10.1 Anorexia Nervosa

After years of struggling with bulimia, Marya Hornbacher began “inching” toward anorexia; she gradually became significantly underweight by severely restricting her food intake, refusing to eat enough to obtain a healthy weight:

Anorexia started slowly. It took time to work myself into the frenzy that the disease demands. There were an incredible number of painfully thin girls at [school], dancers mostly. The obsession with weight seemed nearly universal. Whispers and longing stares followed the ones who were visibly anorexic. We sat at our cafeteria tables, passionately discussing the calories of lettuce, celery, a dinner roll, rice.

(Hornbacher, 1998, p. 102)

Hornbacher wanted to be thin, to be in control of her eating, and to feel more in control of herself generally. She began to eat less and less, to the point where she began to pass out at school.

What Is Anorexia Nervosa?

Key features of anorexia nervosa (often referred to simply as anorexia) are that the person will not maintain at least a low normal weight and employs various methods to prevent weight gain (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Despite medical and psychological consequences of a low weight, people who have anorexia nervosa continue to pursue extreme thinness. Anorexia has a high risk of death: About 10–15% of people hospitalized with anorexia eventually die as a direct or indirect consequence of the disorder (Zipfel et al., 2000).

Anorexia Nervosa According to DSM-5

To be diagnosed with anorexia nervosa according to DSM-5, symptoms must meet three criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 2013):

- A significantly low body weight for the person’s age and sex, which results from not ingesting enough calories relative to the calories burned. Being slightly underweight is not enough.

- An intense fear of becoming fat or gaining weight, or behaving in ways that interfere with weight gain, despite being significantly underweight. This fear is often the primary reason that the person refuses to attain a healthy weight. A person who has anorexia is obsessed with her body and food, and her thoughts and beliefs about these topics are usually illogical or irrational, such as imagining that wearing a certain clothing size is “worse than death.” Moreover, her feelings about herself rise and fall with her caloric intake, weight, or how her clothes seem to fit. If someone with anorexia eats 50 more calories (for comparison, a single pat of butter provides about 35 calories) than she had allotted for her daily intake, she may experience intense feelings of worthlessness. People who suffer from anorexia often deny that they have a problem and do not see their low weight as a source of concern.

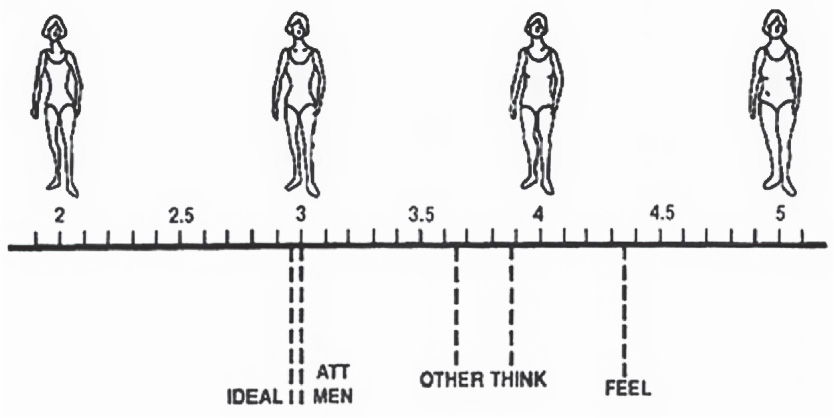

- Distortions of body image (the person’s view of her body). People with anorexia often feel that their bodies are bigger and “fatter” than they actually are and overly value their body’s weight or shape (see Figure 10.1). Note that people who have anorexia and people who have body dysmorphic disorder both have a distorted body image (Chapter 7); however, people with anorexia focus on overall body shape and weight, whereas people with body dysmorphic disorder typically focus on the face or a single body part. Moreover, the former typically have an actual physical problem with their body (that is—they are in fact significantly underweight) that they typically do not want to improve, whereas the latter have no or only a minimal “defect” but perceive it to be significant and want to hide it or minimize it in other ways (Hrabosky et al., 2009).

FIGURE 10.1 • Body Image Distortion With respect to body image, women with anorexia may simply represent an extreme end of “normal” distortions; many other women do not assess their bodies accurately (Thompson, 1990). Here IDEAL is the average figure that women rated as ideal. ATT MEN (“attractive to men”) shows the average figure that women rated as most attractive to men, whereas OTHER illustrates the average figure that men selected as most attractive. THINK depicts the average figure that women thought of as best matching their own, and FEEL depicts the average figure that women felt best matches their own.Source: Larry Pasman, J. Kevin Thompson, International Journal of Eating Disorders Copyright © 1988 Wiley Periodicals, Inc., A Wiley Company.

