The American Promise: Printed Page 486

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 444

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 504

Chapter Chronology

The Diverse Peoples of the West

The American Promise: Printed Page 486

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 444

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 504

Page 486The West of the late nineteenth century was a polyglot place, as much so as the big cities of the East. The sheer number of peoples who mingled in the West produced a complex blend of racism and prejudice. One historian has noted, not entirely facetiously, that there were at least eight oppressed “races” in the West—Indians, Latinos, Chinese, Japanese, blacks, Mormons, strikers, and radicals.

African Americans who ventured out to the territories faced hostile settlers determined to keep the West “for whites only.” In response, they formed all-black communities such as Nicodemus, Kansas. That settlement, founded by thirty black Kentuckians in 1877, grew to a community of seven hundred by 1880. Isolated and often separated by great distances, small black settlements grew up throughout the West, in Nevada, Utah, and the Pacific Northwest, as well as in Kansas. Black soldiers who served in the West during the Indian wars often stayed on as settlers. Called buffalo soldiers because Native Americans thought their hair resembled that of the bison, these black troops numbered up to 25,000. In the face of discrimination, poor treatment, and harsh conditions, the buffalo soldiers served with distinction and boasted the lowest desertion rate in the army.

Hispanic peoples had lived in Texas and the Southwest since Juan de Oñate led pioneer settlers up the Rio Grande in 1598. Hispanics had occupied the Pacific coast since San Diego was founded in 1769. Overnight, they were reduced to a “minority” after the United States annexed Texas in 1845 and took land stretching to California after the Mexican-American War ended in 1848. At first, the Hispanic owners of large ranchos in California, New Mexico, and Texas greeted conquest as an economic opportunity. But racial prejudice soon ended their optimism. Californios (Mexican residents of California), who had been granted American citizenship by the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (1848), faced discrimination by Anglos who sought to keep them out of California’s mines and commerce. Whites illegally squatted on rancho land while protracted litigation over Spanish and Mexican land grants forced the Californios into court. Although the U.S. Supreme Court eventually validated most of their claims, it took so long—seventeen years on average—that many Californios sold their property to pay taxes and legal bills.

Swindles, trickery, and intimidation dispossessed scores of Californios. Many ended up segregated in urban barrios (neighborhoods) in their own homeland. Their percentage of California’s population declined from 82 percent in 1850 to 19 percent in 1880 as Anglos migrated to the state. In New Mexico and Texas, Mexicans remained a majority of the population but became increasingly impoverished as Anglos dominated business and took the best jobs. Skirmishes between Hispanics and whites in northern New Mexico over the fencing of the open range lasted for decades. Groups of Hispanics with names such as Las Manos Negras (the Black Hands) cut fences and burned barns. In Texas, violence along the Rio Grande pitted Tejanos (Mexican residents of Texas) against the Texas Rangers, who saw their role as “keeping Mexicans in their place.”

Mormons, too, faced prejudice and hostility. The followers of Joseph Smith, the founder and prophet of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, fled west to Utah Territory in 1844 to avoid religious persecution. They believed they had a divine right to the land, and their messianic militancy made others distrust them. The Mormon practice of polygamy (church leader Brigham Young had twenty-three wives) also came under attack. To counter the criticism of polygamy, the Utah territorial legislature gave women the right to vote in 1870, the first universal woman suffrage act in the nation. (Wyoming had granted suffrage to white women in 1869.) Although women’s rights advocates argued that the newly enfranchised women would “do away with the horrible institution of polygamy,” it remained in force. Not until 1890 did the church hierarchy yield to pressure and renounce polygamy. The fierce controversy over polygamy postponed statehood for Utah until 1896.

