5.2 Bipolar Disorders

After receiving her Ph.D. in psychology and joining the faculty of the Department of Psychiatry at UCLA, Kay Jamison went to a garden party for faculty. The man who would later become her psychiatrist was there, and years later they discussed the party. Jamison’s memory of the party was that she was confident and alluring; in contrast, he remembered her as:

…dressed in a remarkably provocative way, totally unlike the conservative manner in which he had seen me dressed over the preceding year. I had on much more makeup than usual and seemed, to him, to be frenetic and far too talkative. He says he remembers having thought to himself, Kay looks manic. I, on the other hand, had thought I was splendid.

Bipolar disorders Mood disorders in which a person’s mood is often persistently and abnormally upbeat or shifts inappropriately from upbeat to markedly down.

The other set of mood disorders is Bipolar disorders—in which a person’s mood is often persistently and abnormally upbeat or shifts inappropriately from upbeat to markedly down. (Bipolar disorders were previously referred to as manic-depressive illness or simply manic depression.) Jamison’s behavior at the garden party indicates the opposite of depression—mania.

Mood Episodes for Bipolar Disorders

Diagnoses of bipolar disorders are based on three types of mood episodes. These three types are major depressive episode (which underlies MDD), manic episode, and hypomanic episode. The patterns of a person’s particular mood episodes determines not only the diagnosis but also the treatment and prognosis.

Manic Episode

Manic episode A period of at least 1 week characterized by abnormally increased energy or activity and abnormal and persistent euphoria or expansive mood or irritability.

The hallmark of a Manic episode, such as the one Jamison apparently had when at the garden party, is a discrete period of at least 1 week of abnormally increased energy or activity and abnormally euphoric feelings, intense irritability, or an expansive mood. During an Expansive mood, the person exhibits unceasing, indiscriminate enthusiasm for interpersonal or sexual interactions or for projects. The expansive mood and related behaviors contrast with the person’s usual state. For instance, a normally shy person may have extensive intimate conversations with strangers in public places during a manic episode. For some, though, the predominant mood during a manic episode may be irritability. Alternatively, during a manic episode, a person’s mood can shift between abnormal and persistent euphoria and irritability, as it did for Jamison:

Expansive mood A mood that involves unceasing, indiscriminate enthusiasm for interpersonal or sexual interactions or for projects.

When you’re high, it’s tremendous. The ideas and feelings are fast and frequent like shooting stars, and you follow them until you find better and brighter ones. Shyness goes, the right words and gestures are suddenly there, the power to captivate others a felt certainty…Sensuality is pervasive and the desire to seduce and be seduced irresistible. Feelings of ease, intensity, power, well-being, financial omnipotence, and euphoria pervade one’s marrow. But, somewhere, this changes. The fast ideas are far too fast, and there are far too many; overwhelming confusion replaces clarity. Memory goes. Humor and absorption on friends’ faces are replaced by fear and concerns. Everything previously moving with the grain is now against—you are irritable, angry, frightened, uncontrollable, and enmeshed totally in the blackest caves of the mind…It will never end, for madness carves its own reality. (1995

TABLE 5.6 lists the criteria for a manic episode.

|

| Reprinted with permission from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, (Copyright ©2013). American Psychiatric Association. All Rights Reserved. |

As noted in TABLE 5.6, during a manic episode, a person may begin projects that he or she doesn’t have the special knowledge or training to complete; for instance, the person might try to install a dishwasher, despite knowing nothing about plumbing. Moreover, when manic, some people are uncritically grandiose—often believing themselves to have superior abilities or a special relationship to political or entertainment figures; these beliefs may reach delusional proportions, to the point where a person may stalk a celebrity, believing that he or she is destined to marry that famous person.

Flight of ideas Thoughts that race faster than they can be said.

