cheeks, may swell and create a somewhat puffy look to the cheeks (similar to a chipmunk’s cheeks).

- Behavior. The patient’s body language, facial expression, movements, and speech can provide insights into different aspects of psychological functioning:

- Emotions. What emotions does the patient convey? The clinician can observe the patient’s expression of distress (or lack thereof) and emotional state (upbeat, “low,” intense, uncontrollable, inappropriate to the situation, or at odds with the content of what the patient says).

- Movement. The patient’s general level of movement—physical restlessness or a complete lack of movement—may indicate abnormal functioning.

- Speech. Clinicians observe the rate and contents of the patient’s speech: Speaking very quickly may suggest anxiety, mania, or certain kinds of substance abuse; speaking very slowly may suggest depression or other kinds of substance abuse.

- Mental processes. Some behaviors reveal characteristics of mental processes. Do the patient’s mental processes appear to be unusual or abnormal? Does the patient appear to be talking to someone who is not in the room, which would suggest that he or she is having hallucinations? Can the patient remember what the clinician just asked? Does the patient flit from topic to topic, unable to stay focused on answering a single question?

Behaviors observed during a clinical interview can, in some cases, provide more information than the patient’s report about the nature of the problem. In other cases, such observations round out an assessment; it is the patient’s own report of the problem—its history and related matters—that provides the foundation of the interview. In any case, the clinician must keep in mind that “unusual” behavior should perhaps be interpreted differently for patients from different cultural backgrounds.

Patient’s Self-Report

Some symptoms cannot be observed directly, such as the hallucinations that characterize schizophrenia, or the worries and fears that characterize some anxiety disorders. Thus, the patient’s own report of his or her experiences is a crucial part of the clinical assessment.

GETTING THE PICTURE

age footstock/SuperStock

At some point in the interview process, the clinician will ask about the patient’s history—past factors or events that may illuminate the current difficulties—and the patient will report such information about himself or herself. For example, the clinician will ask about current and past psychological or medical problems and about how the patient understands these problems and possible solutions to them. The clinician will inquire about substance use, sexual or physical abuse or other traumatic experiences, economic hardships, relationships with family members and others, and thoughts about suicide. The patient’s answers help the clinician put the patient’s current difficulties in context and determine whether his or her psychological functioning is maladaptive or adaptive, given the environmental circumstances (Kirk & Hsieh, 2004).

Malingering Intentional false reporting of symptoms or exaggeration of existing symptoms, either for material gain or to avoid unwanted events.

Some patients, however, intentionally report having symptoms that they don’t actually have or exaggerate symptoms that they do have, either for material gain or to avoid unwanted events (such as criminal prosecution); such behavior is the hallmark of malingering. For instance, a malingering soldier may exaggerate his or her anxiety symptoms and claim to have posttraumatic stress disorder in order to avoid further combat. Malingering contrasts with factitious disorder, which occurs when someone intentionally falsely reports or induces medical or psychological symptoms in order to receive attention. Whereas both malingering and factitious disorder involve deception—inventing or exaggerating symptoms—the motivations are different. Unlike those with malingering, people with factitious disorder do not deceive others about the symptoms for material gain or to avoid negative events.

Factitious disorder A psychological disorder marked by the false reporting or inducing of medical or psychological symptoms in order to receive attention.

Most patients intend to report their current problems and history as accurately as possible. Nevertheless, even honest self-reports are subject to various biases. Most fundamentally, patients may accurately report what they remember, but their memory of the frequency, intensity, or duration of their symptoms may not be entirely accurate. As we noted in Chapter 2, emotion can bias what we notice, perceive, and remember.

Another bias that can affect what patients say about their symptoms is reporting bias—inaccuracies or distortions in a patient’s report because of a desire to appear in a particular way (Meyer, 2002b). In some cases, patients may not really know the answer to a question asked in a clinical interview. For instance, when asked, “Why did you do that?” they may not have thought about their motivation before and may not really be aware of what it was but instead create an answer on the spot (Westen & Weinberger, 2004). In other cases, people’s psychological functioning is sufficiently impaired that they confuse their internal world—their memories, fears, beliefs, fantasies, or dreams—with reality, which leads to inaccuracies in self-reports.

