12.1 What Are Schizophrenia and Other Psychotic Disorders?

Schizophrenia A psychological disorder characterized by psychotic symptoms that significantly affect emotions, behavior, and mental processes and mental contents.

Schizophrenia is a psychological disorder characterized by psychotic symptoms—hallucinations and delusions—that significantly affect emotions, behavior, and, most notably, mental processes and mental contents. The symptoms of schizophrenia can interfere with a person’s abilities to comprehend and respond to the world in a normal way. DSM-5 lists schizophrenia as a single disorder (see TABLE 12.1), but in its chapter titled Schizophrenia Spectrum and Psychotic Disorders, it describes a group of disorders related to and including schizophrenia; research suggests that schizophrenia itself is not a unitary disorder (Blanchard et al., 2005; Turetsky et al., 2002). Instead, schizophrenia is a set of related disorders. Research findings suggest that each variant of schizophrenia has different symptoms, causes, course of development, and, possibly, response to treatments. In the following sections we examine in more detail the symptoms of schizophrenia and other related psychotic disorders.

|

| Reprinted with permission from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, (Copyright ©2013). American Psychiatric Association. All Rights Reserved. |

The Symptoms of Schizophrenia

The criteria for schizophrenia in DSM-5 fall into two clusters:

- positive symptoms, which consist of delusions and hallucinations and disorganized speech and behavior; and

- negative symptoms, which consist of the absence or reduction of normal mental processes, mental contents, feelings, or behaviors, including speech, emotional expressiveness, and/or movement.

TABLE 12.1 lists the DSM-5 criteria for schizophrenia. After considering these criteria, we discuss criticisms of these criteria and an alternative way to diagnose schizophrenia.

Positive Symptoms

Positive symptoms Symptoms of schizophrenia that are characterized by the presence of abnormal or distorted mental processes, mental contents, or behaviors.

Positive symptoms are so named because they are marked by the presence of abnormal or distorted mental processes, mental contents, or behaviors. Positive symptoms of schizophrenia are

- hallucinations (distortions of perception),

- delusions (distortions of thought),

- disorganized speech, and

- disorganized behavior.

These symptoms are extreme. From time to time, we all have hallucinations, such as thinking we hear the doorbell ring when it didn’t. But the hallucinations experienced by people with schizophrenia are intrusive—they may be voices that talk constantly or scream at the patient. Similarly, the delusions of someone with schizophrenia aren’t isolated, one-time false beliefs (e.g., “My roommate took my sweater, and that’s why it’s missing”). With schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders, the delusions are extensive, although they often focus on one topic (e.g., “My roommate is out to get me, and the fact that she has taken my sweater is just one more example”).

The positive symptoms of disorganized speech and disorganized behavior are apparent from watching or talking to a person who has them; it’s difficult, if not impossible, to understand what’s being said, and the person’s behavior is clearly odd (wearing a coat during a heat wave, for example). We next examine the four positive symptoms in more detail.

Hallucinations

Hallucinations Sensations that are so vivid that the perceived objects or events seem real, although they are not. Hallucinations can occur in any of the five senses.

As discussed in Chapter 1, hallucinations are sensations so vivid that the perceived objects or events seem real even though they are not. Any of the five senses can be involved in a hallucination, although auditory hallucinations—specifically, hearing voices—are the most common type experienced by people with schizophrenia. Pamela Spiro Wagner describes one of her experiences with auditory hallucinations:

[The voices] have returned with a vengeance, bringing hell to my nights and days. With scathing criticism and a constant scornful commentary on everything I do, they sometimes order me to do things I shouldn’t. So far, I’ve stopped myself, but I might not always be able to….

(Wagner & Spiro, 2005, p. 2)

Research that investigates possible underlying causes of auditory hallucinations finds that people with schizophrenia, and to a lesser extent their unaffected siblings, have difficulty distinguishing between verbal information that is internally generated (as when imagining a conversation or talking to oneself) and verbal information that is externally generated (as when another person is actually talking) (Brunelin et al., 2007). People with schizophrenia are also more likely to (mis)attribute their own internal conversations to another person (Brunelin, Combris, et al., 2006); this misattribution apparently contributes to the experience of auditory hallucinations.

Delusions

Delusions Persistent false beliefs that are held despite evidence that the beliefs are incorrect or exaggerate reality.

People with schizophrenia may also experience delusions—incorrect beliefs that persist, despite evidence to the contrary. Delusions often focus on a particular theme, and several types of themes are common among these patients. Persecutory delusions involve the theme of being persecuted by others. Pamela Spiro Wagner’s persecutory delusions involved extraterrestrials:

I barricade the door each night for fear of beings from the higher dimensions coming to spirit me away, useless as any physical barrier would be against them. I don’t mention the NSA, DIA, or Interpol surveillance I’ve detected in my walls or how intercepted conversations among these agencies have intruded into TV shows.

(Wagner & Spiro, 2005, p. 2)

In contrast, delusions of control revolve around the belief that the person is being controlled by other people (or aliens), who literally put thoughts into his or her head, called thought insertion:

I came to believe that a local pharmacist was tormenting me by inserting his thoughts into my head, stealing mine, and inducing me to buy things I had no use for. The only way I could escape the influence of his deadly radiation was to walk a circuit a mile in diameter around his drugstore, and then I felt terrified and in terrible danger.

(Wagner, 1996, p. 400)

Another delusional theme is believing oneself to be significantly more powerful, knowledgeable, or capable than is actually the case, referred to as grandiose delusions. Someone with this type of delusion may believe that he or she has invented a new type of computer when such an achievement by that person is clearly impossible. Grandiose delusions may also include the mistaken belief that the person is a different—often famous and powerful—person, such as the president or a prominent religious figure.

