9.5 Treating Substance Use Disorders

Three of the four Beatles were known to have at least one type of substance use disorder: George Harrison, on nicotine (cigarettes), Ringo Starr on alcohol (for which he received treatment), and John Lennon on alcohol and heroin. It is not known whether any of the Beatles (other than Starr) received professional treatment for their use disorder.

We begin by considering the goals of treatment and what the best outcomes can be. Then we examine the treatments that target each of the three types of factors, and, when appropriate, note the use of specific treatments for particular types of substance use disorders. However, as we shall see, many treatments that target psychological and social factors can effectively treat more than one type of substance use disorder.

Goals of Treatment

Treatments for substance use disorders can have two competing ultimate goals. One goal is abstinence—leading the person to stop taking the substance entirely. When this is the goal of treatment, relapse rates tend to be high (up to 60%, by some estimates), particularly among patients with comorbid disorders (Brown & D’Amico, 2001; Curran et al., 2000; NIDA, 1999, 2008f). To help patients achieve abstinence, pharmaceutical companies have focused their efforts on developing two types of medications: (1) those that minimize withdrawal symptoms and (2) those that block the “high” if the substance is used, thereby leading to extinction of the conditioned responses arising from substance use disorders.

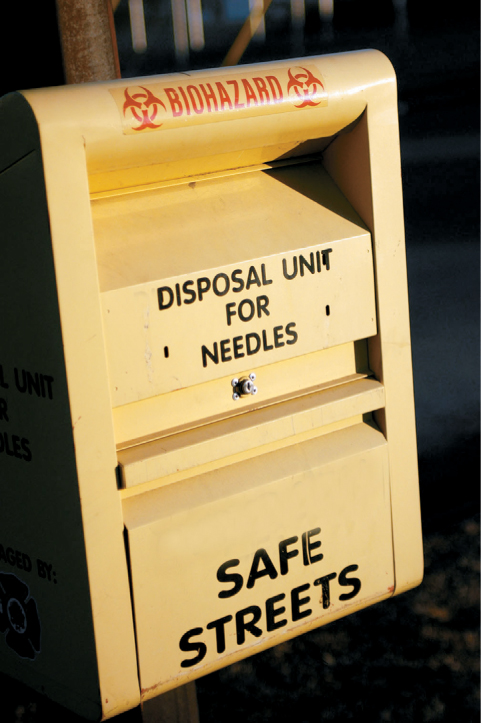

Given that abstinence-focused treatments have not been as successful as hoped, an alternative goal of treatment has emerged, which focuses on harm reduction—trying to reduce the harm to the individual and society that may come from substance use disorders. For example, needle exchange programs give users a clean needle for each heroin injection, which decreases the transmission of HIV/AIDS because users don’t need to share needles that may be contaminated. In some cases, harm reduction programs may also seek to find a middle ground between use disorders and abstinence: controlled drinking or drug use. In the United States, most treatment programs have the goal of abstinence.

CURRENT CONTROVERSY

Once an Alcoholic, Always an Alcoholic?

Most substance abuse treatment programs, especially those based on the Twelve-Step approach, insist that clients abstain from alcohol for the rest of their lives. With this approach, the assumption is that someone who has developed an alcohol use disorder will never again be able to drink without relapsing. This position is often summarized as, “Once an alcoholic, always an alcoholic.” But is this true?

Many who advocate for an abstinence-only position do so based on both personal anecdotes of problem drinkers who tried to moderate their drinking and on treatment outcome studies in which relatively small proportions of former patients were able to moderate their drinking. (Unfortunately, only small proportions manage to abstain consistently.) The abstinence-only position is also grounded in the assumption that it is safer to counsel those with a drinking problem to quit completely because it’s not possible to predict who will be able to moderate their drinking.

However, for the past 50 years, there has been growing support for the alternative position that at least some problem drinkers are able to moderate or control their drinking (Sobell & Sobell, 2006). Successful controlled drinking is typically defined as a reduction in the amount or frequency of consumption and the experience of fewer if any negative substance-related consequences associated with that consumption (e.g., Rosenberg, 2002). Research reviews suggest that problem drinkers are more likely to moderate their drinking if they have not adopted an “alcoholic identity,” have selected controlled drinking as their outcome goal, are more psychologically and socially stable, and have a supportive posttreatment environment (Rosenberg, 1993). One advantage of offering controlled drinking is that it could attract and retain in treatment those problem drinkers who are ambivalent about abstaining for the rest of their lives (Ambrogne, 2002). Furthermore, behavioral techniques such as exposure to drinking cues have helped some problem drinkers moderate their consumption (Saladin & Santa Ana, 2004). Nonetheless, most treatment services in the United States and Canada do not offer controlled drinking training, even though acceptance of controlled drinking as an outcome goal is widespread in Australia and many Western Europe countries (Davis & Rosenberg, in press).

