9.4 Other Abused Substances

This chapter has focused so far on stimulants and depressants because they are the most commonly abused substances. However, they are not the only substances that people abuse. In this section we briefly review three classes of other substances that are often abused: opioids (such as codeine and heroin), hallucinogens (such as marijuana), and dissociative anesthetics (such as ketamine).

What Are Other Abused Substances?

By 1969, the Beatles had not performed for 3 years. In that year, they agreed to perform and have their rehearsals filmed. They spent a month in a recording studio, composing and arranging songs, learning their parts, and rehearsing the songs. Rather than a true concert, however, the project culminated in a live, rooftop performance that was filmed. Some of this arduous process and the final concert were captured in the film Let It Be, which shows glimpses of the effects of John Lennon’s heroin use. Lennon had difficulty remembering song lyrics from hour to hour and day to day, had trouble getting up each morning and arriving at the sessions on time, and had difficulty concentrating on writing and finishing songs (Spitz, 2005; Sulpy & Schweighardt, 1994). Such problems are typical of heroin use in particular and of the use of opioids more generally.

Opioids: Narcotic Analgesics

Opioids— also called opiates or narcotic analgesics—are derived from the opium poppy plant or chemically related substances. These substances are perhaps best characterized as exogenous opioids (exogenous means “arising from an outside source”). Exogenous opioids include methadone and heroin (to be discussed in more detail shortly), as well as codeine, morphine, and synthetic derivatives found in prescription pain relief medications such as oxycodone (OxyContin), hydrocodone (Vicodin), and others. Legal but restricted narcotic analgesics are generally prescribed for persistent coughing, severe diarrhea, and severe pain. These drugs can be injected, snorted, or taken by mouth.

All analgesics relieve pain, and people who take analgesics for recreational purposes may temporarily experience pleasant, relaxing effects. However, this category of drugs is highly addictive: Their use rapidly leads to tolerance and withdrawal and compulsive behavior related to procuring and taking the drug. Although users may experience euphoria after taking such a drug, that mood fades to apathy, unhappiness, impaired judgment, and psychomotor agitation (the “fidgets”) or psychomotor retardation (sluggishness). Users may also experience confusion—as happened to John Lennon—as well as slurred speech, sedation, or unconsciousness. Narcotics depress the central nervous system and can cause drowsiness and slower breathing, which can lead to death if an opioid is taken with a depressant.

Withdrawal from an opioid typically begins within 8 hours after the drug was last used and peaks within several days. Physical symptoms of withdrawal include nausea and vomiting, muscle aches, dilated pupils, sweating, fever, and diarrhea; many of the symptoms are similar to those of a bad case of the flu. Depressed mood, irritability, and a sense of restlessness are also common during withdrawal.

Heroin is one of the stronger opioids and is very addictive. The contrast between the euphoria that the drug induces and the letdown that comes when its effects wear off can drive some people to crave the euphoria, and so they take the drug, again and again—which in turn leads to tolerance. Tolerance makes the same dose of heroin fall short: Instead of causing euphoria, it often causes irritability (NIDA, 2007c).

Surveys of people who have used heroin find that the typical user starts out snorting heroin (as Lennon did), progresses to injecting heroin under the skin but not into blood vessels (termed skin popping), and then ends up injecting into blood vessels (termed mainlining). Injecting heroin causes a more intense experience—a “rush,” a feeling of immediate intensity. Most users proceed from occasional use to daily use, and their primary motivation in life becomes obtaining enough money to procure the next dose, or “fix.” Because users become tolerant to the drug, they must increase the amount they use in order to get an effect.

Heroin use disorder is associated with a variety of medical problems, such as pneumonia and liver disease. In addition, heroin users who inject the drug are at risk of contracting HIV and hepatitis as well as collapsed veins—and an overdose can be fatal (NIDA, 2007c).

