The American Promise: Printed Page 347

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 318

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 362

Introduction to Chapter 13

The American Promise: Printed Page 347

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 318

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 362

Page 34713

The Slave South

1820–

CONTENT LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading and studying this chapter, you should be able to:

Identify the ways slavery, a plantation-

based economy, and biracialism distinguished the antebellum South from the North. Explain how a plantation was physically organized, and describe the roles of the plantation master and mistress. Define the ideology of paternalism and its role on the plantation.

Describe the lives led by slaves in the Old South and the elements that contributed to a semi-

autonomous slave culture. Explain why free blacks posed an ideological dilemma for white Southerners and why their freedom was precarious.

Identify the “plain folk” of the Old South.

Explain both how the South became increasingly democratic during the second quarter of the nineteenth century and how planters managed to retain their power.

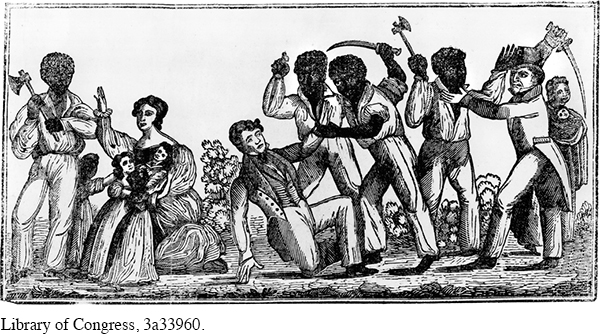

NAT TURNER WAS BORN A SLAVE IN SOUTHAMPTON COUNTY, VIRGINIA, in October 1800. His parents noticed special marks on his body, which they said were signs that he was “intended for some great purpose.” His master said that he learned to read without being taught. As an adolescent, he adopted an austere lifestyle of Christian devotion and fasting. In his twenties, he received visits from the “Spirit,” the same spirit, he believed, that had spoken to the ancient prophets. In time, Nat Turner began to interpret these things to mean that God had appointed him an instrument of divine vengeance for the sin of slaveholding.

On the morning of August 22, 1831, he set out with six friends—

The American Promise: Printed Page 347

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 318

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 362

Page 348White Virginians blamed the rebellion on outside agitators. In 1829, David Walker, a freeborn black man living in Boston, had published his An Appeal . . . to the Coloured Citizens of the World, an invitation to slaves to rise up in bloody revolution, and copies had fallen into the hands of Virginia slaves. Moreover, on January 1, 1831, the Massachusetts abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison had published the first issue of the Liberator, his fiery newspaper (see “Organizing against Slavery” in chapter 11).

In the months following the insurrection, the Virginia legislature reaffirmed the state’s determination to preserve slavery by passing laws that strengthened the institution and further restricted free blacks. A professor at the College of William and Mary, Thomas R. Dew, published a vigorous defense of slavery that became the bible of Southerners’ proslavery arguments. More than ever, the nation was divided along the Mason-

Black slavery increasingly molded the South into a distinctive region. In the decades after 1820, Southerners, like Northerners, raced westward; but unlike Northerners who spread small farms, manufacturing, and free labor, Southerners spread slavery, cotton, and plantations. Geographic expansion meant that slavery became more vigorous and more profitable than ever, embraced more people, and increased the South’s political power. Antebellum Southerners sometimes found themselves at odds with one another—

CHRONOLOGY

| 1808 |

|

| 1810s– |

|

| 1820s– |

|

| 1822 |

|

| 1829 |

|

| 1830 |

|

| 1831 |

|

| 1836 |

|

| 1840 |

|

| 1845 |

|

| 1860 |

|