During a manic episode, a person needs much less sleep—so much less that he or she may be able to go days without it, or sleep only a few hours nightly, yet not feel tired. Similarly, when manic, the affected person may speak rapidly or loudly and may be difficult to interrupt; he or she may talk nonstop for hours on end, not letting anyone else get a word in edgewise. Moreover, when manic, the person rarely sits still (Cassano et al., 2009). Another symptom of mania is a Flight of ideas—thoughts that race faster than they can be said. When speaking while in this state of mind, the person may flit from topic to topic; flight of ideas has commonly been described by patients as something like watching two or three television programs simultaneously.

During a manic episode, the person may also be highly distractible and unable to screen out irrelevant details in the environment or in conversations. Another symptom of a manic episode is excessive planning of, and participation in, multiple activities. A college student with this symptom might participate in eight time-intensive extracurricular activities, including a theatrical production, a musical performance, a community service group, and a leadership position in a campus political group. The expansiveness, unwarranted optimism, grandiosity, and poor judgment of a manic episode can lead to the reckless pursuit of pleasurable activities, such as spending sprees or unusual sexual behavior (such as infidelity or indiscriminate sexual encounters with strangers). These activities often lead to adverse consequences: credit card debt from the spending sprees or sexually transmitted diseases, including HIV, from unprotected sex.

People who have had a manic episode report afterward that they felt as if their senses were sharper during the episode—that their ability to smell or hear was better. People often don’t recognize that they’re ill during a manic phase; this was the case with Jamison, who, for many years, resisted getting treatment.

Typically, a manic episode begins suddenly, with symptoms escalating rapidly over a few days; symptoms can last from a few weeks to several months. Compared to an MDE, a manic episode is briefer and ends more abruptly.

Hypomanic Episode

The last type of mood episode associated with bipolar disorders is a hypomanic episode, which has the same criteria as a manic episode, with two significant differences: The symptoms (1) don’t impair functioning, require hospitalization, or have psychotic features; and (2) they last a minimum of 4 days, not 1 week. Hypomania rarely includes the flight of ideas that bedevils someone in the grips of mania (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). In contrast to the grandiose thoughts people have about themselves during manic episodes, during hypomanic episodes people are uncritically self-confident but not grandiose. When hypomanic, some people may be more efficient and creative than they typically are (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). During a hypomanic episode, people may tend to talk loudly and rapidly, but, unlike when people are manic, it is possible to interrupt them.

