The American Promise: Printed Page 271

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 249

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 284

Chapter Chronology

Women and Church Governance

In most Protestant denominations around 1800, white women made up the majority of congregants. Yet church leadership of most denominations rested in men’s hands. There were some exceptions, however. In Baptist congregations in New England, women served along with men on church governance committees, deciding on the admission of new members, voting on hiring ministers, and even debating doctrinal points. Quakers, too, had a history of recognizing women’s spiritual talents. Some were accorded the status of minister, capable of leading and speaking in Quaker meetings.

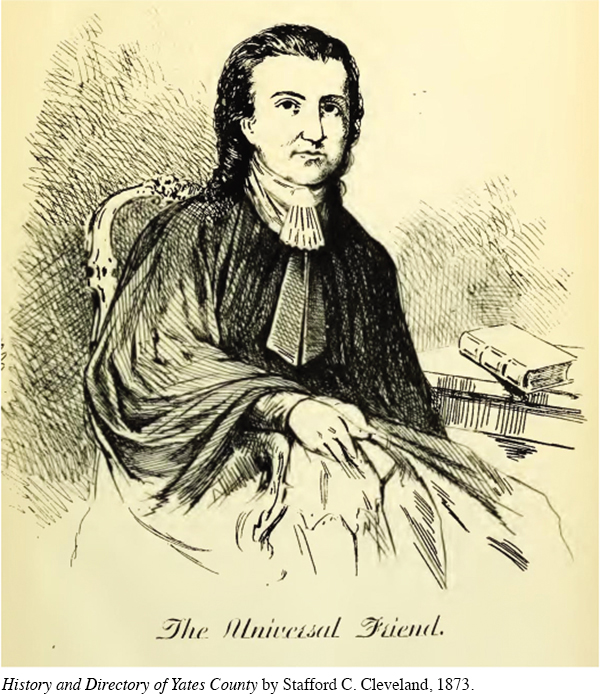

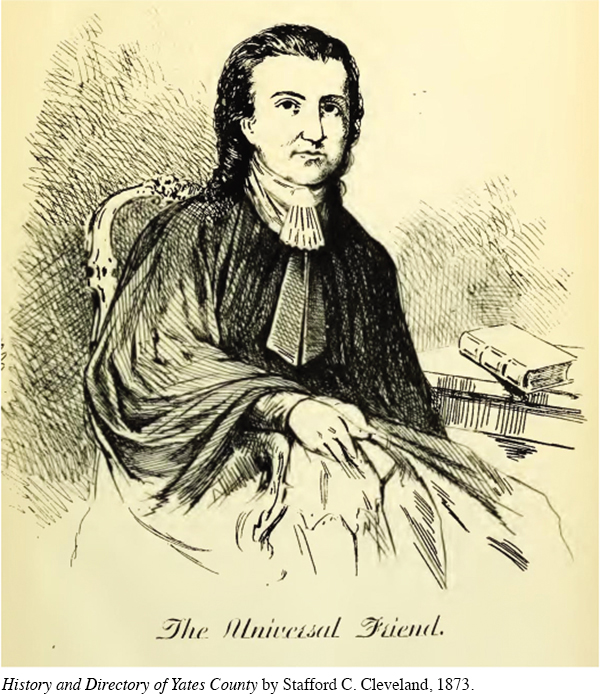

VISUAL ACTIVITYWomen and the Church: Jemima Wilkinson In this engraving, Jemima Wilkinson, “the Publick Universal Friend,” wears a clerical collar and body-obscuring robe, much as a male minister would wear, in keeping with the claim that the former Jemima was now a person without gender. Wilkinson’s hair is swept back from the forehead and curled at the neck in the style of men’s powdered wigs of the 1790s.READING THE IMAGE: Was Wilkinson merely masculinized by dress and deportment, or did the “Universal Friend” truly transcend gender?CONNECTIONS: Why was it so difficult for women to attain religious authority in the early Republic? What allowed a few to rise above social limitations?

History and Directory of Yates County by Stafford C. Cleveland, 1873.

Between 1790 and 1820, a small and highly unusual set of women actively engaged in open preaching. Most were from Freewill Baptist groups centered in New England and upstate New York. Others came from small Methodist sects, and yet others rejected any formal religious affiliation. Probably fewer than a hundred such women existed, but several dozen traveled beyond their local communities, creating converts and controversy. They spoke from the heart, without prepared speeches, often exhibiting trances and claiming to exhort (counsel or warn) rather than to preach.

The best-known exhorting woman was Jemima Wilkinson, who called herself “the Publick Universal Friend.” After a near-death experience from a high fever, Wilkinson proclaimed her body no longer female or male but the incarnation of the “Spirit of Light.” She dressed in men’s clothes, wore her hair in a masculine style, shunned gender-specific pronouns, and preached openly in Rhode Island and Philadelphia. In the early nineteenth century, Wilkinson established a town called New Jerusalem in western New York with some 250 followers. Her fame was sustained by periodic newspaper articles that fed public curiosity about her lifelong cross-dressing and her unfeminine forcefulness.

The decades from 1790 to the 1820s marked a period of unusual confusion, ferment, and creativity in American religion. New denominations blossomed, new styles of religiosity gripped adherents, and an extensive periodical press devoted to religion popularized all manner of theological and institutional innovations. In such a climate, the age-old tradition of gender subordination came into question here and there among the most radically democratic of the churches. But the presumption of male authority over women was deeply entrenched in American culture. Even denominations that had allowed women to participate in church governance began to pull back, and most churches reinstated patterns of hierarchy along gender lines.