FIGURE 10.1 • Body Image Distortion With respect to body image, women with anorexia may simply represent an extreme end of “normal” distortions; many other women do not assess their bodies accurately (Thompson, 1990). Here IDEAL is the average figure that women rated as ideal. ATT MEN (“attractive to men”) shows the average figure that women rated as most attractive to men, whereas OTHER illustrates the average figure that men selected as most attractive. THINK depicts the average figure that women thought of as best matching their own, and FEEL depicts the average figure that women felt best matches their own.Source: Larry Pasman, J. Kevin Thompson, International Journal of Eating Disorders Copyright © 1988 Wiley Periodicals, Inc., A Wiley Company.

Research suggests that people with anorexia also have distorted perceptions of the size of their meal portions, overestimating how much food is in a portion (Milos et al., 2013). TABLE 10.1 lists the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for anorexia; additional facts about anorexia are provided in TABLE 10.2, and Caroline Knapp, Case 10.1, provides a glimpse of life with anorexia.

|

| Reprinted with permission from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, (Copyright ©2013). American Psychiatric Association. All Rights Reserved. |

Prevalence

|

Comorbidity

|

Onset

|

Course

|

Gender Differences

|

Cultural Differences

|

CASE 10.1 • FROM THE INSIDE: Anorexia Nervosa

Caroline Knapp suffered from both anorexia and alcohol use disorder (see the excerpt from her book, Drinking: A Love Story, in Chapter 9, Case 9.3). In describing her relationship with food, she noted that people with anorexia nervosa develop bizarre eating habits and a kind of tunnel vision—focusing on food, on eating, and on not eating:

When you’re starving…it’s hard to think about anything else [except eating or not eating. It’s] very hard to see the larger picture of options that is your life, very hard to consider what else you might need or want or fear were you not so intently focused on one crushing passion. I sat in my room every night, with rare exceptions, for three-and-a-half years. In secret, and with painstaking deliberation, I carved an apple and one-inch square of cheddar cheese into tiny bits, sixteen individual slivers, each one so translucently thin you could see the light shine through it if you held it up to a lamp. Then I lined up the apple slices on a tiny china saucer and placed a square of cheese on each. And then I ate them one by one, nibbled at them like a rabbit, edge by tiny edge, so slowly and with such concentrated precision the meal took two hours to consume. I planned for this ritual all day, yearned for it, carried it out with the utmost focus and care.

(Knapp, 2003, pp. 48–49)

If, as you read Knapp’s description of her eating ritual, you were reminded of symptoms of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD, see Chapter 7), you’re on to something. Some symptoms of anorexia overlap with symptoms of OCD and related disorders: obsessions about symmetry, compulsions to order objects precisely, and hoarding. However, other symptoms of OCD—such as obsessions about contamination and checking and cleaning compulsions—do not overlap with those of anorexia (Halmi et al., 2003).

Two Types of Anorexia Nervosa: Restricting and Binge Eating/Purging

Binge eating Eating much more food at one time than most people would eat in the same period of time or context.

Purging Attempting to reduce calories that have already been consumed by vomiting or using diuretics, laxatives, or enemas.

People with anorexia become extremely thin and maintain their very low weight by using one of two methods: restricting what they eat or binge eating and then purging. DSM-5 categorizes two types of anorexia, based on which method is used:

- Restricting type. Low weight is achieved and maintained through severe undereating or excessive exercise. (Mental health clinicians consider exercise to be excessive if the person feels high levels of guilt when she postpones or misses a workout; Mond et al., 2006.) There is no binge eating or purging. This is the classic type of anorexia, and Knapp’s description in Case 10.1 illustrates the pattern of eating that is common among people with the restricting type.

- Binge eating/purging type. Some people with anorexia may engage in binge eating—eating much more food at one time than most people would eat in the same period of time or context. People often feel out of control while binge eating. For example, a “snack” might consist of a pint or two of ice cream with a whole jar of hot fudge sauce, and the person feels unable to stop at just one scoop. Among people with anorexia, binge eating is followed by purging, which is an attempt to reduce the ingested calories by vomiting or by using diuretics, laxatives, or enemas.

Medical, Psychological, and Social Effects of Anorexia Nervosa

Anorexia has serious negative effects on many aspects of bodily functioning. Because of the daily deficit between calories needed for normal functioning and calories taken in, the body tries to make do with less. However, this process comes at a high cost.