The Two Types of Bipolar Disorder

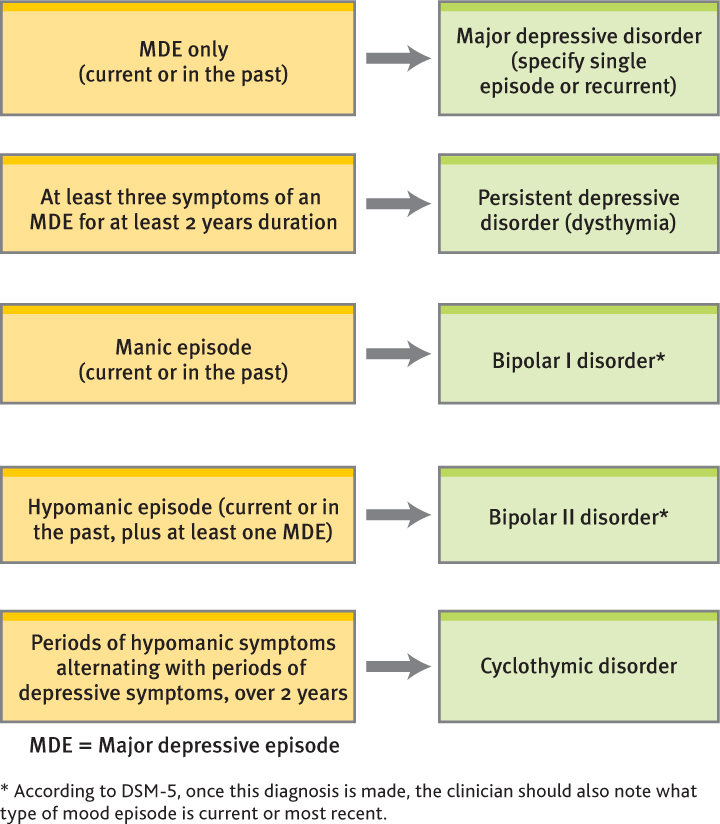

The presence of different types of mood episodes leads to different diagnoses. According to DSM-5, there are two types of bipolar disorder: bipolar I disorder and bipolar II disorder. Another disorder—cyclothymia (discussed shortly)—is characterized by symptoms of hypomania and depression that do not meet the criteria for either of the two types of bipolar disorder.

The presence of manic symptoms—but not a manic episode—is the common element of the two types of bipolar disorder. The types differ in the severity of the manic symptoms. To receive the diagnosis of the more severe bipolar I disorder, a person must have a manic episode; an MDE may also occur with bipolar I. Thus, just as an MDE automatically leads to a diagnosis of MDD, having a manic episode automatically leads to a diagnosis of bipolar I. Writer and actor Carrie Fisher, who suffers from bipolar disorder I, describes her experience in Case 5.4.

CASE 5.4 • FROM THE INSIDE: Bipolar Disorder

“I never shut up,” she says of the times her mania would start to take over. “I could be brilliant. I never had to look long for a word, a thought, a connection, a joke, anything.” Such heady feelings never lasted, though.

“I’d keep people on the phone for eight hours. When my mania is going strong, it’s sort of a clear path. You know, I’m flying high up onto the mountain, but it starts going too fast.”

“I stop being able to connect. My sentences don’t make sense. I’m not tracking anymore and I can’t sleep and I’m not reliable.”

(Staba, 2004)

In contrast, to be diagnosed with bipolar II disorder, a person must alternate between hypomanic episodes and MDEs (see TABLE 5.7); bipolar II can be thought of as less severe because of the absence of manic episodes; however, the unpredictable changes in mood and the depressive episodes can impair a person’s functioning. TABLE 5.8 provides additional facts about bipolar disorders.

|

| Source: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2013. |

| Prevalence |

|

| Onset |

|

| Comorbidity |

|

| Course |

|

| Gender Differences |

|

| Cultural Differences |

|

| Source: Unless otherwise noted, the source for information is American Psychiatric Association, 2013. |

Rapid cycling (of moods) Having four or more episodes that meet the criteria for any type of mood episode within 1 year.

Both types of bipolar disorder can include rapid cycling of moods, defined as having four or more of any type of mood episode within 1 year (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Rapid cycling is most common with bipolar II disorder and in women (Papadimitriou et al., 2005). Rapid cycling of either type of bipolar disorder is associated with difficulty finding an effective treatment (Ozcan et al., 2006). As with MDD, people with bipolar disorders may experience psychotic symptoms. People of different races and ethnicities are equally likely to be afflicted with bipolar disorders, just as with depression. Some mental health clinicians, however, tend to diagnose schizophrenia instead of a bipolar disorder when evaluating Black patients (Neighbors et al., 2003).

From Jamison’s descriptions, some of her experiences, such as those at the faculty garden party, appear to have been manic episodes. Because she had at least one manic episode, Jamison would be diagnosed with bipolar I disorder, thus changing from the tentative diagnosis of MDD proposed earlier in the chapter.

Cyclothymic Disorder

Cyclothymic disorder A mood disorder characterized by chronic, fluctuating mood disturbance with numerous periods of hypomanic symptoms alternating with depressive symptoms, each of which does not meet the criteria for its respective mood episodes.