Hallucinogens

Hallucinogens are substances that induce sensory or perceptual distortions—hallucinations in any of the senses. That is, users think they see, hear, taste, or feel something that is not actually present or not present in the way it is perceived. Some hallucinogens also can induce mood swings. Hallucinogens frequently taken for recreational purposes include the following:

- LSD (a synthetic hallucinogen, also called acid),

- mescaline (a psychoactive substance produced by certain kinds of cacti),

- psilocybin (a psychoactive substance present in psilocybin mushrooms, commonly referred to as “magic mushrooms”), and

- marijuana (the dried leaves and flowers of the hemp plant, cannabis sativa).

The first three of these drugs are chemically similar to the neurotransmitter serotonin. A single moderate dose of any of these drugs (or a very high dose of marijuana) is enough to induce visual hallucinations. In what follows we examine the use disorders that can arise when people take LSD or marijuana.

LSD

All of the Beatles used LSD at one point or another, but John Lennon reported that he took LSD thousands of times—which surely would constitute abusing the drug. LSD is a hallucinogen because it alters the user’s visual or auditory sensations and perceptions; it also induces shifting emotions. LSD normally has an effect within 30 to 90 minutes of being ingested, and the effects last up to 12 hours (NIDA, 2001).

The effects of LSD can be unpredictable. A “bad trip” (that is, an adverse reaction to LSD) can include intense anxiety, fear, and dread; a user may feel as if he or she is totally losing control, going crazy, or dying. People who are alone when experiencing a bad trip may get hurt or kill themselves as they respond to the hallucinations.

Two aftereffects can occur from LSD use, even after the pharmacological effects of the drug have worn off: psychosis (hallucinations and visual disturbances) and “flashbacks” (involuntary and vivid memories of sensory distortions that occurred while under the influence of the drug). Such aftereffects are rare, although LSD abuse can induce enduring psychotic symptoms in a small number of people (NIDA, 2007d).

Marijuana

The Beatles also smoked marijuana. The resin from the hemp plant’s flowering tops is made into another, more potent drug, hashish. The active ingredient of marijuana and hashish is tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). Both marijuana and hashish can be either smoked or ingested.

Marijuana’s effects are subtler than those of other hallucinogens, creating minor perceptual distortions that lead a person to experience more vivid sensations and to feel that time has slowed down (NIDA, 2005b). The user’s cognitive and motor abilities are also slowed or temporarily impaired, which produces poor driving skills (Ramaekers et al., 2006). THC ultimately activates the dopamine reward system (NIDA, 2000). Not everyone who uses marijuana develops a use disorder, but some people do develop such a disorder. If a person develops cannabis use disorder (as is it is called in DSM-5), he or she will experience withdrawal symptoms after he or she stops using marijuana; such symptoms include irritability, anxiety, depression, decreased appetite, and disturbed sleep (Allsop et al., 2012; Kouri & Pope, 2000). Studies have found that chronic marijuana use adversely affects learning, memory, and motivation—even when the user has not taken the drug recently and is not under its direct influence (Lane et al., 2005; Pope et al., 2001; Pope & Yurgelin-Todd, 1996). These effects are particularly likely to occur if the person started to use marijuana heavily during adolescence (Meier et al., 2012).

Dissociative Anesthetics

A dissociative anesthetic produces a sense of detachment from the user’s surroundings—a dissociation. The word anesthetic in the name reflects the fact that many of these drugs were originally developed as anesthetics to be used during surgery. Dissociative anesthetics act like depressants and also affect glutamate activity (Kapur & Seeman, 2002). These drugs can distort visual and auditory perception. Drugs of this type are included in the term “club drugs” because they tend to be taken before or during an evening of dancing at a nightclub. The most commonly abused members of this class of drugs are phencyclidine and ketamine, which we discuss in the following sections.

Phencyclidine (PCP)

Phencyclidine (PCP, also known as “angel dust” and “rocket fuel”) became a street drug in the 1960s. It can be snorted, ingested, or smoked, and users can quickly begin to take it compulsively. PCP abusers may report feeling powerful and invulnerable while the drug is in their system, but they may become violent or suicidal (NIDA, 2007f).

PCP has deleterious effects even when taken at low to moderate doses. Medical effects include increased blood pressure, heart rate, and sweating, coordination problems, and numbness in the hands and feet. At higher doses, PCP users may experience hallucinations, delusions, paranoia, disordered thinking, and memory problems as well as speech and cognitive problems (as did the man in Case 9.5)—even up to a year after last use (NIDA, 2007f).

