The American Promise: Printed Page 265

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 244

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 276

Tecumseh and Tippecanoe

The American Promise: Printed Page 265

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 244

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 276

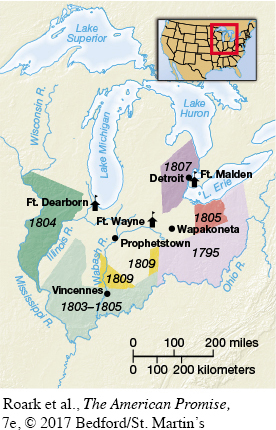

Page 265While the Madisons cemented alliances at home, difficulties with Britain and France overseas and with Indians in the old Northwest continued to increase. The Shawnee chief Tecumseh (see introduction to Chapter 10) actively solidified his confederacy, while the more northern tribes renewed their ties with supportive British agents in Canada, a potential source of food and weapons. If the United States went to war with Britain, serious repercussions on the frontier would clearly follow.

Shifting demographics put the Indians under pressure. The 1810 census counted some 230,000 Americans in Ohio, while another 40,000 inhabited the territories of Indiana, Illinois, and Michigan. The Indian population of the same area was much smaller, probably about 70,000.

Up to 1805, Indiana’s territorial governor, William Henry Harrison, had negotiated a series of treaties in a divide-

The American Promise: Printed Page 265

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 244

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 276

Page 266When he returned, Tecumseh was furious with both Harrison and the tribal leaders. Leaving his brother in charge at Prophetstown on the Tippecanoe River, the Shawnee chief left to seek alliances with tribes in the South. In November 1811, Harrison decided to attack Prophetstown with a thousand men. The two-

The Indian conflicts in the old Northwest soon merged into the wider conflict with Britain, now known as the War of 1812. Between 1809 and 1812, Madison teetered between declaring either Britain or France America’s primary enemy, as attacks by both countries on U.S. ships continued. In 1809, Congress replaced Jefferson’s embargo with the Non-

The new Congress seated in March 1811 contained several dozen young Republicans from the West and South who would come to be known as the War Hawks. Led by thirty-

In June 1812, Congress declared war on Great Britain in a vote divided along sectional lines: New England and some Middle Atlantic states opposed the war, fearing its effect on commerce, while the South and West strongly favored it. Ironically, Britain had just announced that it would stop the search and seizure of American ships, but the war momentum would not be slowed. The Foreign Relations Committee issued an elaborate justification titled Report on the Causes and Reasons for War, written mainly by Calhoun and containing extravagant language about Britain’s “lust of power,” “unbounded. . . tyranny,” and “mad ambition.” These were fighting words in a war that was in large measure about insult and honor. (See “Analyzing Historical Evidence: The Nation’s First Formal Declaration of War.”)

The War Hawks proposed an invasion of Canada, confidently predicting victory in four weeks. Instead, the war lasted two and a half years, and Canada never fell. The northern invasion turned out to be a series of blunders that revealed America’s grave unpreparedness for war against the unexpectedly powerful British and Indian forces (Map 10.3). By the fall of 1812, the outlook was grim.

Worse, the New England states were slow to raise troops, and some New England merchants carried on illegal trade with Britain. The fall presidential election pitted Madison against DeWitt Clinton of New York, nominally a Republican but able to attract the Federalist vote. Clinton picked up electoral votes from all of New England, with the exception of Vermont, and from New York, New Jersey, and part of Maryland. Madison won in the electoral college, 128 to 89, but his margin of victory was considerably smaller than in 1808.

In late 1812 and early 1813, the tide began to turn in the Americans’ favor. First came some victories at sea. Then the Americans attacked York (now Toronto) and burned it in April 1813. A few months later, Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry defeated the British fleet at the western end of Lake Erie. Emboldened, General Harrison drove an army into Canada from Detroit and in October 1813 defeated the British and Indians at the battle of the Thames, where Tecumseh was killed.

Creek Indians in the South who had allied with Tecumseh’s confederacy were also plunged into war. Some 10,000 living in the Mississippi Territory put up a spirited fight against U.S. forces for ten months. But the Creek War ended suddenly in March 1814 when a general named Andrew Jackson led 2,500 Tennessee militiamen in a bloody attack called the Battle of Horseshoe Bend. More than 550 Indians were killed, and several hundred more died trying to escape across a river. Later that year, General Jackson extracted from the defeated tribe a treaty relinquishing thousands of square miles of their land to the United States.