15.3 Dementia (and Mild Versus Major Neurocognitive Disorders)

Mrs. B. seemed to have memory problems. But memory was not the only aspect of her cognitive functioning that had declined. During neuropsychological testing, “the principal areas of difficulty on [certain] tests were in mental control, as evidenced by tangential and repetitive speech; psychomotor slowing [in this case, slow movements based on mental processes, not reflexes]; and reduced flexibility in thought and action” (La Rue & Watson, 1998. Some of these difficulties are characteristic of dementia. Could Mrs. B. have dementia?

In this section we focus on dementia: what it is, what neurological factors give rise to it, and what treatments are available for it.

What Is Dementia?

Although not a DSM-5 disorder, dementia is the general term for a set of neurocognitive disorders characterized by deficits in learning new information or recalling information already learned plus at least one of the following types of impaired cognition:

- Aphasia. In dementia, problems with using language often appear as overuse of the words thing and it because of difficulty remembering the correct specific words.

- Apraxia. Problems with executing motor tasks (even though there isn’t anything wrong with the appropriate muscles, limbs, or nerves). Such problems can lead to difficulties in dressing oneself and eating, at which point self-care becomes impossible.

- Agnosia. People with dementia may not recognize common objects—or friends, family members, or even their own face.

- Executive function problems. These patients may also have difficulties in planning, initiating, organizing, abstracting, and sequencing or even in recognizing that one has memory problems. (These problems arise primarily in dementia that affects the frontal lobes.) These deficits can make it impossible to meet the demands of daily life. Mrs. B. had difficulties in tasks that required executive functions.

Dementia A set of neurocognitive disorders characterized by deficits in learning new information or recalling information already learned plus at least one other type of cognitive impairment.

We discussed aphasia, apraxia, and agnosia earlier, in the context of effects of brain damage on cognition. Unlike the effects caused by a stroke or a head injury, however, dementia is not caused by an isolated incident, nor do the deficits emerge quickly. Rather, they arise over a period of time, as brain functioning degrades; symptoms of dementia often change over time, typically becoming progressively worse (referred to as a progressive dementia), but sometimes remaining static or in a minority of cases even reversing course. Dementia can arise as a result of a medical disease, such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases, but it is the dementia, not the medical disease itself, that is considered to be a neurocognitive disorder in DSM-5. In the United States, one estimate is that caring for people with dementia costs as much as caring for those with heart disease or cancer—up to $2.15 billion per year (Hurd et al., 2013). Most people with dementia are over 65 years old when symptoms emerge, termed late onset. When symptoms begin before age 65, the disorder is said to have early onset. Early onset, particularly before age 50, is rare and is usually hereditary (Ikeuchi et al., 2008).

Mild and Major Neurocognitive Disorders

In DSM-5, dementia is not a disorder; rather, people with dementia or other adult-onset cognitive deficits (such as difficulties with language) are diagnosed with either mild or major neurocognitive disorder (discussed below), depending on the person’s symptoms and ability to function independently. Specifically, DSM-5 specifies six cognitive domains in which deficits may occur for these disorders:

- Complex attention—such as focusing and sustaining attention,

- Executive functions—such as planning and decision making,

- Learning and memory—such as learning new skills and remembering them,

- Language—such as speaking or understanding,

- Perceptual-motor—such as hand–eye coordination,

- Social cognition—such as recognizing emotions in others.

Impaired cognitive functioning can lead many patients to become easily overwhelmed or confused, causing them to be agitated. The confusion or agitation may then lead a patient to become violent, which can make it difficult or potentially dangerous for the patient to remain living at home with family members—and hence the patient may be moved to a residential care facility.

Depending on the specific cognitive processes that are impaired, a patient with dementia may:

- behave inappropriately (for instance, tell unsuitable jokes or be overly familiar with strangers);

- misperceive reality (for instance, think that a caretaker is an intruder); or

- wander away while trying to get “home” (a place he or she lived previously).

Mild neurocognitive disorder A neurocognitive disorder characterized by a modest decline from baseline in at least one cognitive domain, but that decline is not enough to interfere with daily functioning.

According to DSM-5, the hallmark of mild neurocognitive disorder is evidence of a modest decline from baseline in at least one of the six cognitive domains above, but that decline is not enough to interfere with daily functioning (see TABLE 15.4). In contrast, the hallmark of major neurocognitive disorder is evidence of a substantial decline in at least one cognitive domain, and impaired daily functioning that results from this decline (see TABLE 15.5) (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Major neurocognitive disorder A neurocognitive disorder characterized by evidence of a substantial decline in at least one cognitive domain, and impaired daily functioning.

|

| Reprinted with permission from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, (Copyright ©2013). American Psychiatric Association. All Rights Reserved. |

|

| Reprinted with permission from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, (Copyright ©2013). American Psychiatric Association. All Rights Reserved. |

The diagnosis of mild neurocognitive disorder was introduced in DSM-5. The inclusion of this diagnosis has been criticized as pathologizing normal aging, especially because daily functioning should not be impaired for this diagnosis. As we discussed earlier, as people get older, some of their cognitive abilities modestly decline relative to their baseline—without any significant problems in their daily life (Frances, 2013; Greenberg, 2013).