Thus, although a patient’s self-report is important, it has limitations. Similarly, when interviewing children, the clinician must be sensitive to the fact that they may lack adequate insight and/or the verbal ability to reliably report their mental health status.

Semistructured Interviews

Because clinicians sometimes want to be sure to cover specific ground with their questions, they may use a semistructured interview format, asking a list of standard questions but formulating their own follow-up questions. The follow-up questions are based on patients’ responses to the standard questions. One set of questions that assesses a patient’s mental state at the time of the interview is the mental status exam. In a mental status exam, the clinician asks the patient to describe the problem, its history, and the patient’s functioning in different areas of life. Other standard questions in the mental status exam probe the patient’s ability to reason, to perform simple mathematical computations, and to assess possible problems in memory and judgment. The clinician uses the patient’s answers to the standard questions to develop hypotheses about possible diagnoses and difficulties with functioning, and then asks other questions to obtain additional information. For instance, as part of the mental status exam, patients are routinely asked whether they remember their own name, the date and year, and who is president. If the patient doesn’t remember correctly who the current president is, the clinician might ask other, more detailed questions involving different aspects of memory—such as memories of other languages spoken, of more distant events or important personal events in the recent past—which may reflect an underlying neurological problem. People from other cultures may answer some of the questions in a mental status exam in unconventional ways, and clinicians must take care not to infer that “different” is “abnormal.”

A mental status exam assesses cognitive, emotional, and behavioral functioning broadly, and the standard questions are not designed to obtain specific information that corresponds to the categories in DSM-5. The interviewer can arrive at a diagnosis based on answers to both standard and follow-up questions, but the goal of the mental status exam is more than diagnosis: It creates a portrait of the individual’s general psychological functioning. The mental status exam contrasts with another semistructured interview format, the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM (SCID; First et al., 1997, 2002). The SCID is generally used when the interview is part of a research project and is designed to assist the researcher in diagnosing patients according to DSM criteria.

Clinical interviews provide a wealth of information about the patient’s symptoms and general functioning, as well as about the context in which the symptoms arose and continue. However, a thorough clinical interview can be time-consuming and may not be as reliable and valid as assessment techniques that utilize tests.

Tests of Psychological Functioning

Many different tests are available to assess various areas of psychological functioning. Some tests assess a relatively wide range of abilities and areas of functioning (such as intelligence or general personality characteristics). Other tests assess a narrow range of abilities, particular areas of functioning, or specific symptoms (such as the ability to remember new information or the tendency to avoid social gatherings).

Cognitive Assessment

One tool to assess cognitive functioning is an intelligence test. Clinicians typically use the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, 4th edition (WAIS-IV, revised in 2008), or the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, 4th edition (WISC-IV, revised in 2003), depending on the age of the patient. Numerical results of these tests yield an intelligence quotient (IQ); the average intelligence in a population is set at a score of 100, with normal intelligence ranging from 85 to 115. IQ scores of 70 to 85 are considered to be in the borderline range, and scores of 70 and below signify mental impairment. However, the single intelligence score is not the only important information that the WAIS-IV and WISC-IV provide. Both of these tests include subtests that assess four types of abilities:

- verbal comprehension (i.e., the ability to understand verbal information);

- perceptual reasoning (i.e., the ability to reason with nonverbal information);

- working memory (i.e., the ability to maintain awareness and mentally manipulate new information); and

- processing speed (i.e., the ability to focus attention and quickly utilize information).

In addition, the WAIS-IV and WISC-IV are devised so that the examiner can compare an individual’s responses on each of the subtests to the responses of other people of the same age and sex. Information about specific subtests helps the examiner determine the individual’s pattern of relative strengths and weaknesses in intellectual functioning.

Current versions of intelligence tests have been designed to minimize the influence of cultural factors, in part by excluding test items that might require cultural knowledge that is unique to one group (and would thus put members of other groups at a disadvantage) (Kaufman et al., 1995; Poortinga, 1995).

Personality Assessment

Various psychological tests assess different aspects of personality functioning.