CRITICAL THINKING Based on what you have read, if a friend or family member who had a drinking problem wanted to control or moderate their drinking, on what basis would you support or resist their outcome goal? Why?

(Harold Rosenberg, Bowling Green State University)

Targeting Neurological Factors

Many treatments of substance use disorders are directed toward neurological factors.

Detoxification

Detoxification Medically supervised discontinuation of substances for those with substance use disorders; also referred to as detox.

Detoxification (also referred to as detox) is medically supervised discontinuation of substance use. Detoxification may involve a gradual decrease in dosage over a period of time to prevent potentially lethal withdrawal symptoms, such as seizures. People with use disorders of alcohol, benzodiazepine, barbiturate, or opioids should be medically supervised when they stop taking the substance, particularly if they were using high doses. Use of other drugs, such as nicotine, cocaine, marijuana, and other hallucinogens, can be stopped abruptly without fear of medical problems, although the withdrawal symptoms may be unpleasant. John Lennon was not medically supervised when he stopped using heroin, and he described his disturbing withdrawal experience in his song “Cold Turkey”: “Thirty-six hours/Rolling in pain/Praying to someone/Free me again.” Because substance use disorders can cause permanent brain changes (which are evident even years after withdrawal symptoms have ceased; Hyman, 2005), O’Brien (2005) proposed that treatment for substance use disorders should not end with detox but rather should be a long-term venture, similar to long-term treatment for chronic diseases such as diabetes and hypertension.

Medications

Medications that treat substance use disorders operate in any of several ways: (1) They interfere with the pleasant effects of drug use; (2) they reduce the unpleasant effects of withdrawal; or (3) they help maintain abstinence. Because of the high relapse rate among those with substance use disorders, however, medications should be supplemented with the sorts of relapse prevention strategies we describe later, in the sections on treatments targeting psychological and social factors (O’Brien, 2005). We now turn to consider medications that are used to treat substance-related disorders of various specific types of drugs.

Stimulants

Of all drugs, stimulants have the most direct effects on the dopamine reward system, but medications that modify the action of dopamine receptors in this system have not yet been developed. However, some medications do affect the functioning of dopamine. For example, a medication that helps people stop smoking is bupropion (marketed as Zyban), which alters the functioning of several neurotransmitters—including dopamine. Bupropion can help to decrease cravings for methamphetamines (Killen et al., 2006; Newton et al., 2006).

Depressants

Medication for use disorders of depressants (such as alcohol use disorder) minimizes withdrawal symptoms by substituting a less harmful drug in the same category for the more harmful one. For example, longer-acting benzodiazepines, such as Valium, may be substituted for alcohol or other depressants.

Antabuse A medication for treating alcohol use disorder that induces violent nausea and vomiting when it is mixed with alcohol.

Disulfiram (Antabuse), a medication for treating alcohol use disorder, relies on a different approach. Antabuse causes violent nausea and vomiting when it is mixed with alcohol. When an alcoholic takes Antabuse and then drinks alcohol, the resulting nausea and vomiting should condition the person to have negative associations with drinking alcohol. When Antabuse is taken consistently, it leads people with alcohol use disorder to drink less frequently (Fuller et al., 1986; Sereny et al., 1986). However, many patients choose to stop taking Antabuse instead of giving up drinking alcohol (Suh et al., 2006).

Naltrexone (reVia and Vivitrol) is another medication used to treat alcohol use disorder; after detox, it can help maintain abstinence. Naltrexone indirectly reduces activity in the dopamine reward system, making drinking alcohol less rewarding; it is the most widely used medication to treat alcoholism in the United States, and it has minimal side effects.

Finally, people with alcohol use disorder who are undergoing detox may develop seizures; to prevent seizures and decrease symptoms of DTs, patients may be given benzodiazepines, along with the beta-blocker atenolol. However, a patient with DTs should be hospitalized (Arana & Rosenbaum, 2000).