Just as persistent depressive disorder is a more chronic but typically less intense version of MDD, cyclothymia is a more chronic but less intense version of bipolar II disorder. The main feature of Cyclothymic disorder is a chronic, fluctuating mood disturbance with numerous periods of hypomanic symptoms that alternate with depressive symptoms, each of which does not meet the criteria for its respective mood episodes. These symptoms have been present for at least half of the time within a 2-year period and have not completely disappeared for more than 2 consecutive months (see TABLE 5.9). Cyclothymia has a lifetime prevalence of 0.4–1.0% and affects men and women equally often (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Some people may function particularly well during the hypomanic periods of cyclothymic disorder but be impaired during depressive periods; this diagnosis is given only if the person’s depressed mood leads him or her to be distressed or impaired. Thus, someone with cyclothymic disorder may feel upbeat and energetic when having symptoms of hypomania and may begin several projects at work or complete projects ahead of schedule. However, when having symptoms of depression, he or she may have difficulty concentrating or mustering the energy to work on the projects and so may fall behind on the deadlines.

|

| Reprinted with permission from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, (Copyright ©2013). American Psychiatric Association. All Rights Reserved. |

Cyclothymia usually unfolds slowly during early adolescence or young adulthood, and it has a chronic course, as Mr. F’s history reveals (see Case 5.5). Approximately 15–50% of people with cyclothymia go on to develop bipolar disorder (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

CASE 5.5 • FROM THE OUTSIDE: Cyclothymic Disorder

At his girlfriend’s insistence, Mr. F., a 27-year-old single man, goes for a psychiatric evaluation. Mr. F. reports that he is excessively energetic, unable to sleep, and irritable, and he isn’t satisfied with the humdrum nature of his work and personal life. He is often dissatisfied and irritable for periods of time ranging from a few days to a few weeks. These periods alternate with longer periods of feeling dejected, hopeless, worn out, and wanting to die; his moods can shift up to 20–30 times each year, and he describes himself as on an “emotional roller-coaster” and has been for as long as he can remember. He twice impulsively tried to commit suicide with alcohol and sleeping pills, although he has never had prominent vegetative symptoms, nor has he had psychotic symptoms.

(Adapted from Frances & Ross, 1996, p. 140)

Because Jamison had both MDEs and manic episodes, her symptoms do not meet the criteria for cyclothymic disorder. Figure 5.4 identifies the various mood episodes and the corresponding mood disorders.

Understanding Bipolar Disorders

Kay Jamison made her professional life into a quest to understand mood disorders and why some people develop them. In the following sections we examine what is known about bipolar disorders using the neuropsychosocial approach.

Neurological Factors

As with depressive disorders, both distinctive brain functioning and genetics are associated with bipolar disorders.

Brain Systems

One hint about a neurological factor that may contribute to bipolar disorders is the finding that the amygdala is enlarged in people who have been diagnosed with a bipolar disorder (Altshuler et al., 1998). This finding is pertinent because the amygdala is involved in expressing emotion, as well as in governing mood and accessing emotional memories (LeDoux, 1996). Researchers have also found that the amygdala is more active in people who are experiencing a manic episode than it is in a control group of people who are not manic (Altshuler et al., 2005). The more reactive the amygdala, the more readily it triggers strong emotional reactions—and hence the fact that it is especially active during a manic episode makes sense.

Neural Communication

As we’ve discussed earlier in this chapter and in Chapter 2, imbalances in the levels of certain chemicals in the brain can contribute to psychological disorders. There’s reason to believe that serotonin (Goodwin & Jamison, 1990) and norepinephrine have roles in bipolar disorders. For example, treatment with lithium (discussed shortly) not only lowers norepinephrine levels but also reduces the symptoms of a bipolar disorder (Rosenbaum, Arana, et al., 2005). Serotonin is an inhibitory neurotransmitter, and low levels of it have been associated with depression (Mundo, Walker, et al., 2000). However, glitches in neural communication contribute to psychological disorders in complex ways; the problem rarely (if ever) is limited to an imbalance of a single substance but rather typically involves complex interactions among substances. In fact, researchers have also reported that the left frontal lobes of patients with mania produce too much of the excitatory neurotransmitter glutamate (Michael et al., 2003), so at least three neurotransmitters—serotonin, norepinephrine, and glutamate—are involved in bipolar disorders.

