The American Promise: Printed Page 484

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 442

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 501

Life on the Comstock Lode

By 1859, refugees from California’s played-

To exploit even potentially valuable silver claims required capital and expensive technology well beyond the means of the prospector. An active San Francisco stock market sprang up to finance operations on the Comstock. Shrewd businessmen soon recognized that the easiest way to get rich was to sell their claims or to form mining companies and sell shares of stock. The most unscrupulous mined the wallets of gullible investors by selling shares in bogus mines. Speculation, misrepresentation, and outright thievery ran rampant. In twenty years, more than $300 million poured from the earth in Nevada alone, most of it going to speculators in San Francisco.

The promise of gold and silver drew thousands to the mines of the West. As Mark Twain observed in Virginia City’s Territorial Enterprise, “All the peoples of the earth had representative adventures in the Silverland.” Irish, Chinese, Germans, English, Scots, Welsh, Canadians, Mexicans, Italians, Scandinavians, French, Swiss, Chileans, and other South and Central Americans came to share in the bonanza. With them came a sprinkling of Russians, Poles, Greeks, Japanese, Spaniards, Hungarians, Portuguese, Turks, Pacific Islanders, and Moroccans, as well as other North Americans, African Americans, and American Indians. This polyglot population, typical of mining boomtowns, made Virginia City in the 1870s more cosmopolitan than New York or Boston. In the part of Utah Territory that eventually became Nevada, as many as 30 percent of the people came from outside the United States, compared to 25 percent in New York and 21 percent in Massachusetts.

The American Promise: Printed Page 484

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 442

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 501

Page 485Irish immigrants formed the largest ethnic group in the mining district. In Virginia City, fully one-

The discovery of precious metals on the Comstock spelled disaster for the Indians. No sooner had the miners struck pay dirt than they demanded that army troops “hunt Indians” and establish forts to protect transportation to and from the diggings. This sudden and dramatic intrusion left Nevada’s native tribes—

In 1873, Comstock miners uncovered a new vein of ore, a veritable cavern of gold and silver. This “Big Bonanza” speeded the transition from small-

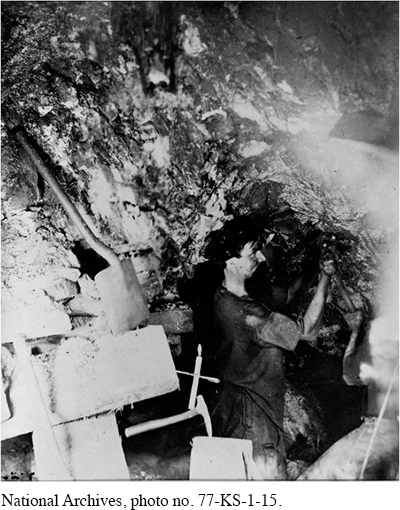

New technology eliminated some of the dangers of mining but often created new ones. In the hard-

The mining towns of the “Wild West” are often portrayed as lawless outposts, filled with saloons and rough gambling dens and populated almost exclusively by men. The truth is more complex, as Virginia City’s development attests. An established urban community built to serve an industrial giant, Virginia City in its first decade boasted churches, schools, theaters, an opera house, and hundreds of families. By 1870, women composed 30 percent of the population, and 75 percent of the women listed their occupation in the census as housekeeper. Mary McNair Mathews, a widow from Buffalo, New York, who lived on the Comstock in the 1870s, worked as a teacher, nurse, seamstress, laundress, and lodging-

By 1875, Virginia City boasted a population of 25,000 people, making it one of the largest cities between St. Louis and San Francisco. The city, dubbed the “Queen of the Comstock,” hosted American presidents as well as legions of lesser dignitaries. Virginia City represented, in the words of a recent chronicler, “the distilled essence of America’s newly established course—