The American Promise: Printed Page 387

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 356

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 405

The New Parties: Know-Nothings and Republicans

Dozens of new political organizations vied for voters’ attention. Out of the confusion, two emerged as true contenders. One grew out of the slavery controversy, a coalition of indignant antislavery Northerners. The other arose from an entirely different split in American society, between native Protestants and Roman Catholic immigrants.

The American Promise: Printed Page 387

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 356

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 405

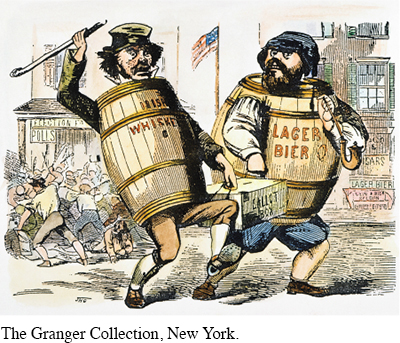

Page 388The wave of immigrants that arrived in America from 1845 to 1855 produced a nasty backlash among Protestant Americans, who feared that the Republic was about to drown in a sea of Roman Catholics from Ireland and Germany (see Figure 12.1, “Antebellum Immigration, 1840–1860” in chapter 12). Nativists (individuals who were anti-

The Know-

The Know-

The Republican creed tapped into the basic beliefs and values of Northerners. Slavery, Republicans believed, degraded the dignity of white labor by associating work with blacks and servility. As evidence, they pointed to the South, where, one Republican claimed, nonslaveholding whites “retire to the outskirts of civilization, where they live a semi-

Only by restricting slavery to the South, Republicans believed, could free labor flourish elsewhere. In the North, one Republican declared in 1854, “every man holds his fortune in his own right arm; and his position in society, in life, is to be tested by his own individual character.” Without slavery, western territories would provide vast economic opportunity for free men. Powerful images of liberty and opportunity attracted a wide range of Northerners to the Republican cause.

Women as well as men rushed to the new Republican Party. Indeed, three women helped found the party in Ripon, Wisconsin, in 1854. Although they could not vote and suffered from other legal handicaps, women nevertheless participated in partisan politics by writing campaign literature, marching in parades, giving speeches, and lobbying voters. Women’s antislavery fervor attracted them to the Republican Party, and participation in party politics in turn nurtured the woman’s rights movement. Susan B. Anthony, who attended Republican meetings throughout the 1850s, found that her political activity made her disfranchisement all the more galling. She and other women in the North worked on behalf of antislavery and woman suffrage and the right of married women to control their own property. (See “Experiencing the American Promise: ‘A Purse of Her Own’: Petitioning for the Right to Own Property.”)