The American Promise: Printed Page 375

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 344

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 392

Introduction to Chapter 14

The American Promise: Printed Page 375

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 344

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 392

Page 37514

The House Divided

1846–

CONTENT LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading and studying this chapter, you should be able to:

Explain why the question of extending slavery to federal territories was the focus of constitutional debate from 1846 to 1860. Define the Wilmot Proviso, including who supported and opposed it, and why.

Relate how the debate over the expansion of slavery affected the election of 1848. Explain what led to the Compromise of 1850.

Determine what destroyed the second American party system in the 1850s, and how the electorate realigned.

Describe how Kansas was settled and organized, and how it got the name “Bleeding Kansas.” Explain the Dred Scott decision and how it shaped the perceptions of the North.

Explain the political rise of Abraham Lincoln.

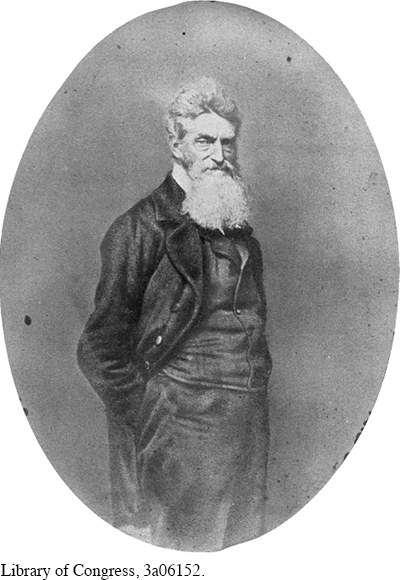

GRIZZLED, GNARLED, AND FIFTY-

After the killings, Brown slipped out of Kansas and reemerged in the East, where for thirty months he begged money to support his vague plan for military operations against slavery. On the night of October 16, 1859, Brown took his war against slavery into the South. With only twenty-

The American Promise: Printed Page 375

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 344

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 392

Page 376Months before the raid, Brown had claimed, “When I strike, the bees will begin to swarm.” Brown said he would arm slaves and they would then fight a war of liberation. Brown, however, neglected to inform the slaves when he had arrived in Harpers Ferry, and the few who knew of his arrival wanted nothing to do with his enterprise. “It was not a slave insurrection,” Abraham Lincoln observed. “It was an attempt by white men to get up a revolt among slaves, in which the slaves refused to participate. In fact, it was so absurd that the slaves, with all their ignorance, saw plainly enough it could not succeed.”

White Southerners viewed Brown’s raid as proof that Northerners actively sought to incite slaves in bloody rebellion. Sectional tension was as old as the Constitution, but hostility had escalated with the outbreak of war with Mexico in May 1846 (see “The Mexican-American War, 1846–1848” in chapter 12). Only three months after the war began, national expansion and the slavery issue intersected when Representative David Wilmot introduced a bill to prohibit slavery in any territory that might be acquired as a result of the war. After that, the problem of slavery in the territories became the principal wedge that divided the nation.

“Mexico is to us the forbidden fruit,” South Carolina senator John C. Calhoun declared at the war’s outset. “The penalty of eating it [is] to subject our institutions to political death.” For a decade and a half, the slavery issue intertwined with the fate of former Mexican land, poisoning the national political debate. Slavery proved powerful enough to transform party politics into sectional politics. Rather than Whigs and Democrats confronting one another across party lines, Northerners and Southerners eyed one another hostilely across the Mason-

CHRONOLOGY

| 1820 |

|

| 1846 |

|

| 1847 |

|

| 1848 |

|

| 1849 |

|

| 1850 |

|

| 1852 |

|

| 1853 |

|

| 1854 |

|

| 1856 |

|

| 1857 |

|

| 1858 |

|

| 1859 |

|

| 1860 |

|

| 1861 |

|