Opioids

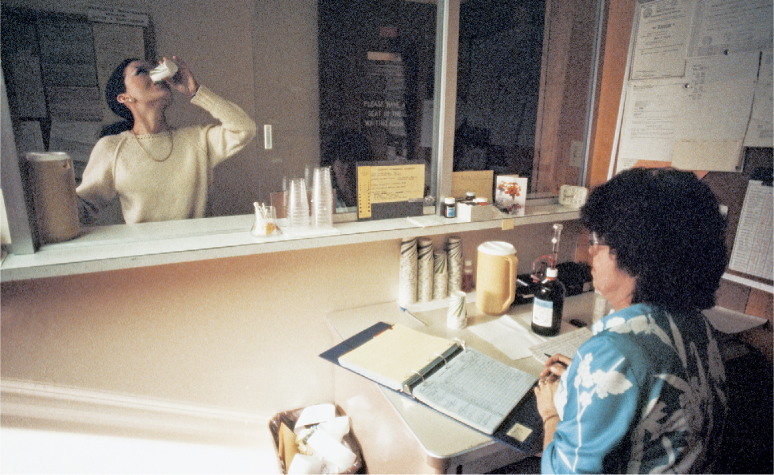

Medications that are used to treat opioid use disorder are generally chemically similar to the drugs but reduce or eliminate the “high”; treatments with these medications seek harm reduction because the medications are a safer substitute. For instance, heroin users may be given methadone, a synthetic opiate that binds to the same receptors as heroin. For about 24 hours after a current or former heroin user has taken methadone, taking heroin will not lead to a high because methadone prevents the heroin molecules from binding to the receptors. Methadone also prevents heroin withdrawal symptoms and cravings (NIDA, 2007c). Treatment of opioid use disorder with substitution medications, such as methadone, is generally more successful than promoting abstinence (D’Ippoliti et al., 1998; Strain et al., 1999; United Nations International Drug Control Programme, 1997).

Because methadone can produce a mild high and is effective for only 24 hours, patients on methadone maintenance treatment generally must go to a clinic to receive a daily oral dose, a procedure that minimizes the sale of methadone on the black market. Methadone blocks only the effects of heroin, so those taking it might still use cocaine or other drugs to experience a high (El-Bassel et al., 1993). Another medication, LAAM (levo-alpha-acetyl-methadol), blocks the effects of opioids for up to 72 hours and does not produce a high. However, LAAM can cause heart problems and so is prescribed only for patients with opioid use disorder when other treatments have proven inadequate.

Methadone and LAAM are generally available only in drug treatment clinics. However, people seeking medication to treat opioid use disorder can receive a prescription for buprenorphine (Subutex) in a doctor’s office. Buprenorphine is also available in combination with naloxone (Suboxone). In either preparation, buprenorphine has less potential for being abused than methadone because it does not produce a high.

Naltrexone is also used to treat alcohol use disorder and, in combination with buprenorphine, to treat opioid use disorder (Amass et al., 2004). Naltrexone is generally most effective for those who are highly motivated and willing to take medication that blocks the reinforcing effects of alcohol or opioids (Tomkins & Sellers, 2001).

Finally, the beta-blocker clonidine (Catapres) may help with withdrawal symptoms (Arana & Rosenbaum, 2000). A summary of medications used to treat substance use disorders is found in TABLE 9.9.

| Class of drugs | To treat withdrawal | To promote maintenance |

|---|---|---|

| Depressants | Longer-acting depressants (such as Valium) that block withdrawal symptoms | Antabuse, naltrexone |

| Narcotic analgesics | Methadone, buprenorphine, clonidine | Methadone, buprenorphine, LAAM, naltrexone |

Hallucinogens

People who abuse LSD and want to quit can generally do so without withdrawal symptoms or significant cravings. Thus, marijuana is the only substance in this category that has been the focus of research on treatment, which generally targets psychological factors and social factors, not neurological ones (McRae et al., 2003).

Targeting Psychological Factors

Treatments that target psychological factors focus on four elements: (1) increasing a user’s motivation to cease or decrease substance use, (2) changing the user’s expectations of the drug experience, (3) increasing the user’s involvement in treatment, and (4) decreasing the (classically and operantly) conditioned behaviors associated with use of the drug. We first consider motivation, and then see how CBT and Twelve-Step Facilitation address other aspects of treatment.