CURRENT CONTROVERSY

Mild and Major Neurocognitive Disorders

Among the new diagnoses in DSM-5 is the diagnosis of mild neurocognitive disorder (see TABLE 15.6). This diagnosis is controversial because only a “modest” cognitive decline is needed (one or two standard deviations below what would be expected for a given patient)—and unlike almost any other diagnosis in DSM-5, the symptoms do not need to cause distress or impair functioning. In fact, a requirement for the diagnosis is that functioning is not impaired!

| Prevalence |

|

| Comorbidity |

|

| Onset |

|

| Course |

|

| Gender Differences |

|

| Cultural Differences |

|

| Source: Unless otherwise noted, the source for information is American Psychiatric Association, 2000, 2013. |

On the one hand, this new diagnosis can focus the attention of researchers and clinicians on early signs of dementia (Geda & Nedelska, 2012; Gutierrez et al., 1994). The new diagnosis will make it easier for researchers to investigate factors related to faster or slower decline, and clinicians may able to intervene earlier with new medications that delay or arrest further declines.

On the other hand, the new term can create confusion. The medical term for the level of cognitive ability that is in between normal functioning and dementia (or major neurocognitive disorder, in DSM-5 lingo) is mild cognitive impairment. This is the term neurologists use. So DSM-5 has created a different term, sowing confusion for mental health clinicians, patients, and their families. Patients will receive two diagnoses for the same condition (Siberski, 2013).

CRITICAL THINKING Given that neither distress nor impaired functioning are criteria, do you think mild neurocognitive disorder should be considered a “disorder”? Why or why not?

(James Foley, College of Wooster)

People whose cognitive functioning started out at a very high level may notice deficits in functioning that are mild symptoms of dementia, but neuropsychological testing is likely to show that the patient’s abilities are within the normal range for his or her age. The early signs of dementia might otherwise go undiagnosed if current abilities aren’t compared to previous abilities; with such early signs, the person might be diagnosed with mild neurocognitive disorder (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Harvey, 2005a).

Dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease

Alzheimer’s disease A medical condition in which the afflicted person initially has problems with both memory and executive function and which leads to progressive dementia.

The most common cause of dementia is Alzheimer’s disease (also called simply Alzheimer’s), in which the afflicted person initially has problems with both memory and executive function. As the disease advances, memory problems worsen, attention and language problems emerge, and spatial abilities may deteriorate; the patient may even develop psychotic symptoms, such as hallucinations and delusions (particularly persecutory delusions). In the final stage, the patient’s memory loss is complete—he or she doesn’t recognize family members and friends, can’t communicate, and is completely dependent on others for care. In Case 15.3, Diana Friel McGowin describes her experience with dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease; additional facts about dementia are provided in TABLE 15.6.

CASE 15.3 • FROM THE OUTSIDE: Dementia

Diana Friel McGowin was 45 years old when she became aware of memory problems. She got lost on the way home because no landmarks looked familiar; she was unable to remember her address or to recognize her cousin. After neuropsychological and neuroimaging tests, she was diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer’s disease (because the disorder emerged before age 65). In her memoir about the progressive nature of this disease, Living in the Labyrinth (1993), McGowin describes sharing with her neurologist some of the symptoms she was having:

I showed him the burns on my wrists and arms sustained because I forgot to protect myself when inserting or removing food from the oven. I told him of becoming lost in the neighborhood grocery store where I had shopped for over twenty years. I showed him my scribbled notes and sketched maps of how to travel to the bank, the post office, the grocery, and work. (p. 41)

She describes other memory problems as the disease progressed:

I sometimes lost my thread of thought in mid-sentence. Memories of childhood and long ago events were quite clear, yet I could not remember if I ate that day. On more than one occasion when my grandchildren were visiting, I forgot they were present and left them to their own devices. Moreover, on occasions when I had picked them up to come play at my house, the small children had to direct me home. (p–65)

Further into her memoir, she notes:

As my grip upon the present slips, more and more comfort is found within my memories of the past. Childhood nostalgia is so keen I can actually smell the aroma of the small town library where I spent so many childhood hours.

Painfully lonely, I still contrarily, deliberately, sit alone in my home. The radio and TV are silent. I am suspended. Somewhere there is that ever-present reminder list of what I am supposed to do today. But I cannot find it.

In the early phases of a progressive dementia, when the person has relatively little decline in executive function, he or she may become so depressed about the diagnosis and its prognosis that he or she attempts suicide. Diana McGowin became acutely aware of her symptoms during the early phase of the disease and worked hard to try to compensate by making maps and lists. With some patients, mental health clinicians may have difficulty determining whether the particular symptoms reflect delirium, dementia, or both (see TABLE 15.7).

| Unique to delirium | Unique to dementia | Common to both delirium and dementia |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Understanding Dementia

Dementia is caused by a variety of neurological factors, and according to DSM-5, each of these factors corresponds to the diagnosis of a specific mild or major neurocognitive disorder. In what follows we review the most common types of dementia: dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia, and dementias that result from other medical conditions.

