The American Promise: Printed Page 278

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 256

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 291

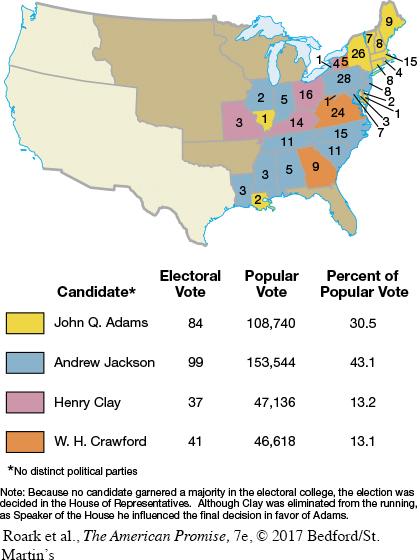

The Election of 1824

Monroe’s nonpartisan administration was the last of its kind, a throwback to eighteenth-

Crucially helping them to maneuver were their wives, who accomplished some of the work of modern campaign managers by courting men—

John Quincy Adams (and Louisa Catherine) was ambitious for the presidency, but so were others. Candidate Henry Clay, Speaker of the House and negotiator of the Treaty of Ghent with Britain in 1814, promoted a new “American System,” a package of protective tariffs to encourage manufacturing and federal expenditures for internal improvements such as roads and canals. Treasurer William Crawford was a favorite of Republicans from Virginia and New York, even after he suffered an incapacitating stroke in mid-

The American Promise: Printed Page 278

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 256

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 291

Page 279The final candidate was an outsider and a latecomer: General Andrew Jackson of Tennessee. Jackson had far less national political experience than the others, but he enjoyed great celebrity from his military career. In 1824, on the anniversary of the battle of New Orleans, the Adamses threw a spectacular ball in his honor, hoping that some of Jackson’s charisma would rub off on Adams, who was not yet thinking of Jackson as a rival for office. Not long after, Jackson’s supporters put his name forward for the presidency, and voters in the West and South reacted with enthusiasm; Adams was dismayed, and Calhoun dropped out of the race and shifted his attention to winning the vice presidency.

Along with democratizing the vote, eighteen states (out of the full twenty-

In the electoral college, Jackson received 99 votes, Adams 84, Crawford 41, and Clay 37 (Map 10.5). Jackson lacked a majority, so the House of Representatives stepped in for the second time in U.S. history. Each congressional delegation had one vote; according to the Constitution’s Twelfth Amendment, passed in 1804, only the top three candidates joined the runoff. Thus Henry Clay was out of the race and in a position to bestow his support on another candidate.

The American Promise: Printed Page 278

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 256

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 291

Page 280Jackson’s supporters later characterized the election of 1824 as the “corrupt bargain.” Clay backed Adams, and Adams won by one vote in the House in February 1825. Clay’s support made sense on several levels. Despite strong mutual dislike, he and Adams agreed on issues such as federal support to build roads and canals. Moreover, Clay was uneasy with Jackson’s volatile temperament and unstated political views and with Crawford’s diminished capacity. What made Clay’s decision look “corrupt” was that immediately after the election, Adams offered to appoint Clay secretary of state—

In fact, there probably was no concrete bargain; Adams’s subsequent cabinet appointments demonstrated his lack of political astuteness. But Andrew Jackson felt that the election had been stolen from him, and he wrote bitterly that “the Judas of the West [Clay] has closed the contract and will receive the thirty pieces of silver.”