Motivation

For people with substance use disorders, stopping or decreasing use is at best unpleasant and at worst is very painful and extremely aversive. Therefore, the user’s motivation to stop or decrease strongly affects the ultimate success of any treatment.

Stages of Change

Extensive research has led to a theory of treatment that posits different stages of readiness for changing problematic behaviors. Research on this theory of stages of change has also led to methods that promote readiness for the next stage (Prochaska et al., 2007). Whereas most other treatments rely on a dichotomous view of substance use—users are either abstinent or not—this approach rests on the idea of intermediate states between these two extremes; the five stages of readiness to change are as follows:

- Precontemplation. The user does not admit that there is a problem and doesn’t intend to change. A temporary decrease in use in response to pressure from others will be followed by a relapse when the pressure is lifted.

- Contemplation. The user admits that there is a problem and may contemplate taking action. However, no actual behavioral change occurs at this stage; behavior change is considered for the future.

- Preparation. The user is prepared to change. He or she has a specific commitment to change, a plan for change, and the ability to adjust the plan of action and intends to start changing the substance use within a month. The user is very aware of the abuse, how it reached its current level, and available solutions. Although users in this stage are prepared to change, some are more ambivalent than others and may revert to the contemplation stage.

- Action. The user actually changes his or her substance use behavior and environment. At this stage, others most clearly perceive the user’s intentions to stop or decrease substance use; it is during this stage that family members and friends generally offer the most help and support.

- Maintenance. The user builds on gains already made in stopping or decreasing substance use and tries to prevent relapses. Former substance users who do not devote significant amounts of energy and attention to relapse prevention are likely to relapse all the way back to the contemplation—or even the precontemplation—stage. Friends and family members often mistakenly think that because the substance abuse has stopped or diminished, the former user is finished taking action. In fact, the former user must actively prevent relapses, and help and support from friends and family members is very important in this stage.

Stages of change A series of five stages that characterizes how ready a person is to change problematic behaviors: precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance.

This description of the five steps suggests a lock-step process: Each stage has discrete tasks that lead to the next stage in a linear progression. Research, however, suggests that the stages are not mutually exclusive (Littell & Girvin, 2002). For example, most people in the stage of action have occasional relapses and engage in the unwanted behavior, but they do not totally relapse into the old patterns. Also, uninterrupted forward progress is not the most typical path. People often regress before moving forward again. For example, only 5% of smokers who think about quitting go through all the stages of change within 2 years without a relapse (Prochaska, Velicer, et al., 1994).

Motivational Enhancement Therapy

Motivational enhancement therapy A form of treatment specifically designed to boost a patient’s motivation to decrease or stop substance use by highlighting discrepancies between stated personal goals related to substance use and current behavior; also referred to as motivational interviewing.

Motivational enhancement therapy (also referred to as motivational interviewing) is specifically designed to boost patients’ motivation to decrease or stop substance use (Bagøien et al., 2013; Hettema et al., 2005; Miller & Rollnick 1992). In this therapy, the patient sets his or her own goals regarding substance use, and the therapist points out discrepancies between the user’s stated personal goals and his or her current behavior. The therapist then draws on the user’s desire to meet the goals, helping him or her to override the rewarding effects of drug use. Therapists using motivational enhancement therapy do not dispense advice or seek to increase any specific skills; rather, they focus on increasing the motivation to change drug use, discussing both positive and negative aspects of drug use, reasons to quit, and how change might begin (Miller, 2001).

Studies have shown that this treatment is more successful when patients have a positive relationship with their therapist and are at the outset strongly motivated to obtain treatment (Etheridge et al., 1999; Joe et al., 1999). The beneficial effects of motivational enhancement therapy tend to fade over the course of a year (Hettema et al., 2005).

Cognitive-Behavior Therapy

Cognitive-behavior therapy (CBT) for substance use disorders has three general foci:

- understanding and changing thoughts, feelings, and behaviors that lead to substance use;

- understanding and changing the consequences of the substance use; and

- developing alternative behaviors to substitute for substance use (Carroll, 1998; Marlatt & Gordon, 1985).

CBT treatment may focus in particular on decreasing the positive consequences of drug use and on increasing the positive consequences of abstaining from drug use (referred to as abstinence reinforcement). As patients are able to change these consequences, they should be less motivated to abuse the substance. CBT may be used more generally for contingency management, in which reinforcement is contingent on the desired behavior’s occurring, or the undesired behavior’s not occurring (Stitzer & Petry, 2006).

