Chapter Introduction

499

16

Reconstruction

1863–1877

Wartime Reconstruction

Presidential Reconstruction

Congressional Reconstruction

The Struggle in the South

Reconstruction Collapses

Conclusion: “A Revolution But Half Accomplished”

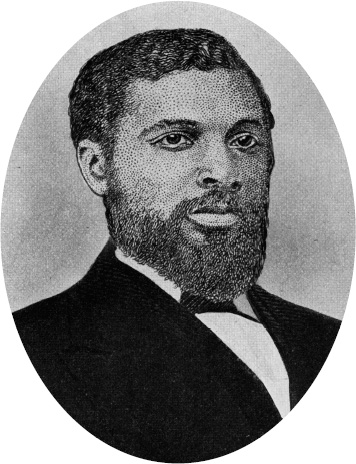

In 1856, John Rapier, a free black barber in Florence, Alabama, urged his four freeborn sons to flee the increasingly repressive and dangerous South. Searching for a color-blind society, the brothers scattered around the world. James T. Rapier chose Canada, where he went to live with his uncle in a largely black community and studied Greek and Latin in a log schoolhouse. After his conversion at a Methodist revival, James wrote to his father: “I have not thrown a card in 3 years[,] touched a woman in 2 years[,] smoked nor drunk any Liquor in going on 2 years.” He vowed, “I will endeavor to do my part in solving the problems [of African Americans] in my native land.”

The Union victory in the Civil War gave James Rapier the opportunity to redeem his pledge. In 1865, after more than eight years of exile, the twenty-seven-year-old Rapier returned to Alabama, where he presided over the first political gathering of former slaves in the state. Alabama freedmen produced a petition that called on the federal government to thoroughly reconstruct the South, to guarantee suffrage, free schools, and equal rights for all men, regardless of color.

Rapier soon discovered that Alabama’s whites found it agonizingly difficult to accept defeat and black freedom. They responded to the revolutionary changes under the banner “White Man — Right or Wrong — Still the White Man!” In 1868, when Rapier and other Alabama blacks vigorously supported the Republican presidential candidate, former Union general Ulysses S. Grant, the recently organized Ku Klux Klan went on a bloody rampage of whipping, burning, and shooting. A mob of 150 outraged whites scoured Rapier’s neighborhood seeking four black politicians they claimed were trying to “Africanize Alabama.” They caught and hanged three, but the “nigger carpetbagger from Canada” escaped. Rapier considered fleeing the state, but he decided to stay and fight.

By the early 1870s, Rapier had emerged as Alabama’s most prominent black leader. Demanding that the federal government end the violence against ex-slaves, guarantee their civil rights, and give them land, he won election in 1872 to the House of Representatives, where he joined six other black congressmen. Defeated for reelection in 1874 in a campaign marked by white violence and ballot-box stuffing, Rapier turned to cotton farming, generously giving thousands of dollars of his profits to black schools and churches.

But persistent black poverty and unrelenting racial violence convinced Rapier that blacks could never achieve equality and prosperity in the South. He purchased land in Kansas and urged Alabama’s blacks to escape with him. In 1883, however, before he could leave Alabama, Rapier died of tuberculosis at the age of forty-five.

500

In 1865, Union general Carl Schurz had foreseen many of the troubles Rapier would encounter in the postwar South. Schurz concluded that the Civil War was “a revolution but half accomplished.” Northern victory had freed the slaves, he observed, but it had not changed former slaveholders’ minds about blacks’ unfitness for freedom. Left to themselves, whites would “introduce some new system of forced labor, not perhaps exactly slavery in its old form but something similar to it.” To defend their freedom, Schurz concluded, blacks would need federal protection, land of their own, and voting rights. Until whites “cut loose from the past, it will be a dangerous experiment to put Southern society upon its own legs.”

As Schurz discovered, the end of the war did not mean peace. The United States was one of only two societies in the New World in which slavery ended in a bloody war. (The other was Haiti.) Not surprisingly, racial turmoil continued in the South after the armies quit fighting in 1865. The nation entered one of its most chaotic and conflicted eras — Reconstruction, a violent period that would define the defeated South’s status within the Union and the meaning of freedom for ex-slaves.

The place of the South within the nation and the extent of black freedom were determined not only in Washington, D.C., where the federal government played an active role, but also in the state legislatures and county seats of the South, where blacks eagerly participated in the process. Moreover, on farms and plantations from Virginia to Texas, ex-slaves struggled to become free workers while ex-slaveholders clung to the Old South. A small band of white women joined in the struggle for racial equality, and soon their crusade broadened to include gender equality. Their attempts to secure voting rights for women were thwarted, however.

Reconstruction witnessed a gigantic struggle to determine the consequences of Confederate defeat and emancipation. In the end, white Southerners prevailed. Their New South was a different South from the one to which most whites wished to return but also vastly unlike the one of which James Rapier dreamed.

501