The American Promise: Printed Page 381

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 351

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 399

The Fugitive Slave Act

The issue of runaway slaves was as old as the Constitution, which contained a provision for the return of any “person held to service or labor in one state” who escaped to another. In 1793, a federal law gave muscle to the provision by authorizing slave owners to enter other states to recapture their slave property. Proclaiming the 1793 law a license to kidnap free blacks, northern states in the 1830s began passing “personal liberty laws” that provided fugitives with some protection.

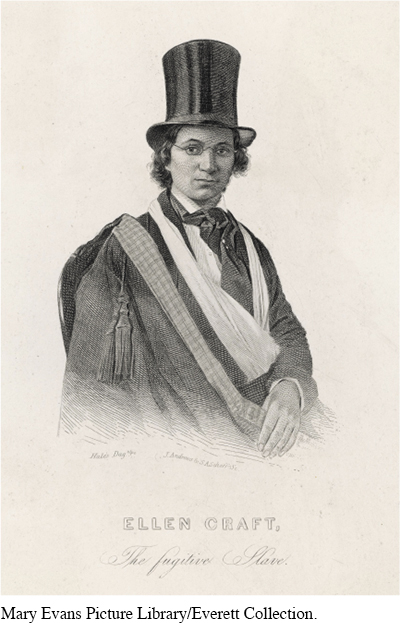

Some northern communities also formed vigilance committees to help runaways. Each year, a few hundred slaves escaped into free states and found friendly northern “conductors” who put them aboard the underground railroad, which was not a railroad at all but a series of secret “stations” (hideouts) on the way to Canada. Harriet Tubman, an escaped slave from Maryland, returned more than a dozen times and guided more than three hundred slaves to freedom in this way.

Furious about northern interference, Southerners in 1850 insisted on the stricter fugitive slave law that was part of the Compromise. According to the Fugitive Slave Act, to seize an alleged slave, a slaveholder simply had to appear before a commissioner and swear that the runaway was his. The commissioner earned $10 for every individual returned to slavery but only $5 for those set free. Most galling to Northerners, the law stipulated that all citizens were expected to assist officials in apprehending runaways. That required Northerners to become slave catchers.

The American Promise: Printed Page 381

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 351

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 399

Page 382In Boston in February 1851, an angry crowd overpowered federal marshals and snatched a runaway named Shadrach from a courtroom, put him on the underground railroad, and whisked him off to Canada. Three years later, when another Boston crowd rushed the courthouse in a failed attempt to rescue runaway Anthony Burns, a guard was shot dead. Martha Russell was among the angry crowd that watched Burns being escorted to the ship that would return him to Virginia. “Did you ever feel every drop of blood in you boiling and seething, throbbing and burning, until it seemed you should suffocate?” she asked. “I have felt all this today. I have seen that poor slave, Anthony Burns, carried back to slavery.”

To white Southerners, it seemed that fanatics of the “higher law” creed had whipped Northerners into a frenzy of massive resistance. Actually, the overwhelming majority of fugitives claimed by slaveholders were reenslaved peacefully. But brutal enforcement of the unpopular law had a radicalizing effect in the North, particularly in New England. Textile mill owner Amos A. Lawrence said that “we went to bed one night old fashioned, conservative, Compromise Union Whigs & waked up stark mad abolitionists.” He exaggerated, but to Southerners, Northerners had betrayed the Compromise and the Constitution. “The continued existence of the United States as one nation,” warned the Southern Literary Messenger, “depends upon the full and faithful execution of the Fugitive Slave Bill.”