1.1.3 The African American Quest for Autonomy

Ex-slaves never had any doubt about what they wanted from freedom. They had only to contemplate what they had been denied as slaves. (See “Documenting the American Promise.”) Slaves had to remain on their plantations; freedom allowed blacks to see what was on the other side of the hill. Slaves had to be at work in the fields by dawn; freedom permitted blacks to sleep through a sunrise. Freedmen also tested the etiquette of racial subordination. “Lizzie’s maid passed me today when I was coming from church without speaking to me,” huffed one plantation mistress.

To whites, emancipation looked like pure anarchy. Blacks, they said, had reverted to their natural condition: lazy, irresponsible, and wild. Without the discipline of slavery, whites predicted, blacks would go the way of “the Indian and the buffalo.” Actually, former slaves were experimenting with freedom, but they could not long afford to roam the countryside, neglect work, and casually provoke whites. Soon, most were back at work in whites’ kitchens and fields.

But other items on ex-slaves’ agenda of freedom endured. They continued to dream of land and economic independence. “The way we can best take care of ourselves is to have land,” one former slave declared in 1865, “and turn it and till it by our own labor.” Freedmen also wanted to learn to read and write. Many black soldiers had become literate in the Union army, and they understood the value of the pen and book. “I wishes the Childern all in School,” one black veteran asserted. “It is beter for them then to be their Surveing a mistes [mistress].”

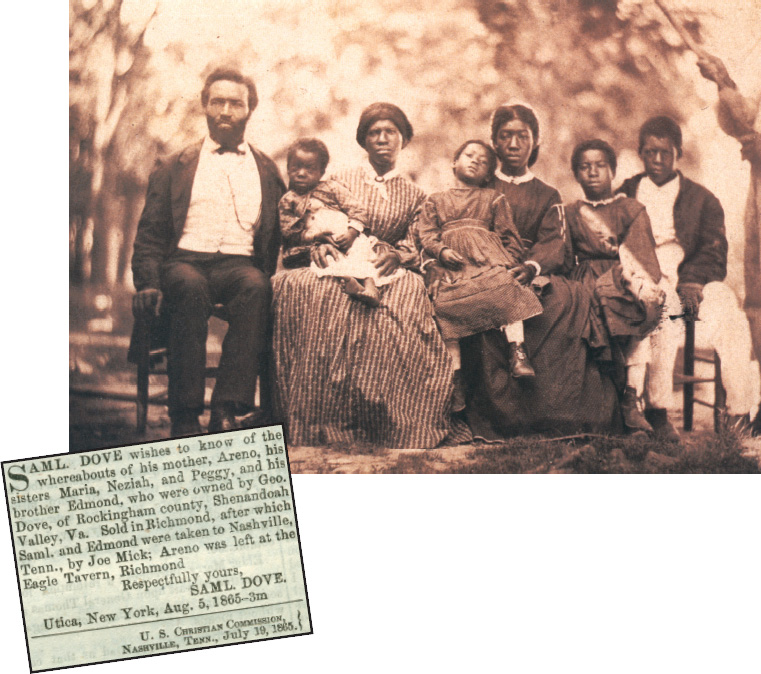

The restoration of broken families was another persistent black aspiration. Thousands of freedmen took to the roads in 1865 to look for kin who had been sold away or to free those who were being held illegally as slaves. A black soldier from Missouri wrote his daughters that he was coming for them. “I will have you if it cost me my life,” he declared. “Your Miss Kitty said that I tried to steal you,” he told them. “But I’ll let her know that god never intended for a man to steal his own flesh and blood.” And he swore that “if she meets me with ten thousand soldiers, she [will] meet her enemy.”

Independent worship was another continuing aspiration. African Americans greeted freedom with a mass exodus from white churches, where they had been required to worship when slaves. Some joined the newly established southern branches of all-black northern churches, such as the African Methodist Episcopal Church. Others formed black versions of the major southern denominations, Baptists and Methodists. Freedmen interpreted the events of the Civil War and reconstruction as Christian people. One black woman thanked Lincoln for the Emancipation Proclamation, declaring, “When you are dead and in Heaven, in a thousand years that action of yours will make the Angels sing your praises I know it.”

506

REVIEW

Why did Congress object to Lincoln’s wartime plan for reconstruction?