The American Promise: Printed Page 363

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 330

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 377

Work

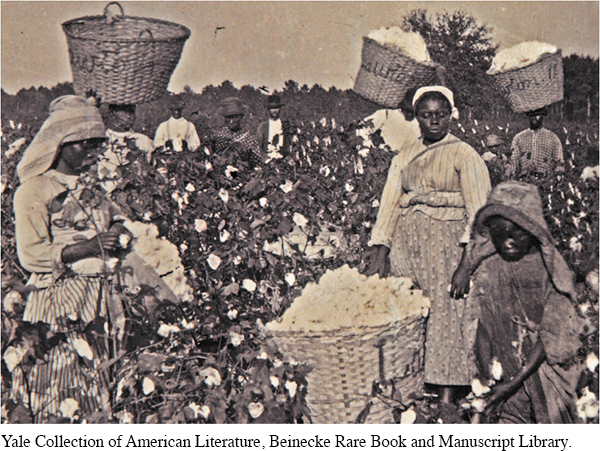

Whites enslaved blacks for their labor, and all slaves who were capable of productive labor worked. Former slave Carrie Hudson recalled that children who were “knee high to a duck” were sent to the fields to carry water to thirsty workers or to protect ripening crops from hungry birds. Others helped in the slave nursery, caring for children even younger than themselves, or in the big house, where they swept floors or shooed flies in the dining room. When slave boys and girls reached the age of eleven or twelve, masters sent most of them to the fields. After a lifetime of labor, old women left the fields to care for the small children and spin yarn, and old men moved on to mind livestock and clean stables.

The overwhelming majority of plantation slaves worked as field hands. Planters sometimes assigned men and women to separate gangs, the women working at lighter tasks and the men doing the heavy work of clearing and breaking the land. But women also did heavy work. “I had to work hard,” Nancy Boudry remembered, and “plow and go and split wood just like a man.” The backbreaking labor and the monotonous routines caused one ex-

A few slaves (about one in ten) became house servants. Nearly all of those (nine out of ten) were women. They cooked, cleaned, babysat, washed clothes, and did the dozens of other tasks the master and mistress required. House servants were constantly on call, with no time that was entirely their own. Since no servant could please constantly, most bore the brunt of white frustration and rage. Ex-

Even rarer than house servants were skilled artisans. In the cotton South, no more than one slave in twenty (almost all men) worked in a skilled trade. Most were blacksmiths and carpenters, but slaves also worked as masons, mechanics, millers, ginsmiths, and shoemakers. Skilled slave fathers took pride in teaching their crafts to their sons. “My pappy was one of the black smiths and worked in the shop,” John Mathews remembered. “I had to help my pappy in the shop when I was a child and I learnt how to beat out the iron and make wagon tires, and make plows.”

The American Promise: Printed Page 363

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 330

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 377

Page 364Rarest of all slave occupations was that of slave driver. Probably no more than one male slave in a hundred worked in this capacity. These men were well named, for their primary task was driving other slaves to work harder in the fields. In some drivers’ hands, the whip never rested. Ex-

Normally, slaves worked from what they called “can to can’t,” from “can see” in the morning to “can’t see” at night. Even with a break at noon for a meal and rest, it made for a long day. For slaves, Lewis Young recalled, “work, work, work, ’twas all they do.”