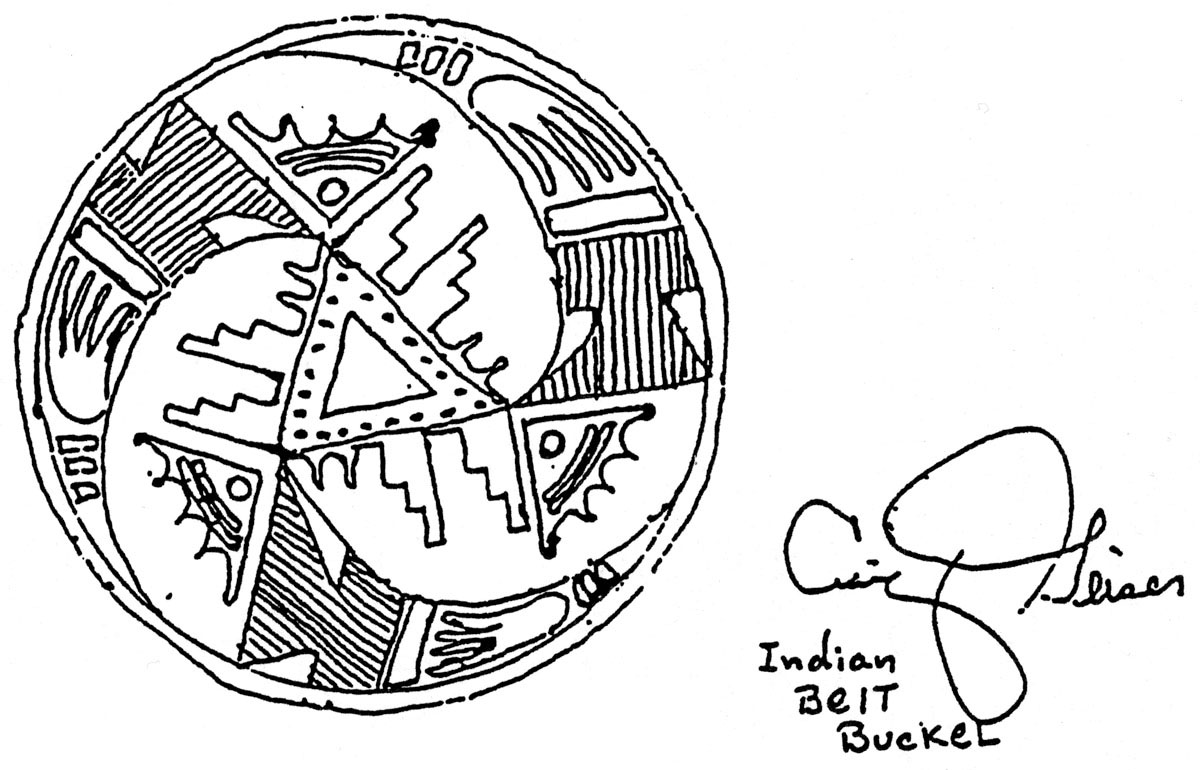

Yet another delusional theme is present in referential delusions: the belief that external events have special meaning for the person. Someone who believes that a song playing in a movie is in some kind of code that has special meaning just for him or her, for instance, is having a referential delusion.

Disorganized Speech

People with schizophrenia can sometimes speak incoherently, although they may not necessarily be aware that other people cannot understand what they are saying. Speech can be disorganized in a variety of different ways. One type of disorganized speech is word salad, which is a random stream of seemingly unconnected words. For example, a patient might say something like, “Pots dog small is tabled.” Another type of disorganized speech involves many neologisms, or words that the patient makes up:

That’s wish-bell. Double vision. It’s like walking across a person’s eye and reflecting personality. It works on you, like dying and going to the spiritual world, but landing in the Vella world.

(Marengo et al., 1985, p. 423)

In this case, “wish-bell” is the neologism; it doesn’t exist, nor does it have an obvious meaning or function as a metaphor.

Grossly Disorganized Psychomotor Behavior

Another positive symptom (and recall that positive in this context means “present,” not “good”) of schizophrenia is grossly disorganized or abnormal psychomotor behavior; the term psychomotor refers to intentional movements, and in this case such behavior is so unfocused and disconnected from a goal that the person cannot successfully accomplish a basic task, or the behavior is inappropriate in the situation. Disorganized behavior can range from laughing inappropriately in response to a serious matter or masturbating in front of others, to being unable to perform normal daily tasks such as washing oneself, putting together a simple meal, or even selecting appropriate clothes to wear.

Catatonia A condition in which a person does not respond to the environment or remains in an odd posture or position, with rigid muscles, for hours.