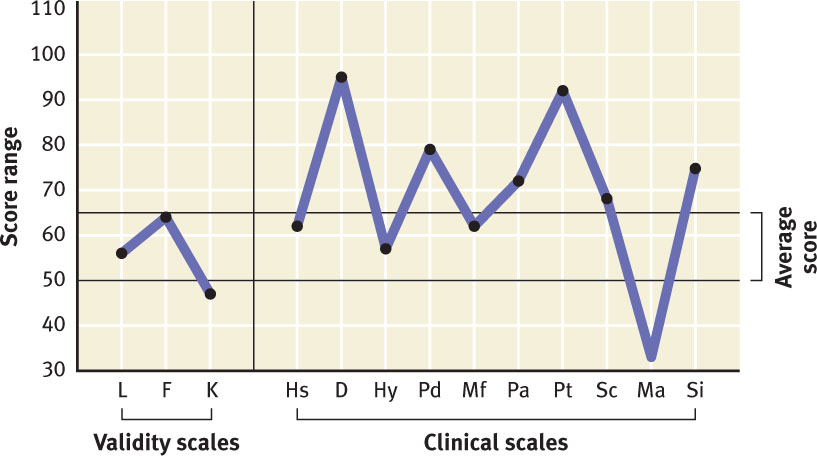

Inventories In order to assess general personality functioning, a clinician may use an -inventory—a questionnaire with items pertaining to many different problems and aspects of personality. An inventory can indicate to a clinician what problems and disorders might be most likely for a given person. Inventories usually contain test questions that are sorted into different scales, with each scale assessing a different facet of personality. The most commonly used inventory is the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory, 2nd edition (MMPI-2; Butcher et al., 1989); see TABLE 3.4 for the scales, and Figure 3.2 for the sample profile. Originally developed in the 1930s to identify people with mental illness, it was revised in 1989 to include norms of people from a wider range of racial, ethnic, and other groups and to update specific items; the scores were recalibrated in 2003, in a form referred to as the MMPI-2-RF, where the new suffix stands for “Restructured Form.” The MMPI-2 consists of 567 questions about the respondent’s behavior, emotions, mental processes, mental contents, and other characteristics. The respondent rates each question as being true or false about himself or herself. Test-takers generally require about 60 to 90 minutes to complete the inventory. (There is also a short form, with 370 items.) The MMPI-2 has been translated into many languages and is used in many different countries.

| Scale | Sample Item | What Is Assessed |

|---|---|---|

| ? (Cannot Say) | The score is the number of items that were unanswered or answered as both true and false. | An inability or unwillingness to complete the test appropriately, which could indicate the presence of symptoms that interfere with concentration. |

| L (Lie) | Sometimes want to swear (F) | Attempts to present himself or herself in a positive way, not admitting even minor shortcomings. |

| F (Infrequency) | Something wrong with mind (T) | Low scores suggest attempts to try to fake appearing to have “good” mental health or psychopathology; high scores suggest some type of psychopathology. |

| K (Correction) | Often feel useless (F) | More subtle attempts to exaggerate “good” mental health or psychopathology. This scale is also associated with education level—more educated people score higher than those with less education. |

| 1. Hs (Hypochondriasis) | Body tingles (F) | An abnormal concern over bodily functioning and imagined illness. |

| 2. D (Depression) | Usually happy (F) | Symptoms of sadness, poor morale, and hopelessness. |

| 3. Hy (Hysteria) | Often feel very weak (T) | A propensity to develop physical symptoms under stress, along with a lack of awareness and insight about one’s behavior. |

| 4. Pd (Psychopathic Deviate) | Am misunderstood (T) | General social maladjustment, irresponsibility, or lack of conscience. |

| 5. Mf (Masculinity–Femininity) | Like mechanics magazines (T for women) | The extent to which the individual has interests, preferences, and personal sensitivities more similar to those of the opposite sex. |

| 6. Pa (Paranoia) | No enemies who wish me harm (F) | Sensitivity to others, suspiciousness, jealousy, and moral self-righteousness. |

| 7. Pt (Psychasthenia) | Almost always anxious (T) | Obsessive and compulsive symptoms, poor concentration, and self-criticism. |

| 8. Sc (Schizophrenia) | Hear strange things when alone (T) | Delusions, hallucinations, bizarre sensory experiences, and poor social relationships. |

| 9. Ma (Hypomania) | When bored, stir things up (T) | Symptoms of hypomania—elated or irritable mood, “fast” thoughts, impulsiveness, and physical restlessness. |