CASE 9.5 • FROM THE OUTSIDE: Phencyclidine Use Disorder

The patient is a 20-year-old man who was brought to the hospital, trussed in ropes, by his four brothers. This is his seventh hospitalization in the last 2 years, each for similar behavior. One of his brothers reports that he “came home crazy,” threw a chair through a window, tore a gas heater off the wall, and ran into the street. The family called the police, who apprehended him shortly thereafter as he stood, naked, directing traffic at a busy intersection. He assaulted the arresting officers, escaped from them, and ran home screaming threats at his family. There his brothers were able to subdue him.

On admission, the patient was observed to be agitated, with his mood fluctuating between anger and fear. He had slurred speech and staggered when he walked. He remained extremely violent and disorganized for the first several days of his hospitalization, then began having longer and longer lucid intervals, still interspersed with sudden, unpredictable periods in which he displayed great suspiciousness, a fierce expression, slurred speech, and clenched fists.

After calming down, the patient denied ever having been violent or acting in an unusual way (“I’m a peaceable man”) and said he could not remember how he got to the hospital. He admitted using alcohol and marijuana socially, but denied phencyclidine (PCP) use except for once, experimentally, 3 years previously. Nevertheless, blood and urine tests were positive for phencyclidine, and his brother believes “he gets dusted every day.”

(Spitzer et al., 2002, p–122)

Ketamine

Ketamine (“Special K” or “vitamin K”) induces anesthesia and hallucinations and can be injected or snorted. Ketamine is chemically similar to PCP but is shorter acting and has less intense effects. With high doses, some users experience a sense of dissociation so severe that they feel as if they are dying (NIDA, 2001). Ketamine use and abuse are associated with temporary memory loss, impaired thinking, a loss of contact with reality, violent behavior, and breathing and heart problems that are potentially lethal (Krystal et al., 2005; White & Ryan, 1996). Regular users of ketamine may develop tolerance and cravings (Jansen & Darracot-Cankovic, 2001).

Understanding Other Abused Substances

In what follows, we first consider neurological factors for each class of substances and then turn to psychological and social factors.

Neurological Factors

Depending on the abused substance, different brain systems and neural communication processes are critical.

Opioids

Among the narcotic analgesics, researchers have focused most of their attention on heroin—in large part because it poses the greatest problem. Like other opioids, heroin slows down activity in the central nervous system. It directly affects the part of the brain involved in breathing and coughing—the brainstem—and thus historically was used to suppress persistent coughs. In addition, heroin binds to opioid receptors in the brain, which has the effect of decreasing pain, and indirectly activates the dopamine reward system (NIDA, 2000). Continued heroin use also decreases the production of endorphins, a class of neurotransmitters that act as natural painkillers. Thus, over time heroin abuse reduces the body’s natural pain-relieving ability. In fact, someone with heroin use disorder has his or her endorphin production reduced to the point that, when withdrawal symptoms arise, endorphins that would have kicked in to reduce pain are not able to do so, making the symptoms feel even worse than they otherwise would be.

Hallucinogens

THC, the active ingredient in marijuana, is chemically similar to the type of neurotransmitters known as cannabinoids, and it activates the dopamine reward system. People who began abusing marijuana at an early age have atrophy of brain areas that contain many receptors for cannabinoids (De Bellis et al., 2000; Ernst & Chefer, 2001; Wilson et al., 2000), especially the hippocampus and the cerebellum. Atrophy of the hippocampus can explain why chronic marijuana users develop memory problems, and atrophy of the cerebellum can explain why they develop balance and coordination problems. Cannabinoids also modulate other neurotransmitters and affect pain and appetite (Wilson & Nicoll, 2001).

The genetic bases of abuse of most types of substances have not been studied in depth. However, one twin study of cannabis use disorder (Lynskey et al., 2002) estimated that genes account for 45% of the variance in vulnerability to cannabis use disorder, shared environmental factors account for 20%, and nonshared environmental factors account for the remaining 35%.