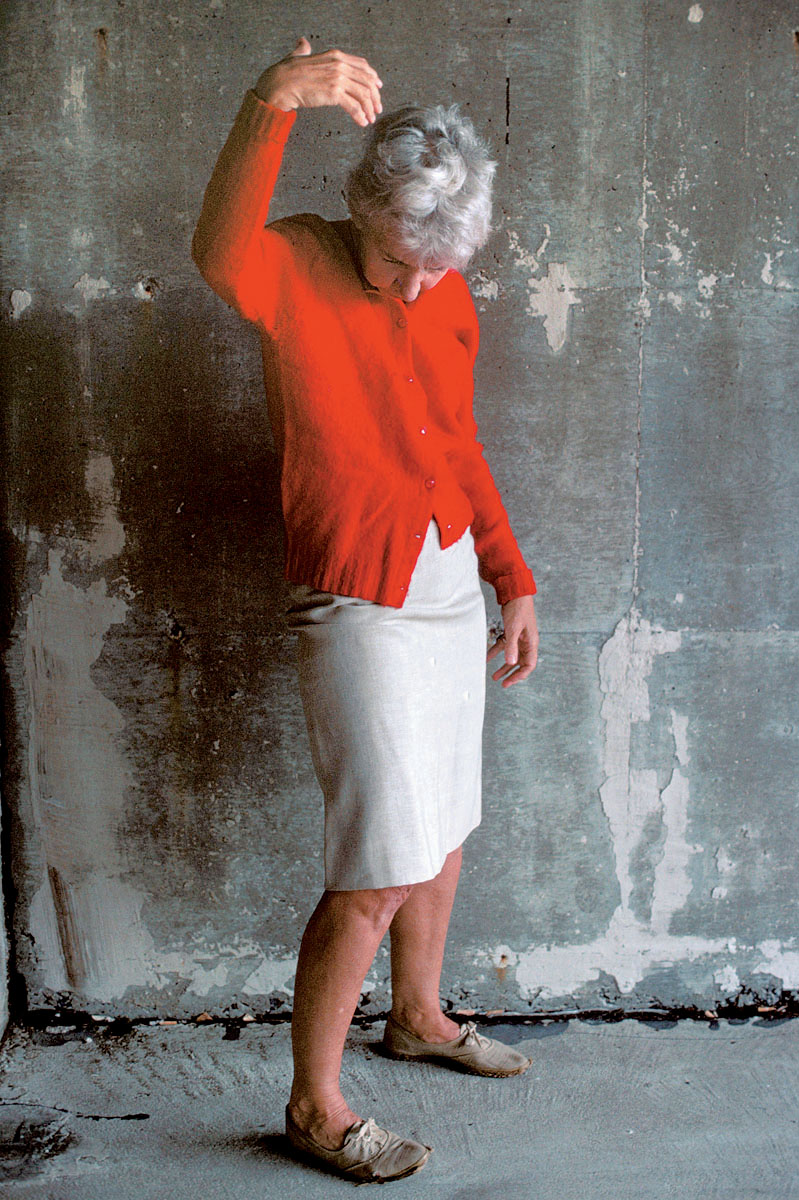

The category of grossly disorganized psychomotor behavior also includes catatonia (also referred to as catatonic behavior), which occurs when a person does not respond to the environment or remains in an odd posture or position, with rigid muscles, for hours. For example, during her early 20s, Iris Genain’s symptoms included standing in the same position for hours each day.

These positive symptoms—hallucinations, delusions, disorganized speech, and grossly disorganized psychomotor behavior—constitute four of the five DSM-5 symptom criteria for schizophrenia; the fifth criterion is any negative symptom (discussed in the following section). Emilio, in Case 12.1, has positive symptoms of schizophrenia.

CASE 12.1 • FROM THE OUTSIDE: Schizophrenia

Emilio is a 40-year-old man who looks 10 years younger. He is brought to the hospital, his twelfth hospitalization, by his mother because she is afraid of him. He is dressed in a ragged overcoat, bedroom slippers, and a baseball cap and wears several medals around his neck. His affect ranges from anger at his mother (“She feeds me shit…what comes out of other people’s rectums”) to a giggling, obsequious seductiveness toward the interviewer. His speech and manner have a childlike quality, and he walks with a mincing step and exaggerated hip movements. His mother reports that he stopped taking his medication about a month ago and has since begun to hear voices and to look and act more bizarrely. When asked what he has been doing, he says, “eating wires and lighting fires.” His spontaneous speech is often incoherent and marked by frequent rhyming and clang associations [speech in which sounds, rather than meaningful relationships, govern word choice].

Emilio’s first hospitalization occurred after he dropped out of school at age 16, and since that time he has never been able to attend school or hold a job. He has been treated with neuroleptics [antipsychotic medications] during his hospitalizations but doesn’t continue to take medication when he leaves, so he quickly becomes disorganized again. He lives with his elderly mother, but sometimes disappears for several months at a time and is eventually picked up by the police as he wanders in the streets. There is no known history of drug or alcohol abuse.

(Spitzer et al., 2002, p–190)

Negative Symptoms

Negative symptoms Symptoms of schizophrenia that are characterized by the absence or reduction of normal mental processes, mental contents, or behaviors.

In contrast to positive symptoms, negative symptoms are characterized by the absence or reduction of normal mental processes, mental contents, or behaviors. DSM-5 specifies a number of negative symptoms: diminished emotional expression and avolition.

Diminished Emotional Expression: Muted Expression

Flat affect A lack of, or considerably diminished, emotional expression, such as occurs when someone speaks robotically and shows little facial expression.

Some people with schizophrenia exhibit diminished emotional expression (sometimes referred to as flat affect), which occurs when a person does not display a large range of emotion, sometimes speaking robotically and seeming emotionally neutral. Such people may not express or convey much information through their facial expressions, body language, tone of voice, and they tend to refrain from making eye contact (although they may smile somewhat and do not necessarily come off as “cold”).

Avolition: Difficulty Initiating or Following Through

Avolition A negative symptom of schizophrenia marked by difficulty initiating or following through with activities.

In movies that portray people with schizophrenia, hospitalized patients are often shown sitting in chairs apparently doing nothing all day, not even talking to others. This portrayal suggests avolition, which consists of difficulty initiating or following through with activities. For example, Hester Genain would often sit for hours, staring into space, and had difficulty beginning her chores.

Other negative symptoms that are less prominent in schizophrenia are:

- Alogia—speaking less than do most other people. A person with alogia will take a while to muster the mental effort necessary to respond to a question.

- Anhedonia—a diminished ability to experience pleasure (see Chapter 5).

- Asociality—disinterest in social interactions.

The sets of positive and negative symptoms in DSM-5 grew out of decades of clinical observations of patients with schizophrenia; these symptoms can generally be observed or can be inferred by a trained researcher or clinician. According to DSM-5, to be diagnosed with schizophrenia, the person must have two out of five symptoms (and at least one symptom must be hallucinations, delusions, or disorganized speech); these symptoms must be present for at least 1 month continuously and at least one symptom must have been present for 6 months; the symptoms must significantly impair functioning. However, research has revealed that cognitive deficits—which are not as easily observed and are not part of the DSM-5 criteria—also play a crucial role in schizophrenia, as we discuss below.

Cognitive Deficits: The Specifics

Research has revealed that cognitive deficits (also called neurocognitive deficits) often accompany schizophrenia (Barch, 2005; Green, 2001). It is not clear whether these deficits cause the disorder, are a necessary or common precondition that makes the disorder more likely to develop, or are a result of the disorder. Specific deficits are found in attention, memory, and executive functioning, and they arise in most people with schizophrenia (Keefe et al., 2005; Wilk et al., 2005).