| 10. Si (Social Introversion) | Try to avoid crowds (T) | Discomfort in social situations and preference for being alone. |

| Note: (T) indicates that when the item is marked as true, it contributes to a high score on the scale; (F) indicates that when the item is marked as false, it contributes to a high score on the scale. The dark green rows above refer to the validity scales, and the light green rows refer to the clinical scales. | ||

| Source: Excerpted from the MMPI-2 Booklet of Abbreviated Items. Copyright © 2005 by the Regents of the University of Minnesota. All rights reserved. Used by permission of the University of Minnesota Press. “MMPI-2” and “Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory 2” are trademarks owned by the Regents of the University of Minnesota. | ||

Projective test A tool for personality assessment in which the patient is presented with ambiguous stimuli (such as inkblots or stick figures) and is asked to make sense of and explain them.

Projective Tests Psychologists may also wish to assess facets of patients’ personalities that are less likely to emerge in a self-report, such as systematic biases in mental processes. In a projective test, the patient is presented with an ambiguous stimulus (such as an inkblot or a group of stick figures) and is asked to make sense of and explain the stimulus. For example, what does the inkblot look like, or what are the stick figures doing? The idea behind such a test is that the particular structure a patient imposes on the ambiguous stimulus reveals something about the patient’s mental processes or mental contents. This is the theory behind the well-known Rorschach test, which was developed by Herman Rorschach (1884–1922). This test includes 10 inkblots, one on each of 10 cards. The ambiguity of the shapes permits a patient to imagine what the shapes resemble. Although the Rorschach test may provide information about some aspects of a patient’s personality and mental functioning, it does not accurately assess most aspects of psychological disorders (Lilienfeld et al., 2000; Wood et al., 2001).

Another projective test, the Thematic Apperception Test (TAT), uses detailed black-and-white drawings that often include people. The TAT was developed by Christiana Morgan and Henry Murray (1935) and is used to discern motivations, thoughts, and feelings without having to ask a person directly. The patient is asked to explain the drawings in various ways: The clinician may ask the patient what is happening in the picture, what has just happened, what will happen next, or what the people in the picture might be thinking and feeling. Like the Rorschach test, the TAT elicits responses that presumably reflect unconscious beliefs, desires, fears, or issues (Murray, 1943). Responses on the TAT may be interpreted freely by the clinician or scored according to a scoring system. However, only 3% of clinicians who use the TAT rely on a scoring system (Pinkerman et al., 1993).

Assessing Social Factors

Symptoms arise in a context, and part of a thorough clinical assessment is collecting information about social factors. To some extent, the context helps the clinician or researcher understand the problems that initiated the assessment: How does the patient function in his or her home environment? Are there family factors or community factors that might influence treatment decisions? Is the patient from another culture, and if so, how might that affect the presentation of his or her symptoms or influence how the clinician should interpret other information obtained as part of the assessment?

The importance of social and environmental factors in making an assessment is illustrated by Arthur Kleinman (1988) in examples such as this: If a man has lost energy because he has contracted malaria, has a poor appetite as a result of anemia (due to a hookworm infestation), has insomnia as a result of chronic diarrhea, and he feels hopeless because of his poverty and powerlessness, does the person have depression? His symptoms meet the criteria for depression (as we shall see in Chapter 5), but isn’t his distress a result of his health problems and social circumstances and their consequences? Summing up his experiences as depression might limit our understanding of his situation and the best course of treatment.

Family Functioning

As noted in Chapter 2, various aspects of family functioning can affect a person’s mental health. This was certainly true of the Walls family, where Rex’s drinking and irresponsibility led Rose Mary to become overwhelmed and to “shut down”—staying in bed for days and crying. Similarly, their marriage appeared to have a role in Rex’s drinking problem (Walls, 2005).

In order to assess family functioning, clinicians may interview all or some family members or ask patients about how the family functions. Some clinicians and researchers try to assess family functioning more systematically than through interviews or observations. For example, the Family Environment Scale (Moos & Moos, 1986) requires family members to answer a set of questions. Their answers are integrated to create a profile of the family environment—how the family is organized, different types of control and conflict, family values, and emotional expressiveness. Such information helps the clinician or researcher to understand the patient within the context of his or her family and identifies possible areas of family functioning that could be improved (Ross & Hill, 2004).