Alzheimer’s Disease

Almost three quarters of dementia cases are caused by Alzheimer’s disease (Plassman et al., 2007); in DSM-5, this form of dementia is referred to as neurocognitive disorder due to Alzheimer’s disease. There is no routine lab test for diagnosing this disease at present, and so this type of dementia is diagnosed by ruling out other possible causes.

Courtesy of Galerie Beckel-Odille-Boicos, Paris

Courtesy of Galerie Beckel-Odille-Boicos, Paris

The Progression of Alzheimer’s Disease

The onset of Alzheimer’s disease is gradual, with symptoms becoming more severe over time. Often, the early signs of dementia of the Alzheimer’s type involve difficulty remembering recent events or newly learned information. In the early stages of Alzheimer’s, the memory problems are prominent (Petersen & O’Brien, 2006); it is only as the disease progresses that other sorts of deficits in cognitive processing emerge, such as aphasia, apraxia, agnosia, and deteriorated spatial abilities. (Such patients may often become lost when walking around their neighborhood.) Patients may also become irritable and their personality may change—and such changes may become more pronounced as cognitive functioning declines. In the final stage of the disease, perceptual-motor problems arise, creating difficulties with walking, talking, and self-care. Generally, these patients die about 8–10 years after the first symptoms emerge.

In some cases, people with dementia also have behavioral problems, such as those a woman reported about her husband:

My husband used to be such an easy-going, calm person. Now, he suddenly lashes out at me and uses awful language. Last week, he got angry when our daughter and her family came over and we sat down to eat. I never know when it’s going to happen. He’s changed so much—it scares me sometimes.

(National Institute on Aging, 2003, p. 47)

People with Alzheimer’s who behave in unusual or disturbed ways are more likely to have greater declines in cognitive functioning and to need institutional care sooner than patients whose behavior causes less concern (Scarmeas et al., 2007). As noted in TABLE 15.8, slightly more females than males develop this form of dementia, and it accounts for progressively more cases of dementia in older age groups.

| Age (in years) | Prevalence among males | Prevalence among females |

|---|---|---|

| 65 | 0.6% | 0.8% |

| 85 | 11% | 14% |

| 90 | 21% | 25% |

| 95 | 36% | 41% |

As people age beyond 65 years old, they are increasingly likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease. About half the cases in each age group have moderate to severe cognitive impairment (American Psychiatric Association, 2000).

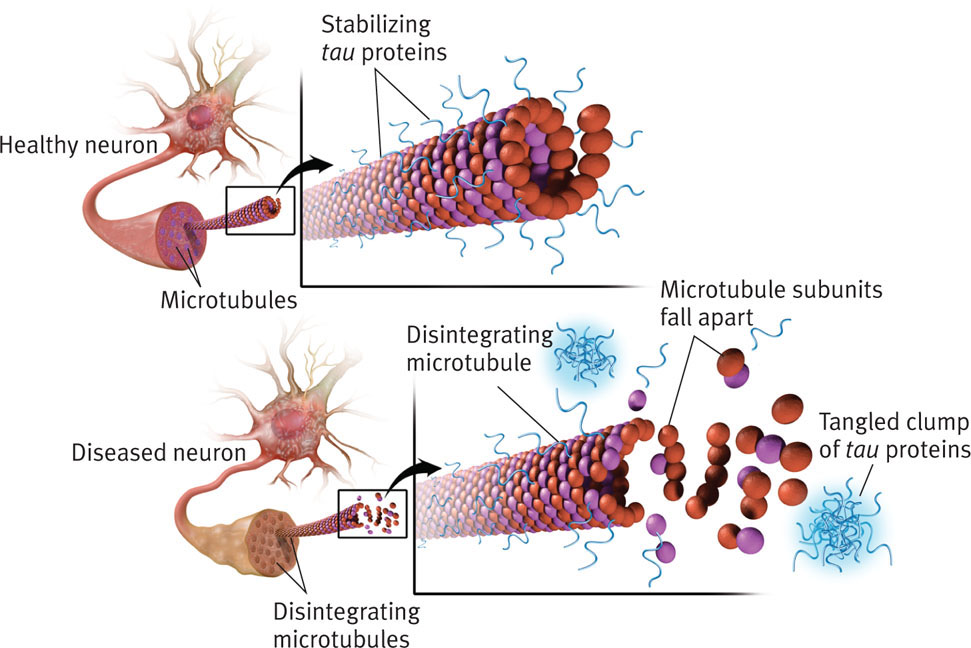

Brain Abnormalities Associated With Alzheimer’s Disease: Neurofibrillary Tangles and Amyloid Plaques

