The American Promise: Printed Page 444

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 405

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 463

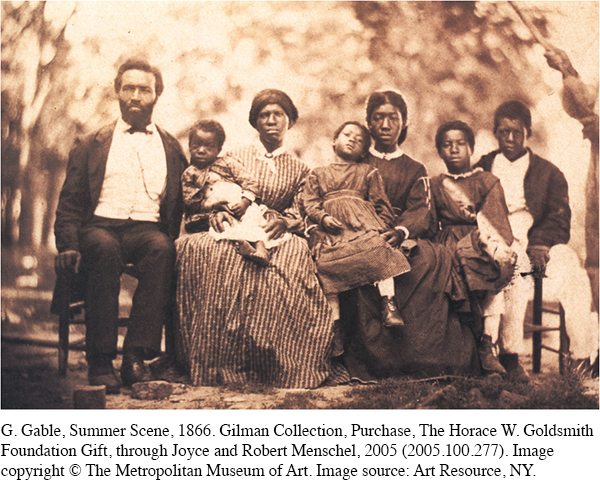

The African American Quest for Autonomy

The American Promise: Printed Page 444

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 405

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 463

Page 444Ex-

To whites, emancipation looked like pure anarchy. Blacks, they said, had reverted to their natural condition: lazy, irresponsible, and wild. Actually, former slaves were experimenting with freedom, but they could not long afford to roam the countryside, neglect work, and casually provoke whites. Soon, most were back at work in whites’ kitchens and fields.

But they continued to dream of land and independence. “The way we can best take care of ourselves is to have land,” one former slave declared in 1865, “and turn it and till it by our own labor.” Another group of former slaves in South Carolina declared that they wanted land, “not a Master or owner[,] Neither a driver with his Whip.”

The American Promise: Printed Page 444

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 405

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 463

Page 445Slavery had deliberately kept blacks illiterate, and freedmen emerged from bondage eager to learn to read and write. “I wishes the Childern all in School,” one black veteran asserted. “It is beter for them then to be their Surveing a mistes [mistress].” Freemen looked on schools as “first proof of their independence.”

The restoration of broken families was another persistent black aspiration. Thousands of freedmen took to the roads in 1865 to look for kin who had been sold away or to free those who were being held illegally as slaves. A black soldier from Missouri wrote his daughters that he was coming for them. “I will have you if it cost me my life,” he declared. “Your Miss Kitty said that I tried to steal you,” he told them. “But I’ll let her know that god never intended for a man to steal his own flesh and blood.” And he swore that “if she meets me with ten thousand soldiers, she [will] meet her enemy.”

Independent worship was another continuing aspiration. African Americans greeted freedom with a mass exodus from white churches, where they had been required to worship when slaves. Some joined the newly established southern branches of all-

REVIEW To what extent did Lincoln’s wartime plan for reconstruction reflect the concerns of newly freed slaves?