CBT has been used to treat a variety of types of substances, including heroin and cocaine (Higgins et al., 1993; Higgins & Silverman, 1999; Petry et al., 2011). The desired behavior (such as attendance at treatment sessions or abstinence from using cocaine, as assessed by urine tests) is reinforced with one or more of these consequences:

- monetary vouchers, the value of which increases with continued abstinence (Jones et al., 2004; Silverman et al., 1999, 2001, 2004);

- decreasing the frequency of mandatory counseling sessions if treatment has been court ordered;

- more convenient appointment times; or

- being allowed to take home a small supply of methadone (requiring fewer trips to the clinic) for people being treated for heroin use disorder.

Positive incentives (obtaining reinforcement for a desired behavior) are more effective than negative consequences (i.e., punishment, such as taking away privileges) in helping patients to stay in treatment and to decrease substance use (Carroll & Onken, 2005). The cost of providing such rewards can be high, and relapse often increases once rewards are discontinued, which limits the practicality and effectiveness of abstinence reinforcement as a long-term treatment (Carroll & Onken, 2005).

Once the patient has stopped abusing the substance, CBT may focus on preventing relapse by extinguishing the conditioned response (including cravings) to drug-related cues. Treatment may also focus on decreasing the frequency or intensity of emotional distress, which can contribute to relapse (Vuchinich & Tucker, 1996). One way treatment can help patients regulate emotional distress is by helping them to develop healthier coping skills, which will then increase self-control. Thus, many of the CBT methods used to treat depression and anxiety also can be effective here; such methods include self-monitoring, cognitive restructuring, problem solving, and various relaxation techniques.

Twelve-Step Facilitation (TSF)

Twelve-Step Facilitation (TSF) is based on the 12 steps or principles that form the basis of Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) (see TABLE 9.10). AA views alcohol abuse as a disease that can never be cured, although alcohol-related behaviors can be modified by the alcoholic’s recognizing that he or she has lost control and is powerless over alcohol, turning to a higher power for help, and seeking abstinence. Research suggests that the AA approach can help people who are trying to stop their substance abuse (Laffaye et al., 2008).

|

|

Source: www.aa.org/en_pdfs/smf-121_en.pdf. The Twelve Steps are reprinted with permission of Alcoholics Anonymous World Services, Inc. (“AAWS”) Permission to reprint the Twelve Steps does not mean that AAWS has reviewed or approved the contents of this publication, or that AAWS necessarily agrees with the views expressed herein. A.A. is a program of recovery from alcoholism only- use of the Twelve Steps in connection with programs and activities which are patterned after A.A., but which address other problems, or in any other non-A.A. context, does not imply otherwise. |

AA’s groups are leaderless, whereas TSF’s groups are led by mental health professionals, whose goal is to help group members become ready to follow the 12 steps of AA. The Twelve-Step model has been used by people who abuse narcotics (Narcotics Anonymous [NA]) and in numerous inpatient and outpatient treatment programs run by mental health professionals (Ries et al., 2008). TSF targets motivation to adhere to the steps. In essence, its goals are like those of motivational enhancement therapy, but the enhanced motivation focuses on sticking with a specific type of treatment.

Targeting Social Factors

Treatments that target social factors aim to change interpersonal and community antecedents (i.e., the events that lead up to) and consequences of substance abstinence and use. Antecedents might be addressed by decreasing family tensions, increasing summer employment among teens, and decreasing community violence. Consequences might be addressed by increasing community support for abstinence and providing improved housing or employment opportunities for reduced use or for abstinence.

Residential Treatment

Some people who seek treatment for substance use disorders may need more intensive help, such as the assistance that can be found in residential treatment (also called inpatient treatment or psychiatric hospitalization), which provides a round-the-clock therapeutic environment (such as the Betty Ford Center in California). Because it is so intensive, residential treatment can help a person more rapidly change how he or she thinks, feels, and behaves. Some residential treatment programs have a spiritual component. Depending on the philosophy of the program, various combinations of methods—targeting neurological, psychological, and social factors—may be available.

Group-Based Treatment

Treatments that target social factors are usually provided in groups. One approach focuses on providing group therapy, which typically takes place in residential treatment programs, methadone clinics, drug counseling centers, and day-treatment programs (to which patients come during the day to attend groups and receive individual therapy but do not stay overnight—also called partial hospitalization or intensive outpatient treatment). In addition, there are a number of self-help groups for people with substance use disorders.