Two brain abnormalities are associated with Alzheimer’s disease: neurofibrillary tangles and amyloid plaques. The internal support structure of a neuron includes microtubules, which are tiny, hollow tubes that create tracks from the cell body to the end of the axon; nutrients are distributed within the cell via these microtubules. A protein, called tau, helps stabilize the structure of these tracks (see Figure 15.1). With Alzheimer’s disease, the tau proteins become twisted together into neurofibrillary tangles, and these proteins no longer hold together the microtubules—which thereby disrupts the neuron’s distribution system for nutrients. In addition, the collapse of this support structure prevents normal communication with other neurons. This process may also contribute to the death of neurons. In fact, people with Alzheimer’s have smaller brains than usual (Henneman et al., 2009).

Neurofibrillary tangles The mass created by tau proteins that become twisted together and destroy microtubules, leaving the neuron without a distribution system for nutrients.

Amyloid plaques Fragments of protein that accumulate on the outside surfaces of neurons, particularly neurons in the hippocampus.

The brains of people with Alzheimer’s disease are abnormal in another way—they have amyloid plaques, which are fragments of proteins (one type of which is called amyloid) that accumulate on the outer surfaces of neurons, particularly neurons in the hippocampus—the brain area predominately involved in storing new information in memory.

Researchers have not yet determined whether the neurofibrillary tangles and plaques cause Alzheimer’s disease or are a byproduct of some other process that causes the disease (National Institute on Aging, 2003; Schwitzer, 2012). However, neurofibrillary tangles and amyloid plaques are generally discovered during autopsies, and PET scanning that uses a particular chemical marker has been able to detect the amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles that distinguish Alzheimer’s disease from other causes of memory problems in living patients (Ikonomovic et al., 2008; Small et al., 2006; Snitz et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2012).

Genetics

People who have a specific version of one gene, apo E, are more susceptible to late-onset Alzheimer’s disease than people who don’t have this particular gene. However, someone can have this version of the apo E gene and not develop Alzheimer’s; conversely, someone can develop Alzheimer’s and not have this version of the gene.

In contrast, early-onset Alzheimer’s is caused by the mutation of one of three other genes, and two of these mutations lead to Alzheimer’s disease in 100% of cases. However, the third type of mutation (a rare form called presenilin 2) does not always cause the disease (Williamson-Catania, 2007), which suggests that other neurological factors and/or psychosocial factors may play a role.

Vascular Dementia

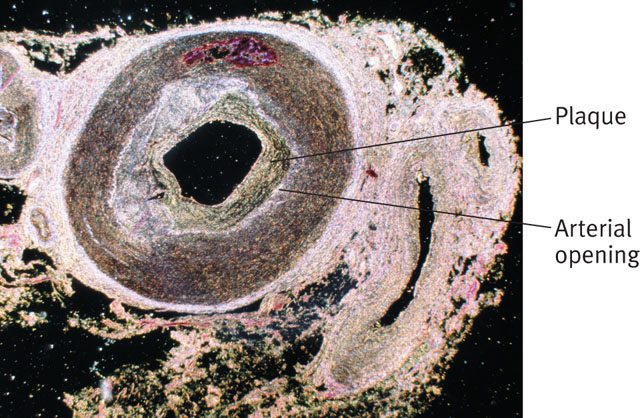

Vascular dementia A type of dementia caused by reduced or blocked blood supply to the brain, which arises from plaque buildup or blood clots.

Vascular refers to blood vessels, and vascular diseases refer to problems with blood vessels, such as high blood pressure or high cholesterol. Vascular disease can reduce or block blood supply to the brain, which in turn can cause vascular dementia (in DSM-5, referred to as vascular neurocognitive disorder). Blood vessels can be involved in dementia in two ways: (1) Plaque builds up on artery walls, making the arteries narrower, which then diminishes blood flow to the brain, or (2) bits of clotted blood block the inside of arteries, which then prevents blood from reaching the brain. Such clots can cause a series of small strokes (sometimes referred to as transient ischemic attacks or ministrokes), in which blood supply to parts of the brain is temporarily blocked, leading to transient impaired cognition or consciousness. When multiple ministrokes occur over time, dementia can arise as brain areas involved in cognitive functioning become impaired. This form of dementia can have a gradual onset. In contrast, a single, large stroke inflicts more brain damage than a series of ministrokes; in such cases, vascular dementia has an abrupt onset. Note that because dementia involves deficits in memory and aphasia, apraxia, agnosia, or problems with executive functions, not all strokes produce dementia: Some strokes only produce very specific problems, such as aphasia or deficits in executive functions, but the results of the stroke could still merit the diagnosis of a mild or major neurocognitive disorder.

Symptoms of vascular dementia can wax and wane over a given 24-hour period, but even the patient’s highest level of functioning is lower than it was before dementia set in (Puente, 2003). In addition, neuroimaging may reveal lesions (“dead” neurons) in particular brain areas. People with vascular dementia may also have Alzheimer’s disease, particularly if they are very old (Kalaria & Ballard, 1999). Vascular dementia is more common in men than women.