Dissociative Anesthetics

PCP and ketamine increase the level of glutamate, a fast-acting excitatory neurotransmitter. Glutamate can be toxic; it actually kills neurons if too much is present. Thus, by increasing levels of glutamate, dissociative anesthetics may, eventually, lead to cell death in brain areas that have receptors for this neurotransmitter—which would explain the memory and other cognitive deficits observed in people who abuse these drugs.

Psychological Factors

Abuse of these other types of substances is affected by most of the same psychological factors that influence abuse of stimulants and depressants (see the starred items in TABLE 9.6): observational learning, operant conditioning, and classical conditioning all contribute to substance use disorders as a maladaptive coping strategy. We examine here the unique aspects of classical conditioning that are associated with heroin use disorder.

Classical conditioning can help explain how some accidental heroin “overdoses” occur (Siegel, 1988; Siegel et al., 2000). The quotation marks around the word overdoses are meant to convey that, in fact, the user often has not taken more than usual. Rather, he or she has taken a usual dose in the presence of novel stimuli (Siegel & Ramos, 2002). If a user normally takes heroin in a particular place, such as the basement of the house, he or she develops a conditioned response to being in that place: The brain triggers biological changes to get ready for the influx of heroin, activating compensatory mechanisms to dampen the effect of the about-to-be-taken drug (see Figure 9.1). This response creates a tolerance for the drug, but—and here’s the most important point—only in that situation. The stimuli in a “neutral” setting (not associated with use of the drug), such as a bedroom, have not yet become paired with taking heroin—and hence the brain does not trigger these compensatory mechanisms before the person takes the drug. If the conditioned stimulus (e.g., the basement) is not present to elicit the compensatory response, the same dose of heroin can have a greater effect—causing an “overdose.”

Social Factors

The social factors that are commonly associated with use disorders of stimulants and depressants also apply to opioids, hallucinogens, and dissociative anesthetics (see the starred items in TABLE 9.7). These include dysfunctional family interactions and a higher proportion of substance-abusing peers, which in turn affects the perceived norms of substance use and abuse (Kuntsche et al., 2009). Moreover, economic hardship and unemployment are associated with substance use disorders, perhaps because of chronic stress that arises from economic adversity as well as increased exposure to substance abuse.