Genetics

Twin and adoption studies suggest that genes influence who will develop bipolar disorders. If one monozygotic twin has a bipolar disorder, the co-twin has a 40–70% chance of developing the disorder; if one dizygotic twin has the disorder, the co-twin has only about a 5% chance of developing the disorder, which is still over twice the prevalence in the population (Fridman et al., 2003; Kieseppä et al., 2004; McGuffin et al., 2003). In general, if you have a first-degree relative who has bipolar disorder, you have a 4–24% risk of developing the disorder (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Depressive disorders and bipolar disorders—even though they now are considered distinct disorders—in fact may be different manifestations of the same genetic vulnerability. When a dizygotic twin has a bipolar disorder, the other twin has an 80% chance of developing any mood disorder (MDD, persistent depressive disorder, a bipolar disorder, or cyclothymia) (Karkowski & Kendler, 1997; McGuffin et al., 2003; Vehmanen et al., 1995). Given such findings, it’s not surprising that Jamison had many relatives (on her father’s side) who had mood disorders. However, researchers do not yet know how specific genes contribute to an inherited vulnerability for mood disorders.

Psychological Factors: Thoughts and Attributions

Most research on the contribution of psychological factors to bipolar disorders focuses on cognitive distortions and automatic negative thoughts, which not only are common among people with depression but also plague people with a bipolar disorder during MDEs. In fact, research suggests that when depressed, people with either MDD or a bipolar disorder have a similar internal attributional style for negative events (Lyon et al., 1999; Scott et al., 2000). Mirroring these results, people with cyclothymia or persistent depressive disorder have a similar negative attributional style (Alloy et al., 1999).

In addition, even after a manic episode is completely resolved, up to one third of people may have residual cognitive deficits, ranging from difficulties with attention, learning, and memory to problems with executive functioning (planning and decision making) and problem solving (Kolur et al., 2006; Thompson et al., 2005; Zubieta et al., 2001). Moreover, the more mood episodes a person has, the more severe these deficits tend to be. Researchers propose that the persistent cognitive deficits associated with mania should become part of the diagnostic criteria for bipolar disorders, in addition to criteria on mood-related behaviors (Phillips & Frank, 2006).

Social Factors: Social and Environmental Stressors

Social factors such as starting a new job or moving to a different city can also affect the course of bipolar disorders (Goodwin & Jamison, 1990; Malkoff-Schwartz et al., 1998). Stress appears to be part of the process that leads to a first episode (Kessing et al., 2004); people who develop a bipolar disorder often experience significant stressors in their lives before their first episode (Goodwin & Ghaemi, 1998; Tsuchiya, Agerbo, et al., 2005). Stress can also worsen the course of the disorder (Johnson & Miller, 1997). In addition, stress—in particular, family-related stress—may contribute to relapse; people who live with family members who are critical of them are more likely to relapse than those whose family members are not critical (Honig et al., 1997; Miklowitz et al., 1988).

Social factors can also have indirect effects, such as occurs when a new job disrupts a person’s sleep pattern, which in turn triggers neurological factors that can lead to a mood episode.

Feedback Loops in Understanding Bipolar Disorders

ONLINE

Bipolar disorders have a clear genetic and neurological basis, but feedback loops nevertheless operate among the neurological, psychological, and social factors associated with these disorders. Consider the effects of sleep deprivation. It may directly or indirectly affect neurological functioning, making the person more vulnerable to a manic or depressive episode. Moreover, like people with depression, people with a bipolar disorder tend to have an attributional style (psychological factor) that may make them more vulnerable to becoming depressed. In turn, their attributional style may affect how these people interact with others (social factor), such as in the way they respond to problems in relationships. Even after a mood episode is over, residual problems with cognitive functioning—which affect problem solving, planning, or decision making—can adversely influence the work and social life of a person with a bipolar disorder.

