14.3 Specific Learning Disorder: Problems with the Three Rs

Richie Enriquez’s older brother, Javier, is in the 4th grade. Javier’s teacher has noted that his reading ability doesn’t seem up to what it should be. Javier is a bright boy, but when the students take turns reading aloud, Javier isn’t able to read as well as his classmates. Javier generally has things he wants to say in class—sometimes raising his hand so high and waving it so energetically that he practically hits the heads of nearby children. His comments often show a keen understanding of what the teacher has said, and his apparent reading problem seems to be at odds with his general intelligence. Could Javier have a learning disorder?

What Is Specific Learning Disorder?

Specific learning disorder A neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by skills well below average in reading, writing, or math, based on the expected level of performance for the person’s age, general intelligence, cultural group, gender, and education level.

Specific learning disorder is characterized by well below average skills in reading, writing, or math, based on the expected level of performance for the person’s age, general intelligence, cultural group, gender, and education level. For the diagnosis to be made, the deficits must significantly interfere with school or work performance or daily living (when supports and services are not provided). TABLE 14.6 lists the DSM-5 criteria for specific learning disorders.

|

| Reprinted with permission from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, (Copyright ©2013). American Psychiatric Association. All Rights Reserved. |

DSM-5 lists three categories of specific learning disorder (American Psychiatric Association, 2013):

- Reading, often referred to as dyslexia, characterized by difficulty with accuracy, speed, or comprehension when reading, to the point that the difficulty interferes with academic achievement or activities of daily functioning that involve reading.

Dyslexia A learning disorder characterized by difficulty with reading accuracy, speed, or comprehension that interferes with academic achievement or activities of daily functioning that involve reading.

- Written expression, characterized by poor spelling, significant grammatical or punctuation mistakes, or problems with writing in a clear and organized manner.

- Mathematics, sometimes referred to as dyscalculia, characterized by difficulty understanding the relationships among numbers, memorizing arithmetic facts, accurately and fluently making calculations, and reasoning effectively about math problems.

Nancy, in Case 14.3, has a specific learning disorder that involves reading. Additional facts about specific learning disorder are presented in TABLE 14.7.

| Prevalence |

|

| Onset |

|

| Comorbidity |

|

| Course |

|

| Gender Differences |

|

| Cultural Differences |

|

| Source: Unless otherwise noted, the source for information is American Psychiatric Association, 2013. |

CASE 14.3 • FROM THE INSIDE: Specific Learning Disorder (Reading)

Nancy Lelewer, author of Something’s Not Right: One Family’s Struggle With Learning Disabilities (1994), describes what having a learning disorder was like for her:

I began public elementary school in the early 1940s…. Reading was taught exclusively by a whole-word method dubbed “Look, Say” because of its reliance on recognizing individual words as whole visual patterns, rather than focusing on letters or letter patterns. In first grade, I listened to my classmates, and when it was my turn, I read the pictures, not the words, “Oh Sally! See Spot. Run. Run. Run.” When we were shown flash cards and responded in unison to them, I mouthed something.

Then came our first reading test. The teacher handed each student a sheet of paper, the top half of which was covered with writing. I looked at it and couldn’t read a word…. The room grew quiet as the class began to read.

As I stared at the page, total panic gripped me. My insides churned, and I began to perspire as I wondered what I was going to do. As it happened, the boy who sat right in front of me was the most able reader in my class. Within a few minutes, he had completed the test and had pushed his paper to the front of his desk, which put it in my full view…. [I copied his answers and] passed the test and was off on a track of living by my wits rather than being able to read.

The “wits track” is a nerve-wracking one. I worried that the boy would be out sick on the day we had a reading test. I worried that the teacher might change the location of my desk. I worried that I would get caught copying another student’s answers. I knew that something was wrong with me, but I didn’t know what. Why couldn’t I recognize words that my classmates read so easily?

(pp. 15–17)

Specific learning disorder may cast a long shadow over many areas of life for many years. People with a learning disorder are 50% more likely to drop out of school than are people in the general population, and work and social relationships are more likely to suffer (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). These people are also more likely than average to suffer from poor self-esteem.

Understanding Specific Learning Disorder

Like intellectual disability and ASD, specific learning disorder is primarily caused by neurological factors. But psychological and social factors also play a role.

Neurological Factors

Among the three domains of specific learning disorder, dyslexia has been studied the most extensively. Evidence is growing that impaired brain systems underlie this disorder and that genes contribute to these impaired systems.