Community

When making a clinical assessment, a clinician should try to learn about the patient’s community in order to understand what normal functioning is in that environment. As we saw in Chapter 2, people who have low socioeconomic status (SES) are more likely to have psychological disorders. These people live in poorer communities, which tend to have relatively high crime rates—and so they are more likely to witness a crime, be a victim of crime, or to live in fear. What, then, is “normal” functioning in this context?

In an effort to understand a patient within his or her social environment, “community” may be defined loosely; it can refer not only to where the patient lives but also to where he or she spends a lot of time, such as school or the workplace. Some jobs and work settings can be particularly stressful or challenging, and a comprehensive assessment should take such information about a patient into account. Consider that some work settings place very high demands on employees—high enough that some may become “burned out” (Aziz, 2004; Lindblom et al., 2006). Symptoms of burnout (a psychological condition, though not a psychological disorder in DSM-5) include feeling chronically mentally and physically tired, dissatisfied, and performing inefficiently—which resemble symptoms of depression (Maslach, 2003; Mausner-Dorsch & Eaton, 2000).

The clinician should also assess the patient’s capacity to manage daily life in his or her community, considering factors such as whether the patient’s psychological problems interfere with the sources for social support and ability to communicate his or her needs and interact with others in a relatively normal way. Similarly, the clinician may be asked to determine whether the patient would benefit from training to enhance his or her social skills (Combs et al., 2008).

Culture

To assess someone’s reports of distress or impairment, a clinician must understand the person’s culture. Different cultures have different views about complaining and how to describe different types of distress or other symptoms, which influence the amount and type of symptoms people will report to a mental health clinician—which, in turn, can affect the diagnosis a clinician makes. For instance, White British teenagers with anorexia nervosa say they are afraid of becoming fat and report being preoccupied with their weight (both symptoms are part of the criteria set for anorexia); in contrast, British teenagers of South Asian background do not report these symptoms but are more likely to report a loss of appetite (which is not part of the criteria set; Tareen et al., 2005). Thus, the reported symptoms of the British teenagers of South Asian background may not meet enough of the criteria for a diagnosis of anorexia—although they may still have significant distress, impairment, or risk of harm.