We can now understand Jamison’s bipolar disorder as arising from a confluence of neuropsychosocial factors and feedback loops. Her family history provided a strong genetic component to her illness, which has a clear neurological basis (neurological factors). Her struggle against recognizing that she had an illness (psychological factors) meant that she didn’t do as good a job as she could have done in protecting herself from overwork (social factor), making her more vulnerable to a mood episode.

Treating Bipolar Disorders

As with depressive disorders, treatment for bipolar disorders can directly target any of the three types of factors—neurological, psychological, and social. Keep in mind, though, that the effects of any successful treatment extend to all the types of factors. Jamison describes the subtle ways that feedback loops operated on her disorder and treatment:

My temperament, moods, and illness clearly, and deeply, affected the relationships I had with others and the fabric of my work. But my moods were themselves powerfully shaped by the same relationships and work. The challenge was in learning to understand the complexity of this mutual beholdenness and in learning to distinguish the roles of [the medication] lithium, will, and insight in getting well and in leading a meaningful life. It was the task and gift of psychotherapy.

(1995, p. 88)

Targeting Neurological Factors: Medication

Mood stabilizer A category of medication that minimizes mood swings.

People diagnosed with a bipolar disorder usually take some type of Mood stabilizer—a medication that minimizes mood swings—for the rest of their lives. (The term mood stabilizer is sometimes used more broadly to include medications that decrease impulsive behavior and violent aggression.) Mood stabilizers can reduce recurrences of both manic and depressive episodes (Arana & Rosenbaum, 2000). The oldest mood stabilizer is Lithium; technically the medication is called lithium carbonate, a type of salt. Jamison describes her response to the drug: “I took [lithium] faithfully and found that life was a much stabler and more predictable place than I had ever reckoned. My moods were still intense and my temperament rather quick to the boil, but I could make plans with far more certainty and the periods of absolute blackness were fewer and less extreme” (1995. Lithium apparently affects several different neurotransmitters (Lenox & Hahn, 2000) and thereby alters the inner workings of neurons (Friedrich, 2005). However, too high a dose of lithium can produce severe side effects, including coordination problems, vomiting, muscular weakness, blurred vision, and ringing in the ears; thus, patients must have their blood levels of lithium checked regularly to ensure that they are taking an appropriate dosage (Arana & Rosenbaum, 2000).

Lithium The oldest mood stabilizer.

Lithium is not an effective treatment for all patients. In fact, up to half of patients who are prescribed lithium either cannot tolerate the side effects or do not show significant improvement, especially patients who have rapid cycling (Burgess et al., 2001; Keck & McElroy, 2003; Montgomery et al., 2001). In such cases, other mood stabilizers may help to prevent extreme mood shifts, especially recurring manic episodes. These include antiepileptic medications (also called anticonvulsants) such as divalproex (Depakote), carbamazepine (Tegretol), lamotrigine (Lamictal), and gabapentin (Neurontin).

Some people with bipolar disorders stop taking mood stabilizers not because of the common side effects (such as thirst, frequent urination, and diarrhea) but rather because the medication does what it’s supposed to do—evens out their moods (Arana & Rosenbaum, 2000; Rosa et al., 2007). Some of these people report that they miss aspects of their manic episodes and feel that the medication blunts their emotions.

Mood stabilizers aren’t the only medications given for bipolar disorders. Patients with a bipolar disorder may be given antidepressant medication for depression, but such medications can induce mania and so should be taken along with a mood stabilizer; in addition, patients with a bipolar disorder who take antidepressant medication should take it for as brief a period as possible (Rosenbaum, Arana, et al., 2005). For a manic episode, the person may be given an antipsychotic medication such as olanzapine (Zyprexa) or aripiprazole (Abilify) or a high dose of a benzodiazepine—a class of medications commonly known as tranquilizers (Keck et al., 2009; Yildiz et al., 2011).