Deficits in Attention

Cognitive deficits include difficulties in sustaining and focusing attention, which can involve distinguishing relevant from irrelevant stimuli (Gur et al., 2007). One person with schizophrenia recounted: “If I am talking to someone they only need to cross their legs or scratch their heads and I am distracted and forget what I was saying” (Torrey, 2001.

Deficits in Working Memory

Another area of cognitive functioning adversely affected in people with schizophrenia is working memory, which organizes, temporarily retains, and transforms incoming information during reasoning and related mental activities (Baddeley, 1986). For example, if you are trying to remember items you need to buy at the store, you will probably use working memory to organize the items into easy-to-recall categories. People with schizophrenia do not organize information effectively, which indicates that their working memories are impaired.

Deficits in Executive Functioning

Executive functions Mental processes involved in planning, organizing, problem solving, abstract thinking, and exercising good judgment.

Deficits in working memory contribute to problems that people with schizophrenia have with executive functions, which are mental processes involved in planning, organizing, problem solving, abstract thinking, and exercising good judgment (Cornblatt et al., 1997; Erlenmeyer-Kimling et al., 2000; Kim et al., 2004). The problems with executive functioning have far-reaching consequences for cognition in general. For instance, Hester had the most severe symptoms of the Genain quads, and her deficits in executive functioning were prominent much of the time. She had difficulty performing household chores that required multiple steps—such as making mashed potatoes by herself, which required peeling the potatoes, then boiling them, knowing when to take them out of the water, and mashing them with other (measured) ingredients. Obviously, deficits in executive functioning can impair a person’s overall ability to function.

Cognitive Deficits Endure Over Time

Neurocognitive deficits do not necessarily make their first appearance at the same time that the positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia first emerge. For many people who develop schizophrenia, cognitive deficits exist in childhood, well before a first episode of schizophrenia (Cannon et al., 1999; Ott et al., 2002; Torrey, 2002). In addition to predating symptoms of schizophrenia, cognitive deficits often persist after the positive and negative symptoms improve (Hoff & Kremen, 2003; Rund et al., 2004). Thus, at least some of the time these deficits “set the stage” for the disorder but do not actually cause it. However, as we discuss shortly, in some cases such deficits may directly contribute to specific symptoms.

The lives of Genain sisters illustrate both the importance of cognitive deficits and their variety. Hester had the most difficulty academically and was held back in 5th grade because of her poor performance. In contrast, Myra did not exhibit any significant cognitive deficits, and she graduated from high school, held a job, married, and had two children. Nora and Iris had moderate levels of cognitive deficits; they could perform full-time work for periods of time but could not function independently for long stretches (Mirsky & Quinn, 1988; Mirsky et al., 1987, 2000).

Limitations of DSM-5 Criteria

Although the DSM-5 criteria provide a relatively reliable way to diagnose schizophrenia, a number of researchers point to drawbacks of those criteria—both of the specific criteria and of the grouping of positive and negative symptoms (Fauman, 2006; Green, 2001). A more diagnostically and prognostically relevant set of symptoms, these researchers suggest, would focus on the extent of cognitive deficits and the breadth and severity of the DSM-5 symptoms.

Absence of Focus on Cognitive Deficits

Cognitive deficits are not specifically addressed in the DSM-5 criteria, despite their importance. Although the DSM-5 set of positive symptoms includes disorganized speech and grossly disorganized psychomotor behavior (see TABLE 12.1), research suggests that these two symptoms together form an important cluster, independent of hallucinations and delusions. This cluster apparently reflects specific types of underlying cognitive deficits, which clearly contribute to disorganized thinking. For instance, cognitive deficits can cause thoughts to skip from one topic to another, topics that are related to each other only tangentially if at all. (This process is referred to as a loosening of associations.) Thus, disorganized speech arises from disorganized thinking. Similarly, grossly disorganized psychomotor behavior, such as laughing at a funeral or putting on four pairs of underwear, can occur because the person’s cognitive deficits prevent him or her from organizing social experiences into categories covered by general rules of behavior or conventions.

Cognitive deficits can also lead to unusual social behavior or asociality. As we’ll discuss in more detail later, people with schizophrenia may be socially isolated and avoid contact with others because such interactions can be overwhelming or confusing. People with schizophrenia can have difficulty understanding the usual, unspoken rules of social convention. Also, even after an episode of schizophrenia has abated, they may not understand when someone is irritated because they do not notice or correctly interpret the other person’s facial expression or tone of voice (which are types of cognitive deficits; Clark et al., 2013). When irritation erupts into anger, it can seem to come out of the blue, frightening and overwhelming people with schizophrenia. So, they may try to tread a safer path and avoid others as much as possible. In turn, the poor social skills and social isolation are related to an impaired ability to work (Dickinson et al., 2007). The disorganized behavior, asociality, and poor social skills, and perhaps avolition, all are indicators of underlying cognitive deficits (Farrow et al., 2005).

Deficit/Nondeficit Subtypes

Researchers make a distinction between patients diagnosed with schizophrenia who have significant cognitive deficits and those who do not (Horan & Blanchard, 2003). To be considered to have the deficit subtype, a patient must have severe neurocognitive deficits in attention, memory, and executive functioning, as well as the positive and negative symptoms that are manifestations of these deficits, such as disorganized speech and grossly disorganized psychomotor behavior. Such patients are generally more impaired than are other patients with schizophrenia, and their symptoms are less likely to improve with currently available treatments. They may be more impaired, at least in part, because parts of their brains do not work together normally; neuroimaging results show that people with the deficit subtype of schizophrenia (but not those who have the nondeficit subtype) have abnormalities in their “white matter tracts”—sets of axons that connect neurons (Voineskos et al., 2013). (They are white because they are covered with the fatty insulator substance myelin.)

To be considered to have the nondeficit subtype, a patient must have positive symptoms, such as hallucinations and delusions, in conjunction with relatively intact cognitive functioning. People with this subtype are generally less impaired, and they have a better prognosis (McGlashan & Fenton, 1993).

