1.3.3 Impeaching a President

Despite his defeats, Andrew Johnson had no intention of yielding control of reconstruction. In a dozen ways, he sabotaged Congress’s will and encouraged southern whites to resist. He issued a flood of pardons, waged war against the Freedmen’s Bureau, and replaced Union generals eager to enforce Congress’s Reconstruction Acts with conservative officers eager to defeat them. Johnson claimed that he was merely defending the “violated Constitution.” At bottom, however, the president subverted congressional reconstruction to protect southern whites from what he considered the horrors of “Negro domination.”

514

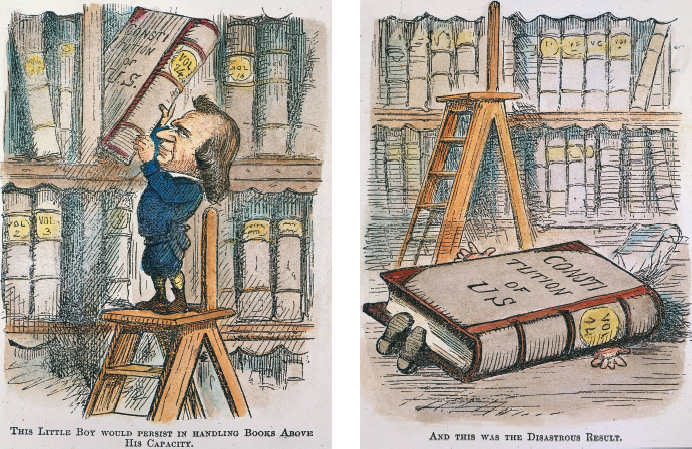

When Congress realized that overriding Johnson’s vetoes did not ensure that it got its way, it looked for other ways to exert its will. According to the Constitution, the House of Representatives can impeach and the Senate can try any federal official for “treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors.” Radicals argued that Johnson’s abuse of constitutional powers and his failure to fulfill constitutional obligations to enforce the law were impeachable offenses. But moderates interpreted the constitutional provision to mean violation of criminal statutes. As long as Johnson refrained from breaking the law, impeachment (the process of formal charges of wrongdoing against the president or other federal official) remained stalled.

Then, in August 1867, Johnson suspended Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton from office. The Tenure of Office Act, which had been passed earlier in the year, demanded the approval of the Senate for the removal of any government official who had been appointed with Senate approval. As required by the act, the president requested the Senate to consent to Stanton’s dismissal. When the Senate balked, Johnson removed Stanton anyway. “Is the President crazy, or only drunk?” asked a dumbfounded Republican moderate. “I’m afraid his doings will make us all favor impeachment.”

News of Johnson’s open defiance of the law convinced every Republican in the House to vote for a resolution impeaching the president. Supreme Court chief justice Salmon Chase presided over the Senate trial, which lasted from March until May 1868. Chase refused to allow Johnson’s opponents to raise broad issues of misuse of power and forced them to argue their case exclusively on the narrow legal grounds of Johnson’s removal of Stanton. Johnson’s lawyers argued that the president had not committed a criminal offense, that the Tenure of Office Act was unconstitutional, and that in any case it did not apply to Stanton, who had been appointed by Lincoln. When the critical vote came, thirty-five senators voted guilty and nineteen not guilty. The impeachment forces fell one vote short of the two-thirds needed to convict.

515

After his trial, Johnson called a truce, and for the remaining ten months of his term, congressional reconstruction proceeded unhindered by presidential interference. Without interference from Johnson, Congress revisited the suffrage issue.