Brain Systems

In most forms of dyslexia, the brain systems involved in auditory processing do not function as well as they should (Marshall et al., 2008; Ramus et al., 2003). The results of many neuroimaging studies have converged to identify a set of brain areas that is disrupted in people who have dyslexia (Shaywitz et al., 2006). First, two rear areas in the left hemisphere are not as strongly activated during reading tasks in people with dyslexia as they are in people who read normally. One of these areas is involved in converting visual input to sounds (Friedman et al., 1993), and the other area, at the junction of the parietal and occipital lobes, appears to be used to recognize whole words, based on their visual forms (Cao et al., 2006; McCandliss et al., 2003). Second, two other brain areas are more strongly activated in people with dyslexia than in people who read normally. These areas appear to be used in carrying out compensatory strategies, which rely on stored information instead of the vision–sound conversion process.

Genetics

A specific learning disorder in reading is moderately to highly heritable (Hawke et al., 2006; Schulte-Körne, 2001), and at least four specific genes are thought to affect the development of this disorder (Fisher & Francks, 2006; Marino et al., 2007). Some of these genes affect how neurons become connected during brain development (Rosen et al., 2007), and some may affect the functioning of neurons or influence the activity of neurotransmitters (Grigorenko, 2001).

Psychological Factors

Some children with a specific learning disorder succeed in situations where others fail. For example, they might persevere in solving a difficult puzzle. Why? In order to address this question, researchers interviewed college students with a specific learning disorder and asked about their experiences as young children (Miller, 2002). These people reported a number of psychological factors that played important roles in shaping their motivation to overcome their disorder; these factors included self-determination, recognizing particular areas of strength, identifying the learning disability, and developing ways to cope with it.

Social Factors

Social factors play a role in shaping motivation to persist in the face of a learning disorder (Miller, 2002). Other people, such as parents and teachers, were important in supporting and encouraging children who later succeeded in overcoming their learning disabilities. In addition, certain social environments—such as attending a low-quality school or coming from a disadvantaged family—apparently can contribute to at least some forms of dyslexia (Shaywitz et al., 2006; Wadsworth et al., 2000).

Treating Dyslexia

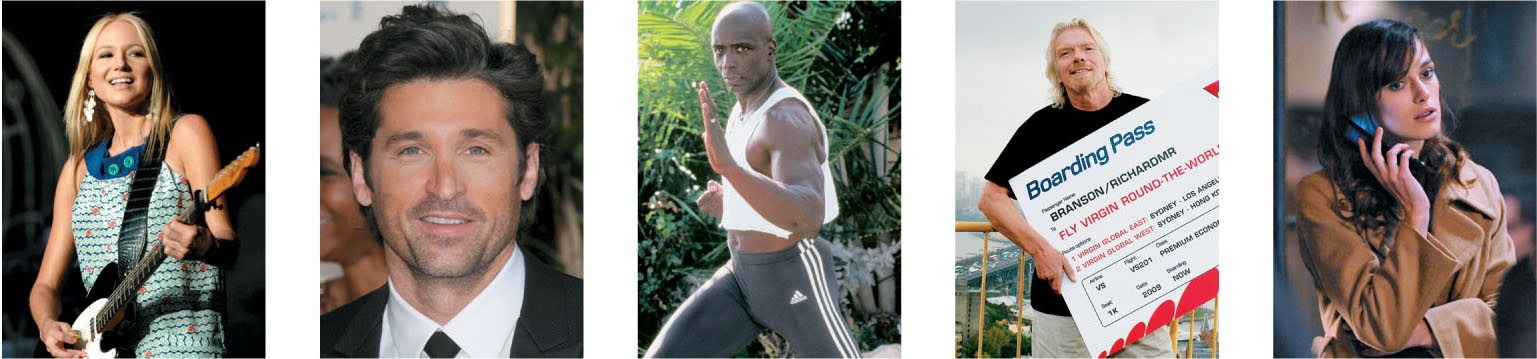

Steve Granitz/WireImage/Getty Images

© Neal Preston/Corbis

Don Arnold/WireImage/Getty Images

James Devaney/WireImage/Getty Images

As with the other childhood disorders discussed thus far in this chapter, neurological factors generally are not directly targeted for treatment (unless the treatment is for a comorbid disorder). Dyslexia has been the subject of the most research on treatment, and researchers have reported successful interventions for this disorder.

One technique for helping people with dyslexia is phonological practice, which consists of learning to divide words into individual sounds and to identify rhyming words. Another technique focuses on teaching children the alphabetic principle, which governs the way in which letters signal elementary speech sounds (Shaywitz et al., 2004). In fact, various forms of training using these techniques have been shown not only to improve performance but also to improve the functioning of brain areas that were impaired prior to the training (Gaab et al., 2007; Simos et al., 2007; Temple et al., 2003).

Thinking Like A Clinician

Nikhil recently graduated from college and is about to start working in the Teach for America program. He’s been assigned to teach at an inner-city school. Nikhil was a math major in college and doesn’t know much about learning disabilities. However, he was a peer tutor in college and saw that some people had a really hard time understanding different elements of math. Based on what you’ve read, what information should Nikhil know (and hopefully will be taught as part of his training) about specific learning disorder before he walks into a classroom, and why should he learn this material?