Distinguishing Between Schizophrenia and Other Disorders

Positive or negative symptoms may arise in schizophrenia or in the context of other disorders. Clinicians and researchers must determine whether the positive or negative symptoms reflect schizophrenia, another disorder, or, in some cases, schizophrenia and another disorder.

Psychotic Symptoms in Schizophrenia, Mood Disorders, and Substance-Related Disorders

Other psychological disorders, most notably mood disorders and substance-related disorders, may involve symptoms such as hallucinations and delusions. (Mood disorders with psychotic features are discussed in Chapter 5, and substance-induced hallucinations and delusions are discussed in Chapter 9.) The content of these psychotic symptoms is usually consistent with the characteristics of the mood disorder or substance-related disorder, and the psychotic symptoms only arise during a mood episode or with substance use or withdrawal.

For example, people with mania may become psychotic, developing grandiose delusions about their abilities. Psychotic mania is distinguished from schizophrenia by the presence of other symptoms of mania—such as pressured speech or little need for sleep.

Similarly, psychotically depressed people may have delusions or hallucinations; the delusions usually involve themes of the depressed person’s worthlessness or the “badness” of certain body parts (e.g., “My intestines are rotting”). Some negative symptoms of schizophrenia can be difficult to distinguish from symptoms of depression: People with schizophrenia or depression may show little interest in activities, hardly speak at all, give minimal replies to questions, and avoid social situations. As noted in TABLE 12.2, although both of these disorders may involve similar outward behaviors, the behaviors arise from different causes. In general, people with schizophrenia but not depression do not have other symptoms of depression, such as changes in weight or sleep or feelings of worthlessness and inappropriate guilt (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Of course, people with schizophrenia may develop comorbid disorders, such as depression.

| Behavioral symptoms | Causes in depression | Causes in schizophrenia |

|---|---|---|

| Little or no interest in activities, staring into space for long periods of time | Lack of pleasure in activities (anhedonia), difficulty making decisions | Difficulty initiating behavior (avolition) |

| Short or “empty” replies to questions | Lack of energy | Difficulty organizing thoughts to speak |

| Social isolation | Lack of energy, anhedonia, feeling undeserving of companionship | Feeling overwhelmed by social situations, lack of social skills |

Finally, substance-related disorders can lead to delusions (see Chapter 9), such as the persecutory delusions that arise from chronic use of stimulants. Substances (and withdrawal from them) can also induce hallucinations, such as the tactile hallucinations that can arise with cocaine use (e.g., the feeling that bugs are crawling over a person’s arms). Determining the correct diagnosis can be particularly challenging when a person has more than one disorder and the symptoms of those disorders appear similar.

Other Psychotic Disorders

Although mood disorders and substance-related disorders may involve psychotic symptoms, the diagnostic criteria for these two categories of disorders do not specifically require the presence of psychotic symptoms. In contrast, the criteria for the disorders collectively referred to as psychotic disorders specifically require the presence of symptoms related to psychosis; these disorders are part of a spectrum, related to each other in their symptoms and risk factors but differing in their specific constellations of symptoms, duration, and severity.

Schizophreniform and Brief Psychotic Disorders

In some cases, a person’s symptoms may meet most, but not all, of the criteria for a diagnosis of schizophrenia. The person clearly suffers from some psychotic symptoms and has significant difficulty in functioning as a result of his or her psychological problems. However, the impaired functioning hasn’t been present for the minimum 6-month duration required for a diagnosis of schizophrenia. Two disorders fall into this class, depending on the specifics of the symptoms and their duration.

Schizophreniform disorder A psychotic disorder characterized by symptoms that meet all the criteria for schizophrenia except that the symptoms have been present for only 1–6 months, and daily functioning may or may not have declined over that period of time.

Schizophreniform disorder is the diagnosis given when a person’s symptoms meet all the criteria for schizophrenia except that symptoms have been present for between 1 and 6 months (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). In addition, daily functioning may or may not have declined over that period of time. If the symptoms persist for more than 6 months (and daily functioning has significantly declined), the diagnosis shifts to schizophrenia.

Brief psychotic disorder A psychotic disorder characterized by the sudden onset of positive or disorganized symptoms that last between 1 day and 1 month and are followed by full recovery.

In contrast, brief psychotic disorder refers to the sudden onset of hallucinations, delusions, or disorganized speech or behavior that last between 1 day and 1 month and are followed by full recovery (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). For this diagnosis, no negative symptoms should be present during the episode. Rather, brief psychotic disorder is characterized by intense emotional episodes and confusion, during which the person may be so disorganized that he or she cannot function safely and independently; he or she also has an increased risk of suicide during the episode. Once recovered, people who had this disorder have a good prognosis for full recovery (Pillman et al., 2002).

Schizoaffective Disorder

Schizoaffective disorder A psychotic disorder characterized by the presence of both schizophrenia and a depressive or manic episode.

Schizoaffective disorder is characterized by the presence of both schizophrenia and a depressive or manic episode (see Chapter 5). For this diagnosis, the mood episode must be present during most of the period when the symptoms of schizophrenia are present; in addition, delusions or hallucinations must be present for at least 2 weeks when there is no mood episode. Because schizoaffective disorder involves mood episodes, negative symptoms such as flat affect are less common, and the diagnosis is likely to be made solely on the basis of positive symptoms. Because of their mood episodes, people with schizoaffective disorder are at greater risk for committing suicide than are people with schizophrenia (Bhatia et al., 2006; De Hert et al., 2001). The prognosis for recovery from schizoaffective disorder is somewhat better than that for recovery from schizophrenia, particularly when stressors or events clearly contribute to the disorder (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Jeff Kravitz/FilmMagic/Getty Images

Delusional Disorder

Delusional disorder A psychotic disorder characterized by the presence of delusions that have persisted for more than 1 month.

A person is diagnosed with delusional disorder when the sole symptom is delusional beliefs—such as believing that someone is following you when they actually are at work on the other side of town—that have persisted for at least 1 month. Clinicians and researchers have identified the following types of delusions in delusional disorder (American Psychiatric Association, 2013):

- Erotomanic. The belief that another person is in love with the patient. This delusion usually focuses on romantic or spiritual union rather than sexual attraction.

