6.2 Generalized Anxiety Disorder

Earl Campbell became a worrier—even during the best of times:

On a day when life seems absolutely wonderful—say, a beautiful fall Saturday or Sunday when I’m watching one of my boys play football—I’ll often be overcome by the fear that it will all come to an end somehow. It’s just too good. Something bad is going to ruin it for me. This past year was the most difficult one I’ve had…. Tyler [his son] was in the fifth grade, and I worried the entire year. I was in the fifth grade when my father died, and I thought my fate was sealed. I was scared I would die and my boys would have to go through life without a father, the way I did.

(Campbell & Ruane, 1999, p. 204)

Worrying is a normal part of life, and some people worry more than others. But how much is “too much” worrying?

What Is Generalized Anxiety Disorder?

Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) An anxiety disorder characterized by uncontrollable worry and anxiety about a number of events or activities, which are not solely the result of another disorder.

Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) is characterized by excessive and persistent worry and anxiety about a number of events or activities (which are not solely the focus of another disorder, such as worrying about having a panic attack) (see TABLE 6.1; American Psychiatric Association, 2013). For people suffering from GAD, the worry and anxiety focus primarily on family, finances, work, and illness (Sanderson & Barlow, 1990), and—given the actual extent of the problem with family, finances, work, or illness—the person’s worries are excessive (as determined by the mental health clinician). Earl Campbell worried mostly about family and illness; other people may worry about minor matters (Craske et al., 1989). In contrast to most other people, people with GAD worry even when things are going well. Moreover, their worries intrude into their awareness when they are trying to focus on other thoughts, and they lead people to feel on edge or have muscle tension (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Like A. H., discussed in Case 6.1, people with GAD feel a chronic, low level of anxiety or worry about many things. Moreover, the fact that they constantly worry in itself causes them distress.

|

| Reprinted with permission from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, (Copyright ©2013). American Psychiatric Association. All Rights Reserved. |

CASE 6.1 • FROM THE OUTSIDE: Generalized Anxiety Disorder

A. H. was a 39-year-old divorced mother of two (son aged 12, daughter aged 7) who worked as a bank manager. However, she had become concerned about her ability to concentrate on and remember information while at work. A. H. had made some “financially disastrous” mistakes and was now—at the suggestion of her supervisor—taking some vacation time to “get her head together.” Because of her concentration and memory problems, it had been taking her longer to complete her work, so she had been arriving at work 30 minutes early each day, and she often took work home. She reported being unable to relax, even outside of work, and at work it was hard to make decisions because she ruminated endlessly (“Is this the right decision, or should I do that?”) and hence tried to avoid making decisions altogether. Her concentration and memory problems were worst when she was worried about some aspect of life, which was most of the time. She reported that 75% of her waking life each day was spent in a state of anxiety and worry. In addition to worrying about her performance at work, she worried about her children’s well-being (whether they had been hurt or killed while out playing in the neighborhood). She also worried about her relationships with men and minor things such as getting to work on time, keeping her house clean, and maintaining regular contact with friends and family. A. H. recognized that her fears were both excessive and uncontrollable, but she couldn’t dismiss any worry that came to mind. She was irritable, had insomnia, had frequent muscle tension and headaches, and felt generally on edge.

(Adapted from Brown & Barlow, 1997, pp. 1–3)

Because the symptoms are chronic (lasting at least 6 months) and because many people with GAD can usually function adequately in some areas of their daily lives, they come to see their worrying and anxiety as a part of themselves, not as a disorder. However, the intrusive worrying can lead to problems in work and social life. See TABLE 6.2 for more facts about GAD.

| Prevalence |

|

| Comorbidity |

|

| Onset |

|

| Course |

|

| Gender Differences |

|

| Cultural Differences |

|

| Source: Unless otherwise noted, the source for information is American Psychiatric Association, 2013 |

As noted in TABLE 6.2, GAD and depression have an extremely high comorbidity. Among people who have both disorders at the same time, only 27% eventually experience remission, compared to 48% of those who have only GAD and 41% of those who have only depression (Schoevers et al., 2005). People with both disorders are also likely to have had their symptoms arise at a younger age, to have more severe symptoms of each disorder, and to function less well than those who have only one of the two disorders (Moffitt et al., 2007; Zimmerman & Chelminski, 2003). The high comorbidity also suggests that GAD and depression may reflect different facets of the same underlying problem, which is rooted in distress, worry, and the continued intrusion of negative thoughts (Ruscio et al., 2011; Schoevers et al., 2003).