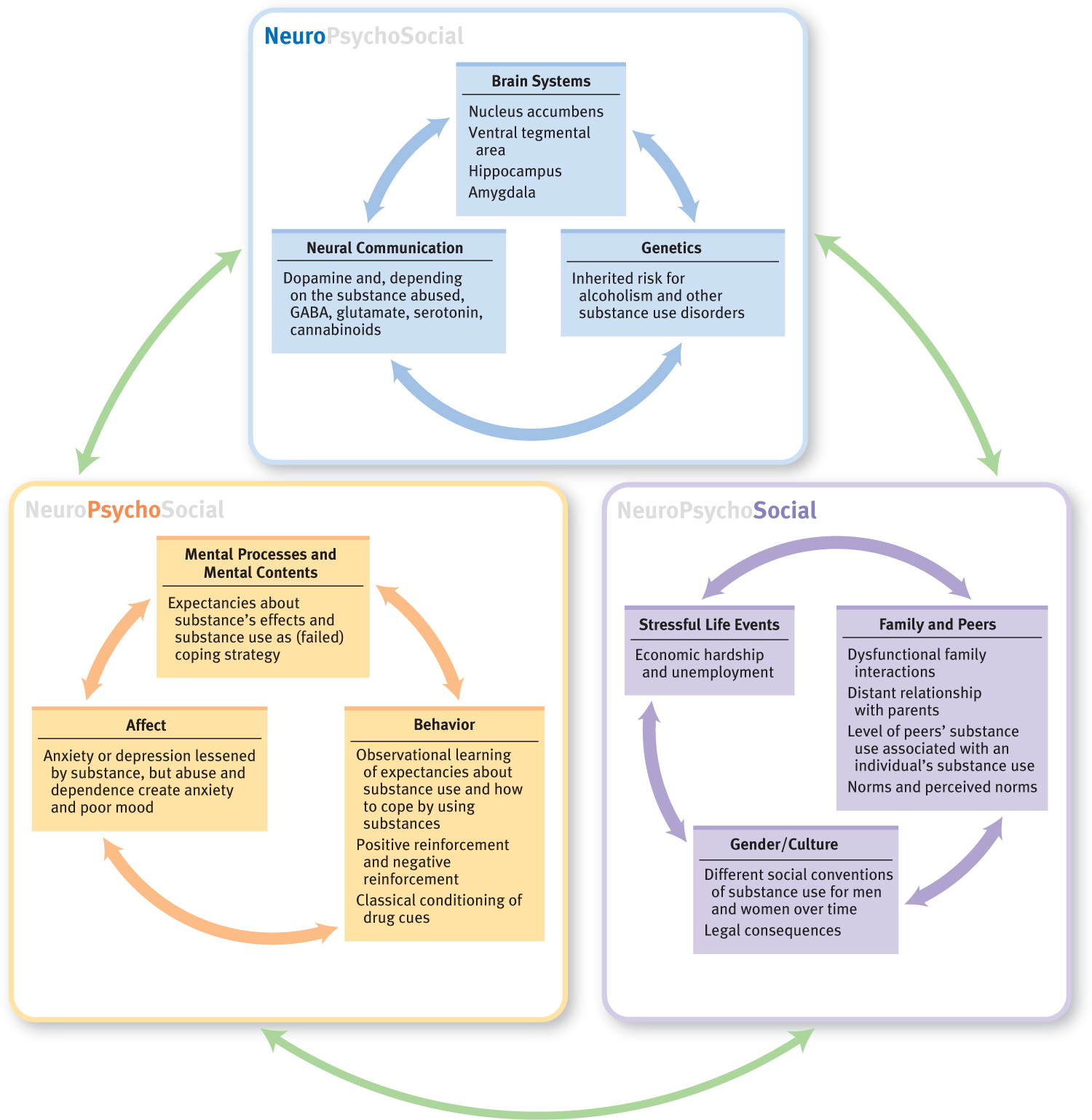

Feedback Loops in Understanding Substance Use Disorders

The neurological, psychological, and social factors that contribute to substance use disorders in general do not act in isolation but affect each other through various feedback loops (see Figure 9.8).

Clearly, neurological factors play a key role, but can do so in different ways. Some neurological factors tend to have a direct relationship with substance use disorders: The effects that a given substance produces in the brain can be directly influenced by specific genes and a person’s prior exposure to the drug—either in the mother’s womb or after birth. Neurological factors, such as genes and their influence on temperament, can also have indirect effects: For example, some people have a temperament that leads them to be more responsive to reward (and to a drug’s rewarding effects) than others are.

Psychological factors and social factors also play a role in the development of substance use disorders. Experiencing child abuse, neglect, or another significant social stressor increases the risk for substance use disorders (Compton et al., 2005). Moreover, as we saw for alcohol use, peer and family interactions and culture (social factors) help determine perceived social norms, which in turn alter a person’s expectations about the effects of taking a substance and his or her willingness to try the substance or continue to use it (psychological factor) (Kendler, Sundquist, et al., 2013). And once a person has tried a drug, its specific neurological effects and other consequences of its use—such as whether the experience of taking the drug is reinforced and how friends respond to the drug use (psychological and social factors)—will affect how likely the person is to continue using it.

Thinking Like A Clinician

Nat didn’t care much for drinking; his drugs of choice were ketamine and LSD. His friends worried about him, though, because every weekend he’d either be clubbing (and taking ketamine) or tripping on LSD. What might be some of the sensations and perceptions that each drug induced in Nat, and why might his friends be concerned about him? Suppose he stopped using LSD but started smoking marijuana daily. What symptoms might he experience, and why might his friends become concerned? If he switched from taking ketamine to snorting heroin before clubbing, what difference might it make in the long term?

How would you determine whether Nat’s substance use should be considered a use disorder? What other information might you want to know before making such a judgment? Do you think he might develop withdrawal symptoms? Why or why not? If so, which ones? According to the neuropsychosocial approach, what factors might underlie Nat’s use of drugs?