- Grandiose. The belief that the patient has a great (but unrecognized) ability, talent, or achievement.

- Persecutory. The belief that the patient is being spied on, drugged, harassed, or otherwise conspired against.

- Somatic. The false belief that something is wrong with the body (such as insects on the skin) and these delusions are not considered a symptom of another psychological disorder, such as obsessive-compulsive disorder (Chapter 7) or body dysmorphic disorder (Chapter 7).

- Jealous. The belief that the patient’s romantic partner is unfaithful. This belief is based on tiny amounts of “evidence,” such as the partner’s arriving home a few minutes late.

People with delusional disorder may appear normal when they are not talking about their delusions. Their behavior may not be particularly odd nor their functioning otherwise impaired. Henry Genain, the quads’ father, exhibited some signs of delusional disorder of the jealous type: Soon after he met Maud, the Genains’ mother, he asked her to marry him, but she refused. He pestered her for months, threatening that if she didn’t marry him, neither of them would live to marry anyone else. On multiple occasions, he threatened to kill himself or her. After she consented to marry him (because his family begged her to), he didn’t want her to socialize with anyone else, including her family. His jealousy was so extreme that he didn’t want her to go out of the house because people walking down the street might smile at her. When the quads were 7 years old, Mrs. Genain thought of leaving Henry, but he told her, “If you leave me, I will find you where you go and I’ll kill you” (Rosenthal, 1963. She believed him and stayed with him.

One extremely unusual and rare presentation of delusional symptoms involves a shared delusion among two or more people (sometimes referred to as folie à deux, which is French for “paired madness”). (Technically, this is an “other” psychotic disorder because it doesn’t meet the criteria for any specific disorder in the category of psychotic disorders.) With this variant, a person develops delusions as a result of his or her close relationship with another person who has delusions as part of a psychotic disorder. The person who had the disorder at the outset is referred to as the primary person and is usually diagnosed with schizophrenia or delusional disorder. The delusions of the primary person may be shared by more than one other person, as can occur in families when the primary person is a parent. When the primary person’s delusions subside, the other person’s shared delusions may or may not also subside.

Schizotypal Personality Disorder

Eccentric behaviors and difficulty with relationships are the hallmarks of schizotypal personality disorder, discussed in more detail with the other personality disorders in Chapter 13. A person with schizotypal personality disorder may have very few if any close friends, may feel that he or she doesn’t fit in, and may experience social anxiety. Schizotypal personality disorder, unlike schizophrenia, does not involve psychotic symptoms. Although schizotypal personality disorder is thus not technically a psychotic disorder, some research suggests that it may in fact be a milder form of schizophrenia (Dickey et al., 2002); for this reason, in DSM-5 the disorder is placed within the schizophrenia spectrum as well as within the personality disorders; we have listed its criteria in Chapter 13 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). With this personality disorder, problems in relationships may become evident by early adulthood, marked by discomfort when relating to others as well as by being stiff or inappropriate in relationships. TABLE 12.3 summarizes the key features of schizophrenia spectrum and psychotic disorders.

| Psychotic disorder | Features |

|---|---|

| Schizophrenia | At least two symptoms—one of which must be delusions, hallucinations, or disorganized speech—for a minimum of 1 month; continuous symptoms for at least 6 months, during which time the person has impaired functioning in some area(s) of life. Note: Criteria are listed in TABLE 12.1. |

| Schizophreniform disorder | Symptoms meet all the criteria for schizophrenia except that the symptoms have been present for only 1–6 months; daily functioning may or may not have declined over that period of time. |

| Brief psychotic disorder | The sudden onset of positive symptoms, which persist between a day and a month, followed by a full recovery. No negative symptoms are present during the episode. |

| Schizoaffective disorder | Symptoms meet the criteria for both schizophrenia and mood disorder, with symptoms of schizophrenia present for at least 2 weeks without symptoms of a mood disorder, and a mood episode present during most of the period when the symptoms of schizophrenia are present. Negative symptoms of schizophrenia are less common with this disorder. |

| Delusional disorder | The presence of delusions that persist for at least 1 month, without a diagnosis of schizophrenia. |

The various psychotic disorders have in common the presence of hallucinations and/or delusions. Although schizotypal personality disorder is not a psychotic disorder (because hallucinations and delusions are absent), this personality disorder is considered to be on the spectrum of schizophrenia-related disorders.

CURRENT CONTROVERSY

Attenuated Psychosis Syndrome: The Diagnosis That Wasn’t

Attenuated psychosis syndrome is a diagnosis that was proposed for inclusion in DSM-5 but that did not make it in. This condition is defined by “attenuated” (that is, reduced or weakened) psychotic symptoms of psychosis. For example, rather than paranoid delusions, someone may be generally mistrustful, and rather than hearing voices, someone may hear rumblings or murmurs.

On the one hand, proponents of adding this diagnosis thought it would help detect and treat cases of psychotic disorders before they became full blown; therefore, the alternative name for this disorder was psychotic risk syndrome (McFarlane et al., 2012; McGorry, 2010, 2012). Psychotic episodes can create long-lasting disturbances in brain activation, cognitive functioning, and social relations; the proponents of this diagnosis hoped that identifying and intervening earlier might reduce the likelihood that “at risk” cases would become full-blown schizophrenia (McGorry et al., 2002; Wade et al., 2006).

On the other hand, critics charge that identifying people whose symptoms don’t meet the criteria for positive symptoms of schizophrenia labels them as “psychotic” when they aren’t and might never become so (Frances, 2013; Schultze-Lutter et al., 2013; Tsuang et al., in press). Furthermore, critics argue that treating such people with antipsychotic medications—which have significant and serious side effects—when the symptoms don’t warrant it would be inappropriate.

CRITICAL THINKING If this diagnosis—or some version of it—is adopted in the future, how can we reduce the likelihood that this diagnosis will be used to overlabel and overtreat people with attenuated symptoms?

(James Foley, College of Wooster)

Schizophrenia Facts in Detail

In this section we discuss additional facts about schizophrenia.