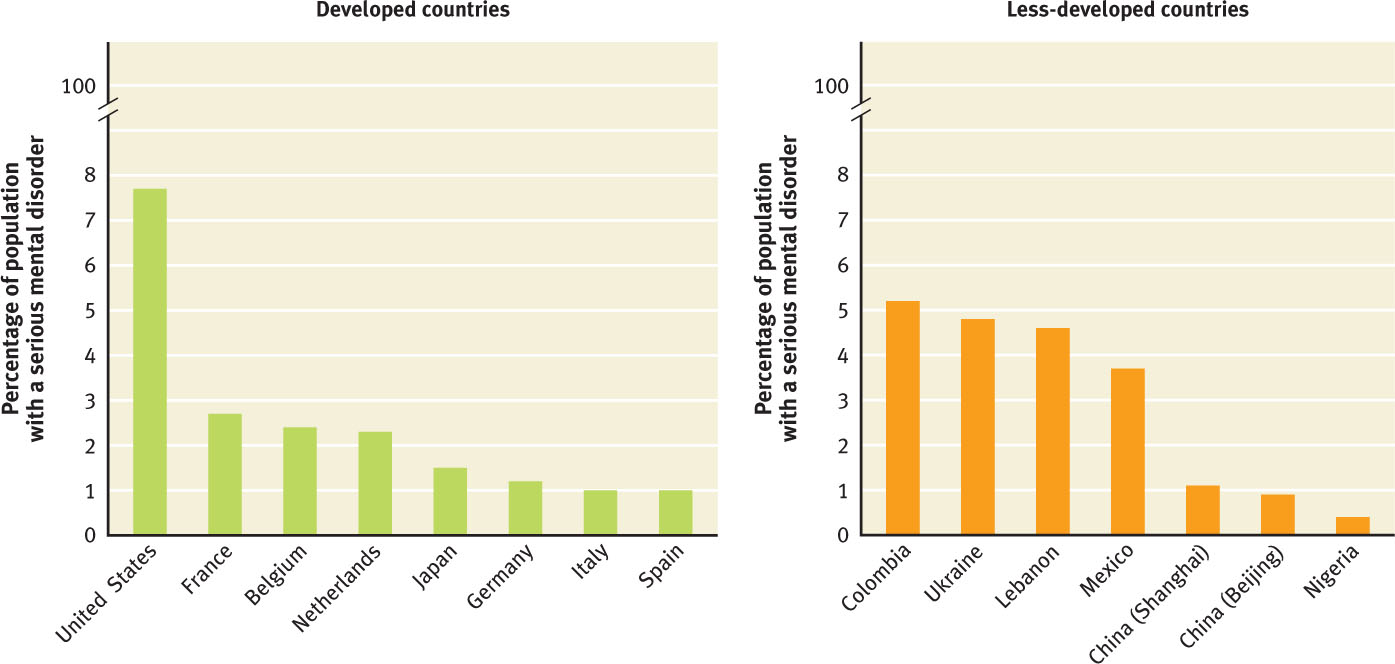

Such cultural differences may underlie, at least in part, the dramatic differences in the apparent rates of serious mental illness across countries, shown in Figure 3.3 (WHO World Mental Health Survey Consortium, 2004). (A mental illness was considered serious if the individual was unable to carry out his or her normal activities for at least 30 days in the past year.) These rates were based on data gathered in face-to-face interviews. Notice how much higher the rates are in the United States than in other developed and developing countries. One explanation for this discrepancy is that Americans are less inhibited about telling strangers about their psychological problems. People in other countries might have minimized the frequency or severity of their symptoms.

To help clinicians assess cultural factors, DSM-5 includes a 16-question Cultural Formulation Interview. Specifically, responses to this set of questions help clinicians to understand how culture and cultural identity might influence the ways that patients explain and understand their problems. These factors, in turn, may influence diagnosis and treatment (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Assessment as an Interactive Process

Mental health researchers and clinicians learn about patients from assessing psychological and social factors and, to a lesser extent, neurological and other biological factors. Information about each type of factor should not be considered in isolation but rather should influence how the clinician understands the other types of information.

Knowledge of psychological factors must be developed in the context of the patient’s culture. Psychiatrist Paul Linde (2002) recounts his experiences working in a psychiatric unit in Zimbabwe: The residents of that country generally understand that bacteria can cause an illness such as pneumonia, but they nonetheless wonder why the bacteria struck a particular individual at a specific point in time (a question that contemporary science is just beginning to try to answer). They look to ancestral spirits for an answer to such a question, even when a particular person is beset with mental rather than physical symptoms. In Zimbabwe, the first experience of hallucinations and delusions is viewed as a sign that the individual is being called to become a healer, a n’anga, and not as an indicator of mental illness.

Thus, knowledge of the patient’s culture influences how an outside researcher such as Linde understands the symptoms. When a patient in Zimbabwe claims to be hearing voices of dead ancestors, Linde undoubtedly interprets this symptom somewhat differently than he would if a White, American-born patient made the same claim. At the same time, knowledge of a patient’s family history of chronic schizophrenia (which may indicate a neurological factor—genetic, in this case) will also influence the interpretation of the patient’s symptoms.

Clearly, the way that each type of factor is assessed can influence how the other types of factors are assessed. However, comprehensive assessment of all three factors in the same patient is rarely undertaken. Formal testing beyond a brief questionnaire that the patient completes independently can be relatively expensive, and often health insurance companies will not pay for routine assessments; they will pay only for specific assessment procedures or tests that they have authorized in advance, based on indications of clear need (Eisman et al., 2000). Beyond an interview, other forms of assessment are most likely to be administered as part of a legal proceeding (e.g., a custody hearing or sentencing determination) or as part of a research project related to psychological disorders and their treatment.

Thinking Like A Clinician

Suppose that you have decided to become a mental health professional. What type of training (and what type of degree) would you obtain, and why?

Now suppose that you are working in an emergency room, assessing possible mental illness in patients. You have been asked to determine whether a 55-year-old woman, who was brought in by her son, has a psychological disorder severe enough for her to be hospitalized. Based on what you have read, if you could use only one assessment method of each type (neurological, psychological, and social), what methods would you choose, and why?