The American Promise: Printed Page 489

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 446

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 507

Moving West: Homesteaders and Speculators

The American Promise: Printed Page 489

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 446

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 507

Page 489A Missouri homesteader remembered packing as her family pulled up stakes and headed west to Oklahoma in 1890. “We were going to God’s Country,” she wrote. “You had to work hard on that rocky country in Missouri. I was glad to be leaving it. . . . We were going to a new land and get rich.”

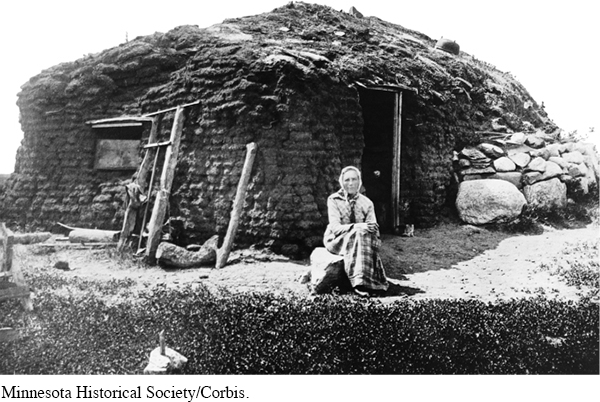

Settlers who headed west in search of “God’s Country” faced hardship, loneliness, and deprivation. To carve a farm from the raw prairie of Iowa, the plains of Nebraska, or the forests of the Pacific Northwest took more than fortitude and backbreaking toil. It took luck. Blizzards, tornadoes, grasshoppers, hailstorms, drought, prairie fires, accidental death, and disease were only a few of the catastrophes that could befall even the best farmer. Homesteaders on free land still needed as much as $1,000 for a house, a team of farm animals, a well, fencing, and seed. Poor farmers called “sodbusters” did without even these basics, living in houses made from sod (blocks of grass-

“Father made a dugout and covered it with willows and grass,” one Kansas girl recounted. When it rained, the dugout flooded, and “we carried the water out in buckets, then waded around in the mud until it dried.” Rain wasn’t the only problem. “Sometimes the bull snakes would get in the roof and now and then one would lose his hold and fall down on the bed. . . . Mother would grab the hoe . . . and after the fight was over Mr. Bull Snake was dragged outside.”

For women on the frontier, obtaining simple daily necessities such as water and fuel meant backbreaking labor. Out on the plains, where water was scarce, women often had to trudge to the nearest creek or spring. “A yoke was made to place across [Mother’s] shoulders, so as to carry at each end a bucket of water,” one daughter recollected, “and then water was brought a half mile from spring to house.” Gathering fuel was another heavy chore. Without ready sources of coal or firewood, the most prevalent fuel was “chips”—chunks of dried cattle and buffalo dung, found in abundance on the plains.

Despite the hardships, some homesteaders succeeded in building comfortable lives. The dugout made way for the sod hut—

As land grew scarce on the prairie in the 1870s, farmers began to push farther west, moving into western Kansas, Nebraska, and eastern Colorado—

The American Promise: Printed Page 489

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 446

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 507

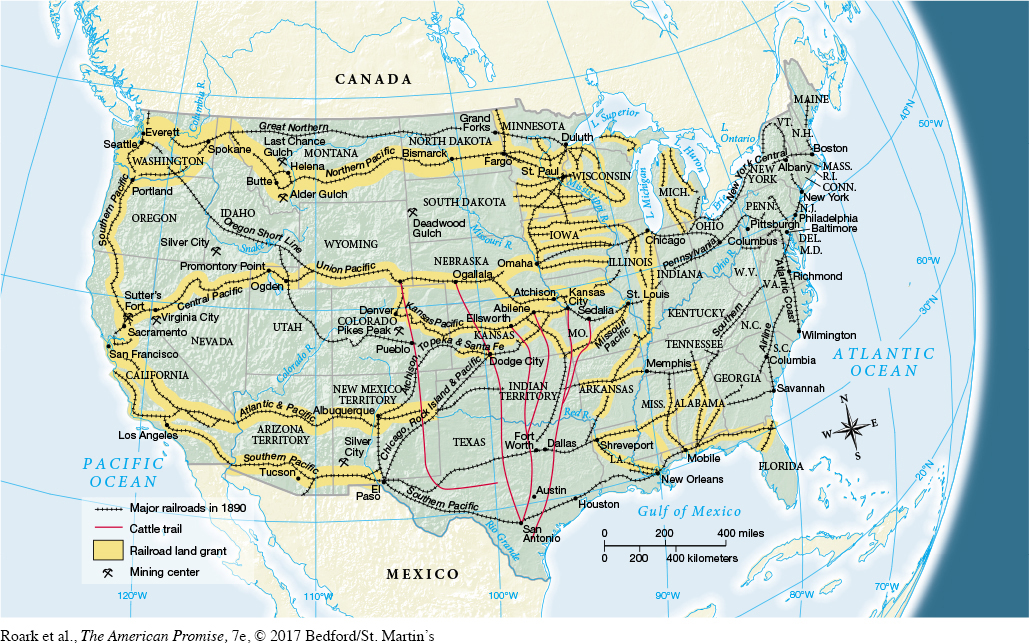

Page 491Fever for fertile land set off a series of spectacular land runs in Oklahoma. When two million acres of land in former Indian Territory opened for settlement in 1889, thousands of homesteaders massed on the border. At the opening pistol shot, “with a shout and a yell the swift riders shot out, then followed the light buggies or wagons,” a reporter wrote. “Above all, a great cloud of dust hover[ed] like smoke over a battlefield.” By nightfall, Oklahoma boasted two tent cities with more than ten thousand residents. In the last frenzied land rush on Oklahoma’s Cherokee strip in 1893, several settlers were killed in the stampede, and nervous men guarded their claims with rifles. As public land grew scarce, the hunger for land grew fiercer for both farmers and ranchers.

Barbed wire, invented in 1874, revolutionized the cattle business and sounded the death knell for the open range. As the largest ranches in Texas began to fence, nasty fights broke out between big ranchers and “fence cutters,” who resented the end of the open range. One old-

The American Promise: Printed Page 489

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 446

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 507

Page 492On the range, the cowboy gave way to the cattle king and, like the miner, became a wage laborer. Many cowboys were African Americans (as many as five thousand in Texas alone). Writers of western literature chose to ignore the presence of black cowboys like Deadwood Dick (Nat Love), who was portrayed as a white man in the dime novels of the era.

By 1886, cattle overcrowded the range. Severe blizzards during the winter of 1886–