Prevalence

The world over—from China or Finland to the United States or New Guinea—approximately 1% of the population will develop schizophrenia (Gottesman, 1991; Perälä et al., 2007).

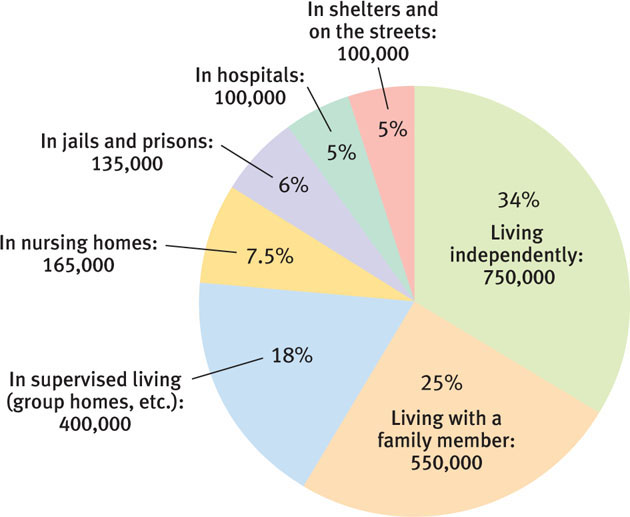

Schizophrenia is one of the top five causes of disability among adults in developed nations, ranking with heart disease, arthritis, drug use, and HIV (Murray & Lopez, 1996). In the United States, about 5% of people with schizophrenia (about 100,000 people) are homeless, 5% are in hospitals, and 6% are in jail or prison (Torrey, 2001). In contrast, 34% of people with this disorder live independently (see Figure 12.1).

Comorbidity

Over 90% of people with schizophrenia also suffer from at least one other psychological disorder (and, as the numbers below suggest, often two or more other disorders; Sands & Harrow, 1999). Substance-related disorders, mood disorders, and anxiety disorders are the most common comorbid disorders:

- Mood disorders. Approximately 50% of people with schizophrenia also have some type of mood disorder, most commonly depression (Buckley et al., 2009; Sands & Harrow, 1999). As noted earlier, according to DSM-5, some of these people may have schizoaffective disorder.

- Anxiety disorder. Almost half of people with schizophrenia also have panic attacks (Goodwin et al., 2002) and anxiety disorders (Cosoff & Hafner, 1998).

- Substance use disorders. Up to 60% of people with schizophrenia have a substance abuse problem that is not related to tobacco (Swartz et al., 2006). Moreover, 90% of those with schizophrenia smoke cigarettes (Regier et al., 1990), and they tend to inhale more deeply than do other smokers (Tidey et al., 2005).

Researchers have also noted that even before their positive symptoms emerged, some people with schizophrenia abused drugs, particularly nicotine (cigarettes), marijuana, amphetamines, phencyclidine (PCP), mescaline, and lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) (Bowers et al., 2001; Weiser et al., 2004). For example, a study of Swedish males found that those who used marijuana in adolescence were more likely later to develop schizophrenia. The more a person used marijuana, the more likely he or she was to develop schizophrenia, particularly if the drug was used more than 50 times (Moore et al., 2007; Zammit et al., 2002).

However, keep in mind that the correlation between using marijuana and subsequent schizophrenia does not show that the drug causes schizophrenia. For example, perhaps marijuana use leads to schizophrenic symptoms only in those who were likely to develop the disorder anyway, or a predisposition to develop schizophrenia also might make drug use attractive (Kahn et al., 2011). It is also possible that marijuana “tips the scales” in those who are vulnerable but who would not develop schizophrenia if they did not use the drug (Large et al., 2011). Or perhaps some other factor affects both substance abuse and subsequent schizophrenia (Bowers et al., 2001). Researchers do not yet know enough to be able to choose among these possibilities, and true experiments designed to investigate them would obviously be unethical.

Course

Prodromal phase The phase that is between the onset of symptoms and the time when the minimum criteria for a disorder are met.

Typically, schizophrenia develops in phases. In the premorbid phase, before symptoms develop, some people may display personality characteristics or cognitive deficits that later evolve into negative symptoms (MacCabe et al., 2013). However, it is important to note that the vast majority of people who are odd or have eccentric tendencies do not develop schizophrenia. During the prodromal phase, which is between the onset of symptoms and the time when the minimum criteria for a disorder are met. In the active phase, a person has full-blown positive (and possibly negative) symptoms that meet the criteria for the disorder. If the positive symptoms have subsided but negative symptoms persist, the full criteria for schizophrenia are no longer met; the person can be said to be in the residual phase, which indicates that there is a residue of (negative) symptoms but the pronounced positive symptoms have faded away. As shown in TABLE 12.4, over time, the person may fully recover, may have intermittent episodes, or may develop chronic symptoms that interfere with normal functioning.

Active phase The phase of a psychological disorder (such as schizophrenia) in which the person exhibits symptoms that meet the criteria for the disorder.

| 10 years later | 30 years later | |

|---|---|---|

| Completely recovered | 25% | 25% |

| Much improved, relatively independent | 25% | 35% |

| Improved but requiring extensive support network | 25% | 15% |

| Hospitalized, unimproved | 15% | 10% |

| Dead, mostly by suicide | 10% | 15% |

| Source: Torrey, 2001, p. 130. | ||

Although most of the Genain sisters were not able to live independently, like many other people with schizophrenia (Levine et al., 2011), the symptoms of the Genain sisters generally improved (Mirsky et al., 2000). Iris and Nora were able to work part time as volunteers; in their 40s and beyond, these two sisters were able to live outside a hospital setting (Mirsky et al., 2000; Rosenthal, 1963).

Gender Differences

Men are more likely to develop schizophrenia than are women; 1.4 men develop the disorder for every woman (McGrath, 2006). Moreover, men are more likely to develop the disorder in their early 20s whereas women are more likely to develop the disorder in their late 20s or later. Compared to men, women usually have fewer negative symptoms (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Maric et al., 2003) and more mood symptoms (Maurer, 2001), and they are less likely to have substance abuse problems or to exhibit suicidal or violent behavior (Seeman, 2000). Moreover, women generally function at higher levels before their illness develops.