Medical Effects of Anorexia

One possible effect of anorexia is that the heart muscle becomes thinner as the body, using available energy sources to meet its caloric demands, cannibalizes muscle generally and the heart muscle in particular. Muscle wasting is the term used when the body breaks down muscle in order to obtain needed calories. When people with anorexia exercise, they are not building muscle but losing it, especially heart muscle—which can be fatal. Excessive exercise is actively discouraged in people with anorexia, and even modest exercise may be discouraged, depending on the person’s weight and medical status.

A physical examination and lab tests are likely to reveal other medical effects of anorexia, as the body adjusts to conserve energy. These include low heart rate and blood pressure, abdominal bloating or discomfort, constipation, loss of bone density (leading to osteoporosis and easily fractured bones), and a slower metabolism (which leads to lower body temperature, difficulty tolerating cold temperatures, and downy hairs forming on the body to provide insulation) (Mascolo et al., 2012). More visible effects include dry and yellow-orange skin, brittle nails, and loss of hair on the scalp. Symptoms that may not be as obvious to others include irritability, fatigue, and headaches (Mehler, 2003; Pomeroy, 2004). People with anorexia may also appear hyperactive or restless, which is probably a by-product of starvation, given that such behavior also occurs in starved animals (Klein & Walsh, 2005).

People with anorexia who purge may believe that they are getting rid of all the calories they’ve eaten, but they’re wrong. In a starved state, the body so desperately needs calories that once food is in the mouth, the digestive process begins more rapidly than normal, and calories may begin to be absorbed before the food reaches the stomach; even if vomiting occurs, some calories are still absorbed, although water the body needs is lost. Diuretics (i.e., substances that force the body to excrete water) decrease only water in the body, not body fat or muscle, and laxatives and enemas simply get rid of water and the body’s waste before it would otherwise be eliminated.

All four methods of purging—vomiting, diuretics, laxatives, and enemas—can result in dehydration because they all deprive the body of needed fluids. In turn, dehydration can create an imbalance in the body’s electrolytes—salts that are critical for neural transmission and muscle contractions, including those of the heart muscle. When dehydration remains untreated, it can lead to death. In addition, recent studies of the long-term consequences of starvation during puberty indicate an increased risk of heart disease (Sparén et al., 2004).

Psychological and Social Effects of Starvation

Researchers in the 1940s documented a number of unexpected psychological and social effects of extreme caloric restriction, which were first discovered in what is sometimes called the starvation study (Keys et al., 1950). When healthy young men were given half their usual caloric intake for 6 months, they lost 25% of their original weight and suffered other changes: They became more sensitive to the sensations of light, cold, and noise; they slept less; they lost their sex drive; and their mood worsened. The men lost their sense of humor, argued with one another, and showed symptoms of depression and anxiety. They also became obsessed with food—talking and dreaming about food and collecting and sharing recipes. They began to hoard food and random items such as old books and knick-knacks. These striking effects persisted for months after the men returned to their normal diets, and abnormal eating and ruminations about food continued even 50 years later (Crow & Eckert, 2000). Such findings have since been substantiated by other researchers (Favaro et al., 2000; Polivy, 1996). It is sobering that, even on this diet, the participants in the starvation study still ate more each day than do many people with anorexia.

The participants in the starvation study were psychologically healthy adult men, and they developed the noticeable symptoms after less than 6 months on what would now be considered a relatively strict diet. Most people (females) with anorexia develop the disorder when they are younger than were the men in the study and maintain unhealthy eating patterns for a longer time than the 6 months of the study; the consequences of restricting eating at a young age may be more severe than those noted in the starvation study.

Moreover, some people with anorexia may have such distorted thinking about their weight and body that they may come to believe that there’s really nothing wrong with their weight or restricted food intake (Csipke & Horne, 2007; Gavin et al., 2008). A minority may come to view anorexia as a lifestyle choice rather than a disorder. Unfortunately, anorexia has serious physical and mental health consequences, which are swept under the rug by such positive views of the condition.

Thinking Like A Clinician

Since the age of 12, Chris has been very thin, in part because of hours of soccer practice weekly. Now, at the age of 17, Chris eats very little (particularly staying away from foods high in fat), continues exercising, and gets angry when people comment about weight. What would you need to know to determine whether Chris has anorexia nervosa? If Chris does have anorexia, what would be some possible medical problems that might arise? What if Chris were male—would it change what you’d need to know to make the diagnosis? Explain your answer.