Understanding Generalized Anxiety Disorder

GAD can be best understood by using the neuropsychosocial approach to examine its etiology—by considering neurological, psychological, and social factors and the feedback loops among them. Each type of factor, by itself, seems to be necessary but not sufficient to give rise to this disorder. It may be best to conceive of neurological and psychological factors as setting the stage, and social factors as triggering the symptoms.

Neurological Factors

The parasympathetic nervous system appears to play a special role in GAD, a complex mix of neurotransmitters is involved in the disorder, and genetics can predispose someone to develop GAD.

Brain Systems

Unlike most other types of anxiety disorders, GAD isn’t associated with the cranked-up sympathetic nervous system activity that underlies the fight-or-flight response (Marten et al., 1993). Instead, GAD is associated with decreased arousal that arises from an unusually responsive parasympathetic nervous system. The parasympathetic nervous system tends to cause effects opposite those caused by the sympathetic nervous system. So, for instance, heightened parasympathetic activity slows heart rate, stimulates digestion and the bladder, and causes pupils to contract (Barlow, 2002a). When a person with GAD perceives a threatening stimulus, his or her subsequent worry temporarily reduces arousal (Borkovec & Hu, 1990), suppresses negative emotions (see Figure 6.1), and produces muscle tension (Barlow, 2002a; Pluess et al., 2009). These facts are in stark contrast to Earl Campbell’s symptoms, which suggest that he did not have GAD.

Neural Communication

Although the frontal lobes of patients with GAD are normal in size, the dopamine in the frontal lobes of these patients does not function normally (Stein, Westenberg, & Liebowitz, 2002). In fact, numerous studies suggest that a wide range of neurotransmitters, including gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), serotonin, and norepinephrine, may not function properly in people with GAD (Nutt, 2001). These neurotransmitters affect, among other things, people’s response to reward, their motivation, and how effectively they can pay attention to stimuli and events.

Genetics

Studies of the genetics of GAD have produced solid evidence that GAD has a genetic component, and the disorder is equally heritable for men and women (Hettema, Prescott, & Kendler, 2001). However, if one family member has GAD, other family members are likely to have GAD or depression, which suggests a common underlying genetic vulnerability (Gorwood, 2004; Kendler et al., 2007).

Psychological Factors: Hypervigilance and the Illusion of Control

Hypervigilance A heightened search for threats.

Psychological factors that contribute to GAD generally involve three characteristic modes of thinking and behaving:

- People with GAD pay a lot of attention to stimuli in their environment, searching for possible threats. This heightened search for threats is called hypervigilance.

- People with GAD typically feel that their worries are out of control and that they can’t stop or alter the pattern of their thoughts, no matter what they do.

- The mere act of worrying prevents anxiety from becoming panic (Craske, 1999), and thus the act of worrying is negatively reinforcing (Borkovec, 1994a; Borkovec et al., 1999). The worrying does not help the person to cope with the problem at hand, but it does give him or her the illusion of coping, which temporarily decreases anxiety about the perceived threat. Some people think that if they worry, they are actively addressing a problem. But they are not—-worrying is not the same thing as effective problem solving; the original concern isn’t reduced by the worrying, and it remains a problem, along with the additional problem of chronic worrying.

Social Factors: Stressors

Stressful life events—such as a death in the family, friction in a close relationship, or trouble on the job—can trigger symptoms of GAD in someone who is neurologically and psychologically vulnerable to developing it. For people who develop GAD after age 40, the disorder often arises after the person experiences a significant stressor.

GAD also appears to be related more directly to relationships. People with GAD may experience increased stress if they view themselves as having serious problems in relationships. Increased stress, in turn, can lead to distress and negative emotions that can be difficult to manage and regulate (Mennin et al., 2004).

