1.1.1 “To Bind Up the Nation’s Wounds”

On March 4, 1865, in his second inaugural address, President Lincoln surveyed the history of the war and then looked ahead to peace. “With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right,” Lincoln said, “let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation’s wounds…to do all which may achieve and cherish a just, and a lasting peace.” Lincoln had contemplated reunion for nearly two years. While deep compassion for the enemy guided his thinking about peace, his plan for reconstruction aimed primarily at shortening the war and ending slavery.

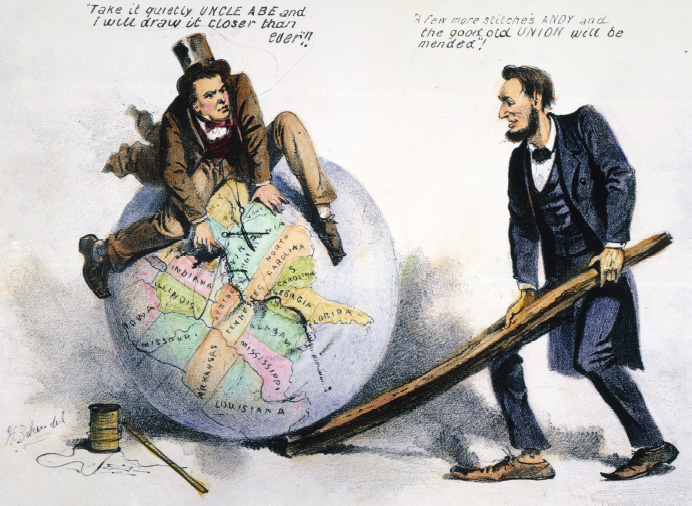

Lincoln’s Proclamation of Amnesty and Reconstruction in December 1863 set out his terms. He offered a full pardon, restoring property (except slaves) and political rights, to rebels willing to renounce secession and to accept emancipation. His offer excluded only high-ranking Confederate military and political officers and a few other groups. When 10 percent of a state’s voting population had taken an oath of allegiance, the state could organize a new government and be readmitted into the Union. Lincoln’s plan did not require ex-rebels to extend social or political rights to ex-slaves, nor did it anticipate a program of long-term federal assistance to freedmen. Clearly, the president looked forward to the rapid, forgiving restoration of the broken Union.

Lincoln’s easy terms enraged abolitionists such as Wendell Phillips of Boston, who charged that the president “makes the negro’s freedom a mere sham.” He “is willing that the negro should be free but seeks nothing else for him.” He compared Lincoln to the most passive of the Civil War generals: “What McClellan was on the battlefield — ‘Do as little hurt as possible!’ — Lincoln is in civil affairs — ‘Make as little change as possible!’” Phillips and other northern radicals called instead for a thorough overhaul of southern society. Their ideas proved to be too drastic for most Republicans during the war years, but Congress agreed that Lincoln’s plan was inadequate.

In July 1864, Congress put forward a plan of its own. Congressman Henry Winter Davis of Maryland and Senator Benjamin Wade of Ohio jointly sponsored a bill that demanded that at least half of the voters in a conquered rebel state take the oath of allegiance before reconstruction could begin. The Wade-Davis bill also banned all ex-Confederates from participating in the drafting of new state constitutions. Finally, the bill guaranteed the equality of freedmen before the law. Congress’s reconstruction would be neither as quick nor as forgiving as Lincoln’s. When Lincoln refused to sign the bill and let it die, Wade and Davis charged the president with usurpation of power. They warned Lincoln to confine himself to “his executive duties — to obey and execute, not make the laws — to suppress by arms armed rebellion, and leave political organization to Congress.”

Undeterred, Lincoln continued to nurture the formation of loyal state governments under his own plan. Four states — Louisiana, Arkansas, Tennessee, and Virginia — fulfilled the president’s requirements, but Congress refused to seat representatives from the “Lincoln states.” In his last public address in April 1865, Lincoln defended his plan but for the first time expressed publicly his endorsement of suffrage for southern blacks, at least “the very intelligent, and…those who serve our cause as soldiers.” The announcement demonstrated that Lincoln’s thinking about reconstruction was still evolving. Four days later, he was dead.

502