The course of vascular dementia is variable, depending on the specific brain areas affected; when symptoms become more severe, they worsen in a stepwise fashion, with more deficits apparent after each instance of reduced blood supply to the brain. Aggressive treatment of the underlying vascular disease (typically via medication) may prevent additional strokes or reduced blood flow to brain areas.

Dementia Due to Other Medical Conditions

Dementia can also be caused by a variety of other medical conditions, including Parkinson’s disease, late-stage HIV infection, and Huntington’s disease. With these and certain other medical conditions, the onset can be gradual or sudden, the course can range from acute to chronic, and the patient may also develop behavioral disturbances.

Dementia Due to Parkinson’s Disease

Parkinson’s disease is characterized by a slow, progressive loss of motor function; typical symptoms are trembling hands, a shuffling walk, and muscular rigidity. About 1 million Americans have Parkinson’s disease, and approximately 50% of people with Parkinson’s disease develop dementia due to this disease, in DSM-5 referred to as neurocognitive disorder due to Parkinson’s disease. People who develop this type of dementia are usually older (age of onset is about 65 years old) or are in a more advanced stage of the disease (Papapetropoulos et al., 2005). The dementia generally involves problems in memory and executive functions. Comorbid depression can cause additional cognitive deficits.

Parkinson’s disease causes damage to dopamine-releasing neurons in an area of the brain known as the substantia nigra. As a consequence, the brains of these patients do not have normal amounts of this neurotransmitter, which is critically involved in motor functions as well as executive functions. Parkinson’s disease is thought to arise from a combination of genetics and other neurological factors, such as brain damage caused by exposure to pesticides and other toxins.

Dementia Due to Lewy Bodies

Another type of progressive dementia is dementia due to Lewy bodies, in DSM-5 referred to as neurocognitive disorder with Lewy bodies. Lewy bodies consist of a type of protein that, in some people, builds up inside neurons that produce dopamine or acetylcholine and can eventually cause the neurons to die. The neurons most often affected are involved in memory and motor control. (Neurons associated with other functions can also be affected.)

Clinicians may have difficulty distinguishing this form of dementia from Alzheimer’s, and autopsies have revealed that about 20% of people who were diagnosed with Alzheimer’s also had abnormal Lewy bodies (Rabin et al., 2006). However, although people who have dementia due to Lewy bodies have characteristics in common with people who have Alzheimer’s, they have more severe disruptions of:

- visuospatial ability, and

- executive functions (Kaufer, 2002; Knopman et al., 2003; Walker & Stevens, 2002).

Moreover, people who have dementia due solely to Lewy bodies have three features that are not shared by people who have dementia that arises from Alzheimer’s disease:

- the presence of (visual) hallucinations early in the course of the disorder,

- a tendency to retain the ability to name objects, and

- stiff movements early in the course of the disorder, which are similar to that of people with Parkinson’s disease (rigid muscles, tremors, slowed movements, and a shuffling style of walking).

Like patients with Alzheimer’s disease, patients with dementia due to Lewy bodies progressively deteriorate until death, which on average occurs about 8–10 years after diagnosis.