Feedback Loops in Understanding Generalized Anxiety Disorder

ONLINE

Stressful life experiences (typically social factors) can trigger the onset of GAD, but most people who experience stressful periods in their lives—even extreme stress—never develop this disorder. Moreover, people who develop GAD often report that they were afraid and avoidant as children (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), which may be explained by abnormal neurological functioning. However, such abnormal functioning in childhood could arise from genes, might develop in childhood because of early life experiences, or could be caused by some combination of the two. To develop GAD, a person probably must have abnormal neurological functioning (which may reflect abnormal levels of GABA or another neurotransmitter), have learned certain kinds of worry-related behaviors such as hypervigilance for threats, and have experienced a highly stressful event or set of events such as a death in the family. Any one of these alone—and probably any two of these—will not cause GAD.

Treating Generalized Anxiety Disorder

Treatment for GAD can target neurological, psychological, or social factors, but neurological or psychological factors are the predominant focus of treatments. As usual, interventions targeting any one type of factor have ripple effects that in turn alter the other types of factors.

Targeting Neurological Factors: Medication

The antianxiety medication buspirone (Buspar) effectively reduces the symptoms of GAD, probably by decreasing serotonin release. Serotonin facilitates changes in the amygdala that underlie learning to fear objects or situations (Huang & Kandel, 2007); thus, reducing serotonin may impair learning to fear or worry about specific objects or situations.

Most people with GAD are also depressed, but buspirone only helps anxiety symptoms (Davidson, 2001). In contrast, the serotonin/norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) venlafaxine (Effexor) and certain selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), such as paroxetine (Paxil) and escitalopram (Lexapro), appear to relieve both anxiety and depressive symptoms (Baldwin & Polkinghorn, 2005; Davidson, 2001). This is why an SNRI is considered the “first-line medication” for people with both GAD and depression, meaning that it is the medication that clinicians try first with these patients (unless there is a reason not to use it).

Targeting Psychological Factors

Psychological treatments for GAD generally have several aims:

- to increase the person’s sense of control over thoughts and worries,

- to allow the person to assess more accurately how likely and dangerous perceived threats actually are, and

- to decrease muscle tension.

Psychotherapy for GAD generally consists of behavioral and cognitive methods, which can successfully decrease symptoms (Cottraux, 2004; Durham et al., 2003; Hanrahan et al., 2013).

Behavioral Methods

Behavioral methods to treat GAD focus on three main areas (Barlow, 2002a):

- awareness and control of breathing,

- awareness and control of muscle tension and relaxation, and

- elimination, reduction, or prevention of worries and behaviors associated with worries.

Breathing retraining requires patients to become aware of their breathing and to try to control it by taking deep, relaxing breaths. Such breathing can help induce relaxation and provide a sense of coping—of doing something positive in response to worry.

Biofeedback A technique in which a person is trained to bring normally involuntary or unconscious bodily activity, such as heart rate or muscle tension, under voluntary control.

Similarly, muscle relaxation training requires patients to become aware of early signs of muscle tension, a symptom of GAD in some people, and then to relax those muscles. Patients can learn how to identify tense muscles and then relax them through standard relaxation techniques or biofeedback, a technique in which a person is trained to bring normally involuntary or unconscious bodily activity, such as heart rate or muscle tension, under voluntary control. Typically, electrodes are attached to a targeted muscle or group of muscles, and the patient can see on a monitor or hear from a speaker signals that indicate whether the monitored muscles are tense or relaxed. This feedback helps the patient learn how to detect and reduce the tension, eventually without relying on the feedback.

Habituation The process by which the emotional response to a stimulus that elicits fear or anxiety is reduced by exposing the patient to the stimulus repeatedly.

A common treatment for anxiety disorders, including GAD, is based on the principle of habituation: The emotional response to a stimulus that elicits fear or anxiety is reduced by exposing the patient to the stimulus repeatedly. The technique of exposure involves such repeated contact with the (feared or arousing) stimulus in a controlled setting, and usually in a gradual way, bringing about habituation. Exposure, and therefore habituation, to fear- or anxiety-related stimuli does not normally occur outside of therapy because people avoid the object or situation, thereby making exposure (and habituation) unlikely. In exposure-based treatment, the patient first creates a hierarchy of feared events, arranging them from least to most feared, and then begins the exposure process by having contact with the least-feared item on the hierarchy. With GAD, that might be addressing worries about possibly bouncing a check (lower in the hierarchy) to worries that if a spouse is late it is because he or she was in a car accident. With sustained exposure, the symptoms diminish within 20 to 30 minutes or less; that is, habituation to the fear- or anxiety-inducing stimuli occurs. Over multiple sessions, this process is repeated with items higher in the hierarchy (i.e., those that are more feared), until all items no longer elicit significant symptoms. Patients in therapy can experience exposure in three ways:

Exposure A behavioral technique that involves repeated contact with a feared or arousing stimulus in a controlled setting, bringing about habituation.