Group Therapy

CBT may be used in a group format to help people with substance use disorders. The group provides peer pressure and support for abstinence (Crits-Christoph et al., 1999). Moreover, members may use role-playing to try out new skills, such as saying “no” to friends who offer drugs. Other types of groups include social-skills training groups, where members learn ways to communicate their feelings and desires more effectively, and general support groups to decrease shame and isolation as members change their substance abuse patterns.

Self-Help Groups

Self-help groups (sometimes called support groups), such as those that adopt the Twelve-Step programs of Alcoholics Anonymous and Narcotics Anonymous, hold regular meetings. Attending such a group might supplement other treatment or might be the only treatment a person pursues. As noted earlier, such groups often view belief in a “higher power” as crucial to recovery, and even people who are not religious can improve through such meetings (Humphreys & Moos, 2007; Moos & Timko, 2008). AA also provides social support, both from other group members and from a sponsor—a person with years of sobriety who serves as a mentor and can be called up when the newer member experiences cravings or temptations to drink again. A variety of other self-help groups and organizations address recovery from substance use disorders without a Twelve-Step religious or spiritual component.

A meta-analysis showed that attending a self-help group at least once a week is associated with drug or alcohol abstinence (Fiorentine, 1999). Other research confirms that longer participation in AA is associated with better outcomes (Moos & Moos, 2004). Just like group therapy, a self-help group can be invaluable in decreasing feelings of isolation and shame. In general, self-help groups can be valuable sources of information and support, not only for the person with a substance use disorder but also for his or her relatives.

Family Therapy

Family therapy A treatment that involves an entire family or some portion of a family.

Family therapy is a treatment that involves an entire family or some portion of a family. Family therapy can be performed using any theoretical approach; the main focus is on the family rather than the individual. The goals of this type of therapy are tailored to the specific problems and needs of each family, but such therapy typically addresses issues related to communication, power, and control (Hogue et al., 2006). To the extent that family interactions lead to or help sustain abuse of a substance, changing the patterns of interaction in a family can modify these factors (Saatcioglu et al., 2006; Stanton & Shadish, 1997). Among adolescents treated for substance use disorders, outpatient family therapy can help them to abstain (Smith et al., 2006; Szapocznik et al., 2003), which suggests that changes in how parents and adolescents interact can promote and maintain abstinence. In fact, family therapy is usually a standard component of treatment for adolescents with substance use disorders (Austin et al., 2005).

Feedback Loops in Treating Substance Use Disorders

The following considerations help determine whether an intervention was successful. Did the person:

- complete the treatment, or is he or she still using or abusing the substance? (Is he or she abstinent—yes or no?)

- experience fewer harmful effects from the substance? (Is he or she using clean needles or no longer drinking to the point of passing out?)

- decrease use of the substance? (How much is the person using after treatment?)

- come to behave more responsibly? (Does he or she attend regular AA meetings or get to work on time?)

- feel better? (Is the person less depressed, anxious, “strung out,” or are drug cravings less intense?)

- come to conform to societal norms? (Has he or she stayed out of jail?)

The treatments we’ve discussed can lead to improvement according to these considerations, but different types of treatments provide different paths toward improvement. Moreover, many people with substance use disorders may quit multiple times. In addition, like studies of treatments for other types of disorders, studies of treatments for substance use disorders have found a dose-response relationship: Longer treatment produces better outcomes than shorter treatment (Hubbard et al., 1989; Simpson et al., 2002). And for those people who abuse more than one type of substance, treatment is most effective when it addresses the entire set of substances.