Despite the number of medications available to treat bipolar disorders, mood episodes still recur; in one study, half of the participants developed a subsequent mood episode within 2 years of recovery from an earlier episode (Perlis, Ostacher, et al., 2006).

Targeting Psychological Factors: Thoughts, Moods, and Relapse Prevention

Medication can be an effective component of treatment for bipolar disorders, but often it isn’t the only component. Treatment that targets psychological factors focuses on helping patients develop patterns of thought and behavior that minimize the risk of relapse (Fava, Bartolucci, et al., 2001; Jones, 2004; Scott & Gutierrez, 2004). CBT can help patients stick with their medication schedules, develop better sleeping strategies, and recognize early signs of mood episodes, such as needing less sleep (Frank et al., 2005; Miklowitz, 2008; Miklowitz et al., 2007).

Targeting Social Factors: Interacting with Others

GETTING THE PICTURE

© CulturaCreative (RF)/Alamy

Treatments that target social factors are designed to help patients minimize disruptions in their social patterns and develop strategies for better social interactions (Lam et al., 2000), which can reduce the rate of relapse. One such treatment, adapted from IPT, is called interpersonal and social rhythm therapy (IPSRT; Frank et al., 1999). As in IPT, IPSRT sessions focus on identifying themes of social stressors, such as a relationship conflict that arises because partners have different expectations of the relationship. Treatment can then focus on developing effective ways for the patient to minimize such social stressors. In addition, IPSRT focuses on the timing of events (such as arranging weekend activities so that the patient wakes up at the same time each morning and goes to sleep at the same time each night—weekend and weekday), increasing overall regularity in daily life (such as having meals at relatively fixed times during the day), and helping the patient want to maintain regularity. IPSRT plus medication is more effective than medication alone (Miklowitz, 2008; Miklowitz et al., 2007).

Other treatments that target social factors focus on the family: educating family members about bipolar disorder and providing emergency counseling during crises (Miklowitz et al., 2000, 2003, 2007). Also, family therapy that leads family members to be less critical of the patient can reduce relapses (Honig et al., 1997). Another treatment with a social focus is group therapy or a self-help group, either of which can decrease the sense of isolation or shame that people with a bipolar disorder may experience; group members support each other as they try to make positive changes.

Feedback Loops in Treating Bipolar Disorder

Both Jamison and her psychiatrist understood that treatment could affect multiple factors. She recognized that medication might help her, but she had to want to take the medication. Similarly, she recognized that psychotherapy alone could not prevent her mood episodes. She needed them both.

ONLINE

We have seen that successful treatments for bipolar disorders can address multiple factors—for example, CBT can result in more consistent medication use, and IPSRT can reduce the frequency of events that might trigger relapse. Successful treatment can also affect interpersonal relationships, leading patients to interact differently with others, develop a more regular schedule, and come to view themselves differently. Moreover, such therapy leads patients to change the attributions they make about events and even change how reliably they take medication for the disorder.

Jamison’s treatment involved interactions among the factors: Her therapy helped her to recognize and accept her illness and encouraged her to take care of herself more appropriately (psychological and social factors), including sticking with a daily regimen of lithium (neurological factor). Furthermore, the successful lithium treatment allowed her to have better relationships with others (social factor), which led to a positive change in how she saw herself (psychological factor).

Thinking Like A Clinician

You get in touch with a friend from high school who tells you that she recently had experiences that you realize are symptoms of hypomania. What are two possible DSM-5 diagnoses that might apply to her? (Be specific.) What will determine which diagnosis is most appropriate? What are a few of the symptoms that are hallmarks of hypomania? What would be the difference in symptoms if your friend instead experienced a manic episode? Would her diagnosis change or stay the same? Explain. What would be the most appropriate ways to treat bipolar disorders?