Culture

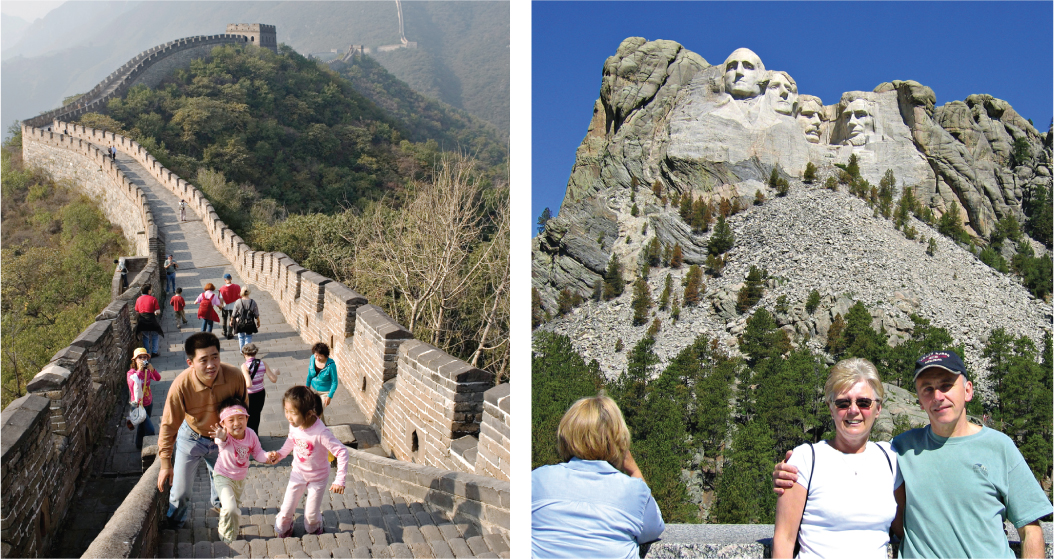

GETTING THE PICTURE

JL Images/Alamy

Two findings bear on the role of culture and schizophrenia. First, across various countries, schizophrenia is more common among people in urban areas and lower socioeconomic classes than among people in rural areas and higher socioeconomic classes (Freeman, 1994; Mortensen et al., 1999), as we’ll discuss in more detail later in this chapter. Moreover, there are ethnic differences in prevalence rates in the United States: Blacks are twice as likely as Whites or Latinos to be diagnosed with schizophrenia (Dassori et al., 1995; Keith et al., 1991). These prevalence differences may reflect the influence of a variety of moderating variables, such as biases in the use of certain diagnostic categories for different ethnic groups.

Second, people with schizophrenia in non-Western countries are generally better able to function in their societies than are their Western counterparts, and thus they have a better prognosis. We’ll discuss possible reasons for this finding in the Understanding Schizophrenia section on social factors.

TABLE 12.5 provides a summary of facts about schizophrenia.

| Prevalence |

|

| Comorbidity |

|

| Onset |

|

| Course |

|

| Gender Differences |

|

| Cultural Differences |

|

| Source: Unless otherwise noted, citations for above table are: American Psychiatric Association, 2000, 2013. |

Prognosis

In general, the long-term prognosis for schizophrenia follows the rule of thirds:

- one third of patients improve significantly;

- one third basically stay the same, having episodic relapses and some permanent deficits in functioning, but are able to hold a “sheltered” job—a job designed for people with mild to moderate disabilities; and

- one third become chronically and severely disabled by their illness.

TABLE 12.6 summarizes factors associated with a better prognosis in Western countries. However, this table does not indicate a crucial fact about the prognosis for people with schizophrenia: Over the course of their lives, people with schizophrenia are more likely than others to die by suicide or to be victims of violence. In what follows we examine these risks in greater detail.

People with schizophrenia who significantly improve often have one or more of the following characteristics:

|

| Sources: 1991; Fenton & McGlashan, 1994; Green, 2001. |

Suicide

People with schizophrenia have a higher risk of dying by suicide than do other people: As TABLE 12.4 shows, as many as 10–15% of people with schizophrenia commit suicide (Caldwell & Gottesman, 1990; Siris, 2001). Those with paranoid symptoms are at the highest risk for suicide. Perhaps paradoxically, patients at risk for committing suicide are those who are most likely to be aware of their symptoms: They have relatively few negative symptoms but pronounced positive symptoms; they tend to be highly intelligent, have career goals, are aware of their deterioration, and have a pattern of relapsing and then getting better, with many episodes; and—like other people who die by suicide—they are more likely to be male than female (Fenton, 2000; Funahashi et al., 2000; Siris, 2001). Ironically, some of these factors—a high level of premorbid functioning, few negative symptoms, and an awareness of the symptoms and their effects—are associated with a better prognosis (see TABLE 12.6). As researchers have identified these risk factors, they have used them to focus suicide prevention efforts.

Violence

A small percentage of people with schizophrenia commit violent acts. Risk factors associated with violent behavior include being male, having comorbid substance abuse, not taking medication, and having engaged in criminal behavior or having had psychopathic tendencies before schizophrenia developed (Hunt et al., 2006; Monahan et al., 2001; Skeem & Mulvey, 2001; Tengström et al., 2001).

Rather than being violent, people with schizophrenia are much more likely to be victims of violence. One survey found that almost 20% of people with a psychotic disorder had been victims of violence in the previous 12 months. Those who were more disorganized and functioned less well were more likely to have been victimized (Chapple et al., 2004), perhaps because their impaired functioning made them easier “marks” for perpetrators.

Thinking Like A Clinician

Suppose you are a mental health clinician working in a hospital emergency room in the summer; a woman is brought in for you to evaluate. She’s wearing a winter coat, and in the waiting room, she talks—or shouts—to herself or an imaginary person. You think that she may be suffering from schizophrenia. What information would you need in order to make that diagnosis? What other psychological disorders could, with only brief observation, appear similar to schizophrenia?