- imaginal exposure, which relies on forming mental images of the stimulus;

- virtual reality exposure, which consists of exposure to a computer-generated (often very realistic) representation of the stimulus; and

- in vivo exposure, which is direct exposure to the actual stimulus.

In vivo exposure A behavioral therapy method that consists of direct exposure to a feared or avoided situation or stimulus.

People with GAD often develop behaviors that are associated with their worries. For instance, a patient who worries that “something bad” may happen to her family may call home several times each day. By calling home and finding out that everyone is fine, she temporarily reduces her anxiety, thus (negatively) reinforcing the calling behavior. People with GAD do not naturally habituate to such anxiety; as they worry about one set of concerns, they get increasingly anxious until they shift the focus of their worry to another set of concerns, never becoming habituated to any specific set of concerns.

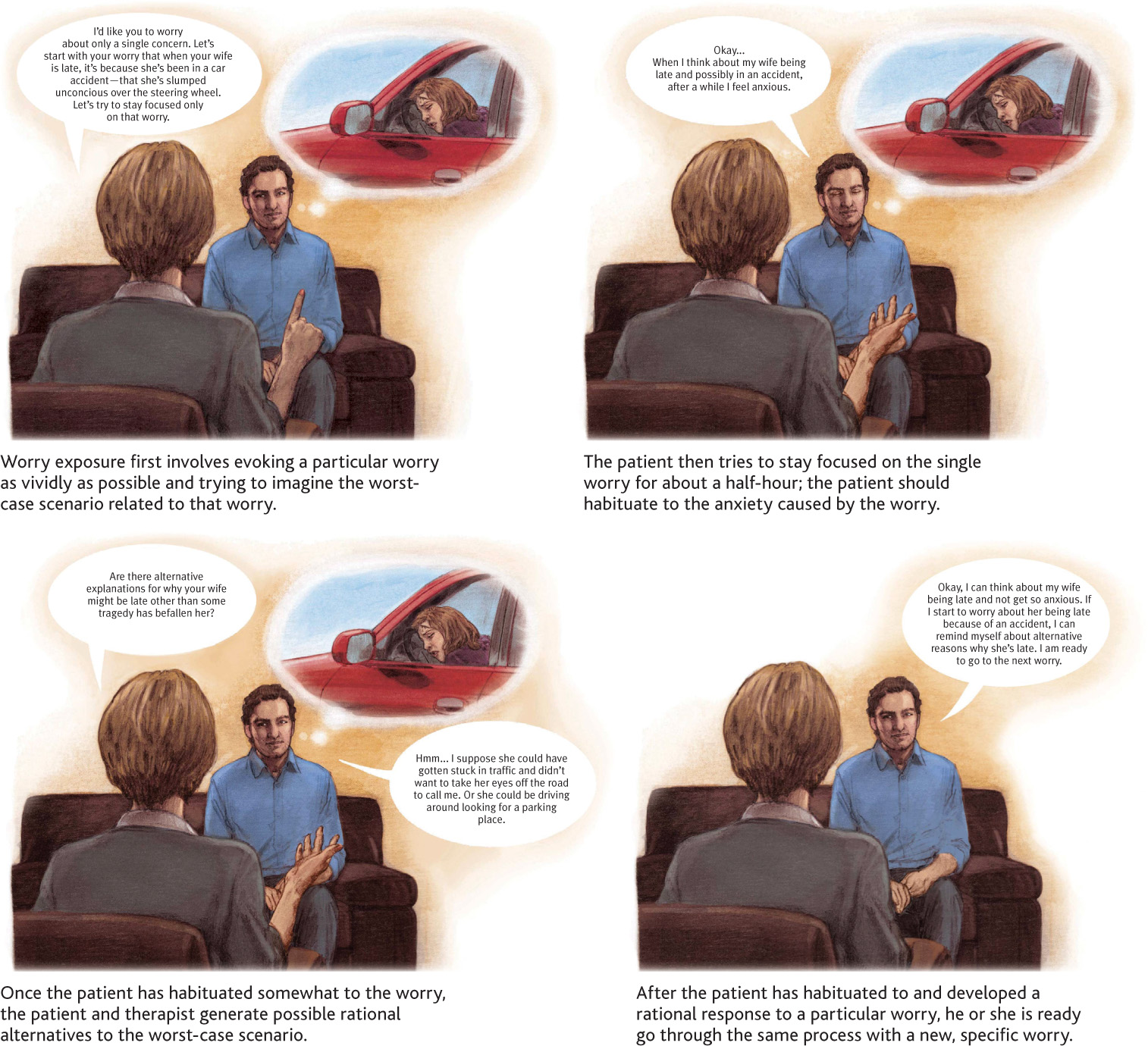

Using exposure to treat GAD, patients are asked to think about only one specific worry (this is the exposure) and to imagine their worst possible fears about the subject of that worry, such as the possible deaths of family members. Patients are asked to think about their worry continuously for about 30 minutes. After this half-hour of exposure, patients then list their rational responses to the worst outcomes they imagined. Patients’ anxiety and level of worry should decrease both over the course of the session and across sessions. When patients can think about one set of concerns without much worry or anxiety, they move on to use the same procedure with another set of concerns (see Figure 6.2).

Cognitive Methods

Cognitive methods for treating GAD focus on first helping patients to identify the thought patterns that are associated with their worries and anxieties and then helping them to use cognitive restructuring and other methods to prevent these thought patterns from spiraling out of control. The methods can also decrease the intensity of patients’ responses to their thought patterns, so that they are less likely to develop symptoms. Specific cognitive methods include the following:

- Psychoeducation, which is the process of educating patients about research findings and therapy procedures relevant to their situation. For patients with GAD, this means educating them about the nature of worrying and GAD symptoms and about available treatment options and their possible advantages and disadvantages.