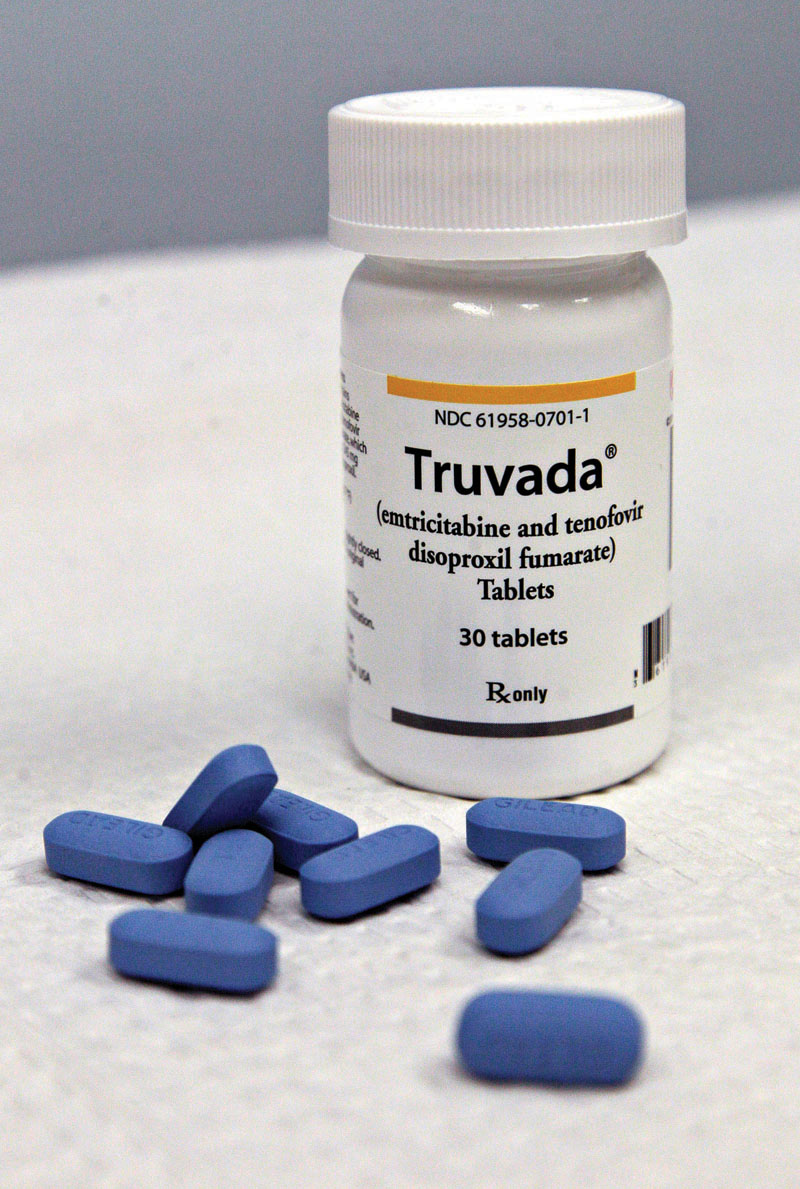

Dementia Due to HIV Infection

The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) can destroy white matter and subcortical brain areas, which then gives rise to a type of dementia referred to in DSM-5 as neurocognitive disorder due to HIV infection. The symptoms of this form of dementia include impaired memory, concentration, and problem solving, as well as cognitive slowing. Moreover, patients may exhibit signs of apathy, social withdrawal, delirium, delusions, or hallucinations. They may develop tremors or repetitive movements or have problems keeping their balance (McArthur et al., 2003; Price, 2003; Shor-Posner et al., 2000). Antiretroviral medications that treat HIV infection slow—and in some cases may actually reverse—the brain damage, improving cognitive functioning (Sacktor et al., 2006).

Dementia Due to Huntington’s Disease

Huntington’s disease A progressive disease that kills neurons and affects cognition, emotion, and motor functions; it leads to dementia and eventually results in death.

Huntington’s disease is a progressive disease that kills neurons and affects cognition, emotion, and motor functions; it leads to dementia and eventually results in death. Early symptoms of Huntington’s disease include bipolar-like mood swings between mania and depression, irritability, and hallucinations or delusions; in DSM-5 it is referred to as neurocognitive disorder due to Huntington’s disease. Motor symptoms include slow or restless movements, and the cognitive symptoms include memory problems (which become severe as the disease progresses), impaired executive function, and poor judgment.

Huntington’s disease is inherited and is based on a single gene. If a parent has Huntington’s disease, his or her children each have a 50% chance of developing it. Genetic testing can assess whether the gene is present.

Dementia Due to Head Trauma

Head trauma can cause dementia or other impaired cognitive functioning, referred to as neurocognitive disorder due to traumatic brain injury in DSM-5. The precise deficits and their severity depend on which brain areas are affected and to what degree. A person with this form of dementia may also behave unusually, such as being agitated. Such a patient may have amnesia for events during and after the trauma, as well as other persistent memory problems. In addition, he or she may have sensory or motor problems and even personality changes (becoming increasingly aggressive or apathetic or suffering severe mood swings) (American Psychiatric Association, 2000).

This form of dementia is most common among young males, who are more likely than others to engage in risk-taking behaviors (such as reckless drinking) that may lead to a single trauma to the head (such as a car accident); when the dementia is caused by multiple traumas (as occurs with boxers), it may become worse over time (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Substance/Medication-Induced Neurocognitive Disorder

When the cognitive deficits of dementia are caused by substance use but persist beyond the period of intoxication or withdrawal, the clinician makes the DSM-5 diagnosis of substance/medication-induced neurocognitive disorder. A patient who receives this diagnosis usually has a long history of substance use, and symptoms rarely occur in patients younger than 20 years. The onset is slow, as is the progression of deficits; the first symptoms arise while the person has a substance use disorder. If the person is over age 50, the deficits often are not reversible and may even get worse when the substance use is discontinued (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

As we’ve noted, dementia may be caused by a number of medical illnesses or conditions, and these causes are not mutually exclusive; a given person’s dementia may have more than one cause. For example, someone may have both vascular dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. When this occurs, the clinician diagnoses each type (cause) separately. TABLE 15.9 summarizes key facts about the different types of dementia.