The American Promise: Printed Page 486

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 444

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 504

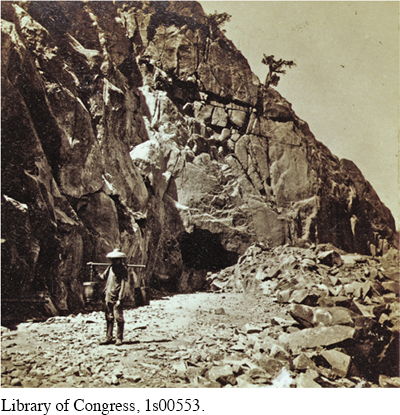

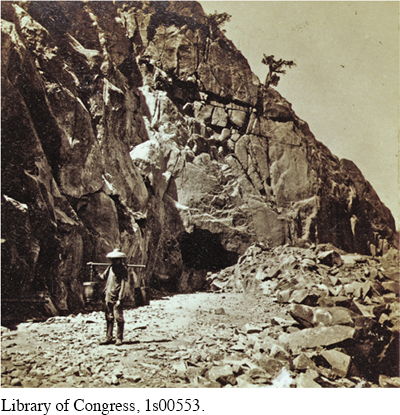

Page 487The Chinese suffered the most brutal treatment of all the newcomers at the hands of employers and other laborers. Drawn by the promise of gold, more than 20,000 Chinese had joined the rush to California by 1852. Miners determined to keep “California for Americans” succeeded in passing prohibitive foreign license laws to keep the Chinese out of the mines. But Chinese immigration continued. In the 1860s, when white workers moved on to find riches in the bonanza mines of Nevada, Chinese laborers took jobs abandoned by the whites. Railroad magnate Charles Crocker hired Chinese gangs to work on the Central Pacific, reasoning that “the race that built the Great Wall” could lay tracks across the treacherous Sierra Nevada. Some 10,000 Chinese, representing 90 percent of Crocker’s workforce, completed America’s first transcontinental railroad in 1869.

VISUAL ACTIVITYVaqueros in a Horse Corral, 1877 In this exciting scene, artist James Walker captures the skill of Hispanic vaqueros lassoing horses in a Texas corral. As Anglo settlers gradually displaced Hispanic landholders across the West, the domain of the rancho gradually declined, as did a way of life.READING THE IMAGE: What about the painting tells you that these are Hispanic cowboys and not Anglo cowboys?CONNECTIONS: In another twenty years, what would these vaqueros likely be doing for a living?

Private Collection/Peter Newark Pictures/Bridgeman Images.

By 1870, more than 63,000 Chinese immigrants lived in America, 77 percent of them in California. A 1790 federal statute that limited naturalization to “white persons” was modified after the Civil War to extend naturalization to blacks (“persons of African descent”). But the Chinese and other Asians continued to be denied access to citizenship. As perpetual aliens, they constituted a reserve army of transnational laborers that many saw as a threat to American labor.

Chinese Railroad Worker, ca. 1867 This photograph of a lone Chinese laborer carrying a shoulder pole illustrates the magnitude of the task workers faced in the Sierra Nevada. This worker stands in front of what would become Tunnel no. 8, one of the innumerable tunnels carved by hand through the granite. Six years of backbreaking work culminated in the epic achievement of the Central Pacific Railroad.

Library of Congress, 1s00553.

In 1876, the Workingmen’s Party formed to fight for Chinese exclusion. Racial and cultural animosities stood at the heart of anti-Chinese agitation. Denis Kearney, the fiery San Francisco leader of the movement, made clear this racist bent when he urged legislation to “expel every one of the moon-eyed lepers.” Nor was California alone in its anti-immigrant nativism. As the country confronted growing ethnic and racial diversity with the rising tide of global immigration in the decades following the Civil War, many questioned the principle of racial equality at the same time they argued against the assimilation of “nonwhite” groups. In this climate, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882, effectively barring Chinese immigration and setting a precedent for further immigration restrictions.

The American Promise: Printed Page 486

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 444

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 504

Page 488The Chinese Exclusion Act led to a sharp drop in the Chinese population—from 105,465 in 1880 to 89,863 in 1900—because Chinese immigrants, overwhelmingly male, did not have families to sustain their population. Eventually, Japanese immigrants, including women as well as men, replaced the Chinese, particularly in agriculture. As “nonwhite” immigrants, they could not become naturalized citizens, but their children born in the United States claimed the rights of citizenship. Japanese parents, seeking to own land, purchased it in their children’s names. Although anti-Asian prejudice remained strong in California and elsewhere in the West, Asian immigrants formed an important part of the economic fabric of the western United States.

REVIEW What role did mining play in shaping the society and economy of the American West?