Psychoeducation The process of educating patients about research findings and therapy procedures relevant to their situation.

- Meditation, which helps patients learn to “let go” of thoughts and reduce the time spent thinking about worries (Evans et al., 2008; Lehrer & Woolfolk, 1994; Miller et al., 1995).

- Self-monitoring, which helps patients become aware of cues that lead to anxiety and worry. For instance, patients may be asked to complete a daily log about their worries, identifying events or stimuli that lead them to worry more or worry less.

- Problem solving, which involves teaching the patient to think about worries in very specific terms—rather than global ones—so that they can be addressed through cognitive restructuring.

- Cognitive restructuring, which involves helping patients learn to identify and shift automatic, irrational thoughts related to worries (see the third panel in Figure 6.2).

Targeting Social Factors

The neuropsychosocial approach leads us to notice whether certain kinds of treatments are available for particular disorders. For instance, at present, there are very few treatments for GAD that specifically target social factors, and none of them have been successful enough to summarize here.

Feedback Loops in Treating Generalized Anxiety Disorder

ONLINE

When behavioral methods and cognitive methods are successful, the person develops a sense of mastery of and control over worries and anxiety (which decreases the worries and anxiety even further), and social interactions reinforce new behaviors. Similarly, medication directly targets neurological factors, which in turn reduces the person’s worries and anxiety; he or she becomes less preoccupied with these concerns, which increases the ability to focus at work and in relationships.

Did Earl Campbell develop GAD? Although his worries may seem excessive and uncontrollable at times, they do not appear to have had the effects necessary for the diagnosis, such as muscle tension, irritability, or difficulty sleeping. Any irritability or sleep problems he had are better explained as symptoms of another anxiety disorder—panic disorder, which we discuss in the following section.

Thinking Like A Clinician

Based on what you have read, what differentiates a “worrywart”—someone who worries a lot—from someone with GAD? If having GAD is distressing, why don’t patients simply stop worrying? What factors maintain the disorder? If someone you know with GAD asked you for advice about what kind of treatment to get, what would you recommend (based on what you have read) and why?