| Dementia due to… | Approximate percentage of all dementia cases | Prognosis/course | Onset | Gender difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alzheimer’s disease | 70% | Poor | Gradual, often after age 65; early onset is rare | Slightly more common among women than men |

| Vascular disease | 15% (often comorbid with Alzheimer’s type) | Cognitive loss may remain stable or worsen in a stepwise fashion. | Abrupt; earlier age of onset than Alzheimer’s | More common among men |

| Lewy bodies | 15% (can be comorbid with Alzheimer’s type) | Poor | Gradual; age of onset is between 50 and 85 | Slightly more common among men than women |

| HIV infection | Less than 10% | Poor unless treated with antiretroviral medication | Gradual; depends on age at which HIV infection is acquired | Estimates of sex ratios vary, depending in part on the sex difference in HIV prevalence and the availability of antiretroviral treatment at the time a study is undertaken |

| Parkinson’s disease | Less than 10%; often comorbid with Alzheimer’s type and/or vascular dementia; about 50% of patients with Parkinson’s disease develop dementia | Poor | Gradual; typical age of onset is in the 70s | More men than women develop Parkinson’s disease, and so men are more likely to develop this type of dementia |

| Huntington’s disease | Less than 10% | Poor | Gradual; onset usually occurs in the 40s or 50s. | No sex difference |

| Head trauma | Unknown | Depends on the specific nature of the trauma | Usually abrupt, after the head injury | Unknown, but most common among young men |

| Substance-induced | Unknown | Variable, depends on the specific substance and deficits | Gradual; in the 30s and beyond | Unknown |

| Note: Most cases of dementia are caused by Alzheimer’s disease. However, dementia in a given person can arise from more than one cause, and the percentages in the second column reflect these comorbidities; for this reason, the numbers add up to more than 100%. | ||||

With a progressive dementia, such as occurs in Alzheimer’s disease, a person’s diagnosis may change over time from a mild neurocognitive disorder to major neurocognitive disorder; this changed diagnosis occurs after the disorder has advanced and the person’s cognitive abilities are impaired to the point where he or she can’t function effectively (e.g., can’t remember to pay bills or take medication). In other cases, such as cognitive impairments that arise from head trauma, a person’s deficits might remain relatively mild and stable, so that the person can functioning relatively well in daily life, with perhaps some reduced ability relative to his or her pervious baseline; in such cases, a mild neurocognitive disorder would not change to major neurocognitive disorder.

Treating Dementia

With most types of dementia, such as the Alzheimer’s type and vascular dementia, treatments cannot return cognitive functioning to normal (HIV-induced dementia being the exception to the rule, as noted earlier), and instead consist of rehabilitation. Given the high proportion of dementia that is caused by Alzheimer’s disease (see TABLE 15.9), in the following sections we focus on treatment for that type of dementia, unless otherwise noted.

Targeting Neurological Factors

Medications have been developed to delay the progression of cognitive difficulties in people with Alzheimer’s disease. One class of drugs, cholinesterase inhibitors, such as galantamine (Razadyne) or donepezil (Aricept), is used for mild to moderate cognitive symptoms; these medications increase levels of acetylcholine (Lyle et al., 2008; Poewe et al., 2006). Another type of drug, memantine (Namenda), affects levels of glutamate (Tariot et al., 2004) and is used to treat moderate to severe Alzheimer’s dementia (Kavirajan, 2009). Still other, experimental, medications are intravenous immunoglobulin (Relkin et al., 2012) and EVP-6124 (Hilts et al., 2012). Although each of these drugs may help some patients (Atri et al., 2008; Cummings et al., 2008; Homma et al., 2008), they are new, and few carefully controlled studies of these medications have been completed.

Antipsychotic medications are sometimes given for psychotic symptoms or behavioral disturbances, but the side effects of both traditional and atypical antipsychotics caution against their long-term use (Ballard & Howard, 2006; Schneider et al., 2006b). Patients with dementia due to Lewy bodies should not be given antipsychotic medication for behavioral disturbances because this type of medication makes their symptoms worse.

Targeting Psychological Factors

The American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry (2006) recommends that the first line of intervention for dementia should help patients maintain as high a quality of life as is possible, given the symptoms. Such interventions focus on psychological and social factors.

