The American Promise: Printed Page 384

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 402

MAKING HISTORICAL ARGUMENTS

The American Promise: Printed Page 384

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 402

Page 384Filibusters: Were They the Underside of Manifest Destiny?

Each year, the citizens of Caborca, a small town in the northern state of Sonora, Mexico, celebrate the defeat there in 1857 of a private American army, the “Arizona Colonization Company,” under the command of Henry A. Crabb. When the governor of Sonora faced an insurrection, he invited Crabb, a Mississippian who had followed the gold rush to California, to help him repress his enemies in exchange for mining rights and land. Crabb marched his band of sixty-

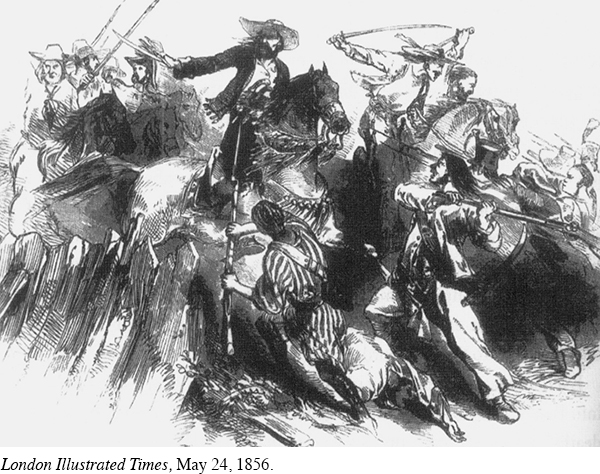

Henry Crabb was one of thousands of American adventurers, known as “filibusters” (from the Spanish filibustero, meaning “freebooter” or “pirate”), who in the mid-

The Americans who joined rampaging invading armies shared many traits and beliefs with Americans who propelled westward expansion. Filibusters felt proud to be American, were sure of their own racial and national superiority, and tended toward violence. Like the California gold rush, filibustering promised economic opportunity; recruiters promised land, good pay, bonuses, and other rich rewards. Young men saw participation as an exhilarating adventure, a chance to travel to exotic lands, face unknown dangers, and validate their manhood. “Glory or the grave,” one participant declared. What is more, filibusters were convinced that their work expanded American freedom. They had no respect for Hispanic peoples and anticipated their redemption through “Anglo-

Revealingly, John L. O’Sullivan, a radical champion of manifest destiny, also belligerently championed the filibusters. After eagerly endorsing the annexation of Mexican land, he turned his attention to Cuba. O’Sullivan looked forward to ridding Cuba of Spanish colonial rule and expanding American ideals. He vigorously denounced critics of American expansionism as “imbeciles” and “vile toads.” While O’Sullivan himself wanted no part in spreading slavery, many who were interested in Cuba served the interests of land-

During the 1850s, filibustering became primarily a southern crusade. One of the most vigorous filibusters to appeal to southern interests was Narciso López, a Venezuelan-

The most successful of all proslavery filibusters was William Walker of Tennessee. In May 1855, Walker and an army of fifty-

By the time filibustering lost steam in the late 1850s, Americans held mixed opinions of filibusters. Some condemned them as criminals and cutthroats, while others celebrated them as heroes, cut from the same cloth as hardy western pioneers. Defenders claimed that Latin American peoples stood in the way of progress and civilization just as much as Indians did. One historian concluded that filibusters were “criminals from manifest destiny’s underworld” and another “chapter in the history of American expansionism.” A leading proslavery ideologue, George Fitzhugh, defended filibustering through historical comparison: “They who condemn the modern filibuster . . . must also condemn the discoverers and settlers of America, of the East Indies of Holland, and of the Indian and Pacific Oceans.”

Questions for Analysis

Summarize the Argument: What is the argument for filibustering as an expression of manifest destiny?

Analyze the Evidence: What specific evidence supports the argument that filibustering was an expression of manifest destiny? Is the evidence persuasive?

Consider the Context: What did filibusters share with pioneers heading west under the banner of manifest destiny? Were there any important differences?