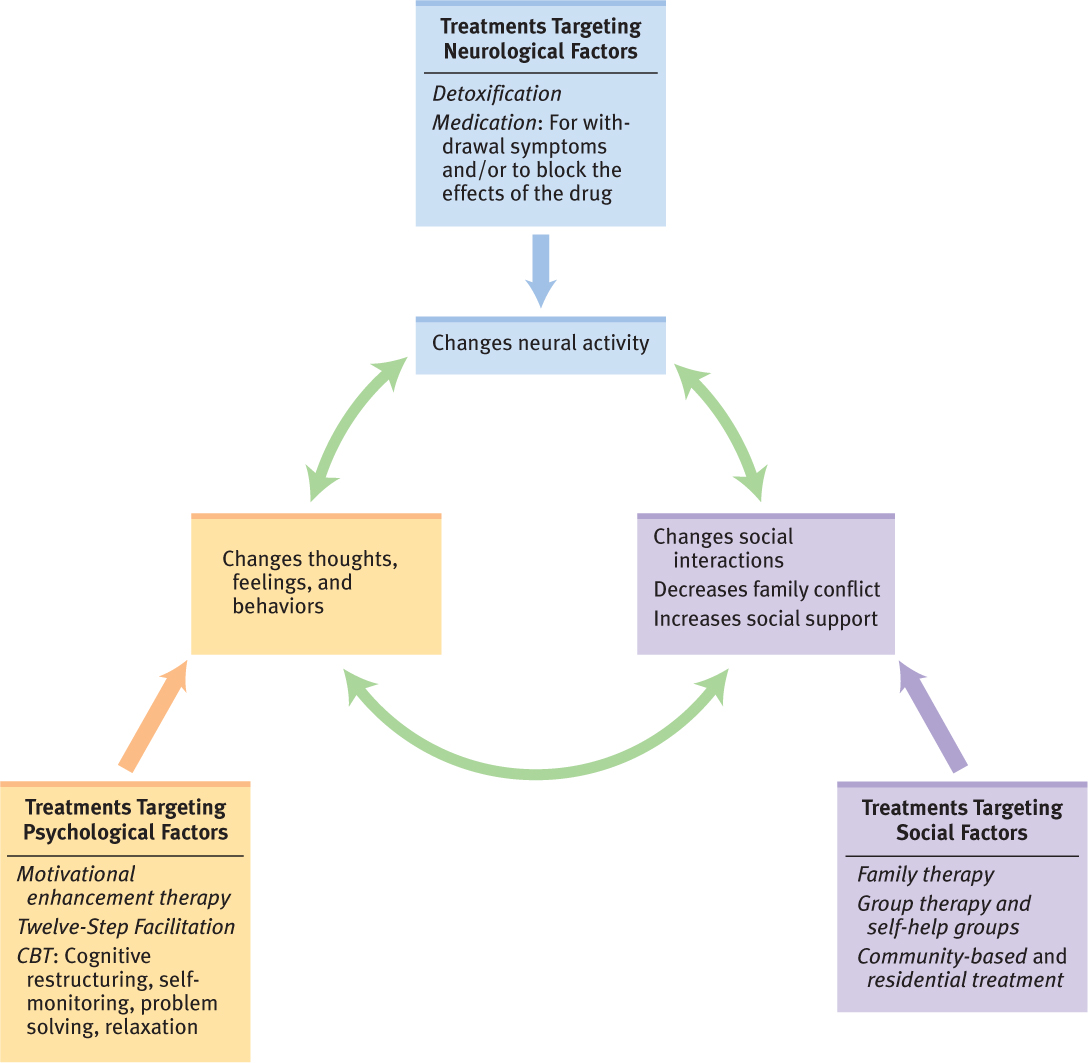

Ultimately, all successful treatments address all three types of factors that are identified in the neuropsychosocial approach. When people with a substance use disorder first stop abusing the substance, they will experience changes that are, at minimum, uncomfortable (neurological and psychological factors). Moreover, how they think and feel about themselves will change (psychological factor)—from “abuser” or “addict” to “ex-abuser” or “in recovery.” Their interactions with others will change (social factors): Perhaps they will make new friends who don’t use drugs, avoid friends who abuse drugs, behave differently with family members (who in turn may behave differently toward them), perform better at work, or have fewer run-ins with the law. Other people’s responses to them will also affect their motivation to continue to avoid using the substance and endure the uncomfortable withdrawal effects and ignore their cravings. Thus, as usual, treatment ultimately relies on feedback loops among the three types of factors (see Figure 9.9).

Thinking Like A Clinician

Karl has been binge drinking and smoking marijuana every weekend for the past couple years. He’s been able to maintain his job, but Monday mornings he’s in rough shape, sometimes he’s had blackouts when he drinks. He’s decided that he wants to quit drinking and smoking marijuana, but he feels that he needs some help to do so. Based on what you’ve read in this chapter, what would you advise for Karl, and why? What wouldn’t you suggest him as an appropriate treatment, and why? How would your answer change if he’d been cocaine frequently?