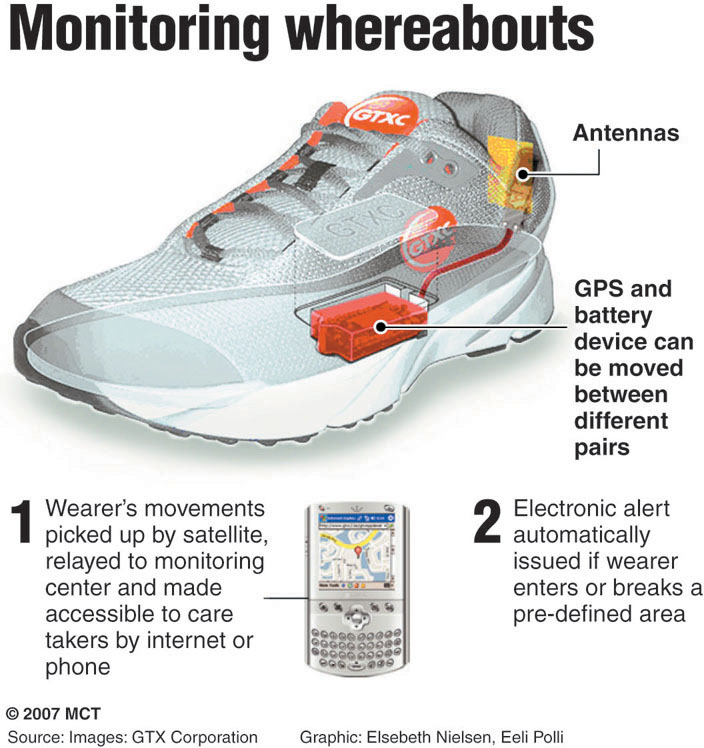

To target psychological factors, people in the early stages of dementia—and their friends and relatives—may be taught strategies and given devices to compensate for memory loss. Such strategies include ways of organizing information so that it can later be retrieved from memory more readily. One such strategy is the use of mnemonics, which may help people to remember simple information, such as where the car is parked at the mall. For example, someone might repeatedly visualize the location of the car in the parking lot, which will help him or her retain this information. In addition, structured and predictable daily activities can reduce patients’ confusion (Gitlin et al., 2010; Spector et al., 2000). Moreover, patients may be given a GPS tracking device to wear so that they can be found relatively quickly and easily if they get lost (Rabin et al., 2006).

People who are in the early stages of progressive dementias are often anxious and depressed (Porter et al., 2003; Ross et al., 1998). One type of treatment that may alleviate these comorbid conditions is reality orientation therapy (Giordano et al., 2010; Woods, 2004), which is designed to decrease a patient’s confusion by focusing on the here and now. For example, the clinician may frequently repeat the patient’s name (“Good morning, Mr. Rodrigues; how are you on this Monday morning, Mr. Rodrigues?”) and remind the patient of the day and time; calendars and clocks are located where the patient can see them easily. Patients whose cognitive functioning is impaired to the point where they are in residential centers are encouraged to join in activities rather than isolate themselves.

Another method that may decrease the depression and anxiety that can accompany progressive cognitive decline is reminiscence therapy, which stimulates the patients’ memories that are least affected by dementia—those of their early lives. When providing this treatment, the therapist focuses on patients’ life histories and asks patients to explore and share their experiences with group members or with the therapist; patients may feel relief at being able to remember some information, and their anxiety decreases and their mood improves (Subramaniam & Woods, 2012).

Caregivers—family members and paid caretakers—may be trained to treat behavioral disturbances, such as agitation and aggression that sometimes arise with dementia. Such training may lead them to first be asked to identify the antecedents and consequences of the problematic behavior (Ayalon et al., 2006; Spira & Edelstein, 2006). Following this, they are advised how to modify those aspects of the environment or personal interactions. For instance, if a patient becomes aggressive only at night after waking up to go to the bathroom, a night-light in his or her room may help reduce any anxiety that arises because the patient is confused upon awakening.

Targeting Social Factors

One way to reduce the cognitive load of someone with dementia is to enlist others to structure the patient’s environment so that memory is less important. For instance, family members can place labels on the outside of cupboards and room doors at home or at a residential facility; each label identifies what is on the other side of the door (for example, “dishes,” “kitchen,” “Sally Johnson’s room”). In some rehabilitation centers, the doors to bathrooms are painted a distinctive color, and arrows on the walls or floors show the direction to a bathroom, so patients don’t need to rely as much on memory to get around the facility (Wilson, 2004).

As cognitive and physical functioning decline, patients with dementia may receive services that target social factors—such as elder day care, which is a day treatment program for older adults with cognitive or physical impairments. Such day treatment both allows the patient to interact with other people and provides a respite for family members who care for the patient. As the patient continues to decline, however, he or she may require live-in caretakers or full-time care in a nursing home or other residential facility.

Taking care of a family member who has Alzheimer’s disease is often extremely stressful; for example, patients may need to be watched constantly and closely, for fear that they may inadvertently harm themselves or other people. This stress increases the caretaker’s risk of developing a psychological or medical disorder. In recent years, clinicians who treat patients with dementia have also reached out to family members who act as caretakers to provide education, support, and, when needed, treatment to help these people develop less stressful ways of interacting with the patients. Such interventions help family members (and, indirectly, the patients themselves) function as well as possible under the circumstances.

Thinking Like A Clinician

Sixty-five-year-old Lucinda recently retired from her job as corporate vice-president of marketing. Lucinda lives alone but frequently visits her son, his wife, and their young daughter. She’s noticed lately that she loses umbrellas and often forgets things—such as where her keys are, lunch dates with friends, and other appointments. She’s chalked up these problems to her retirement and the resulting changes in her daily routines. At what point might losing and forgetting things indicate a neurocognitive disorder? If you knew only that Lucinda had dementia, what should and shouldn’t you assume about its cause(s) and her prognosis?