The American Promise: Printed Page 472

BEYOND AMERICA’S BORDERS

The American Promise: Printed Page 472

Page 472Imperialism, Colonialism, and the Treatment of the Sioux and the Zulu

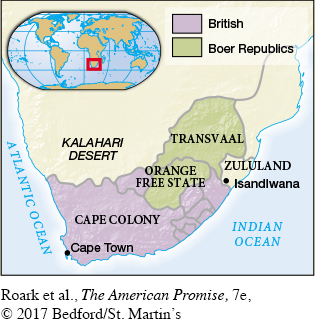

Viewed through the lens of colonialism, the British war with the Zulu in South Africa offers a compelling contrast to the war of the United States against the Lakota Sioux. The Zulu, like the Sioux, came to power as a result of devastating intertribal warfare. In the area that is today the KwaZulu-

In 1806, the British seized the Cape of Good Hope to secure shipping interests, leading to conflicts with Dutch-

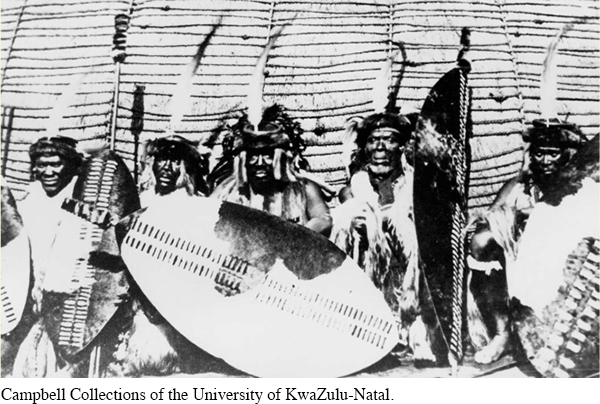

The Zulu lived in a highly complex society, with regiments of warriors arranged by age and bound to local chiefs under the supreme command of the Zulu king. During his harsh reign, King Shaka inspected his regiments after each battle and put cowards to death on the spot. Young men could not start their own households without the local chief’s permission, thus ensuring an ample stock of warriors and making the Zulu army, in the words of one English observer, “a celibate, man-

The British entered the fray in 1879, sparking the Anglo-

With aims of both placating the Boers and securing a source of labor for British economic expansion—

When news of Isandlwana reached London, commentators compared the massacre to Custer’s defeat at the Battle of the Little Big Horn and noted that native forces armed with spears had defeated a modern army.

The British immediately launched unconditional war against the Zulu. In the ensuing battles, neither side took prisoners. The Zulu beat the British twice more, but after seven months the British finally routed the Zulu army and abandoned Zululand to its fate—

Historians would later compare the British victory to the U.S. Army’s defeat of the Sioux in the American West, but the Zulu and Sioux met different economic fates. As Shepstone hinted in 1878, the British goal had been to subdue the Zulu and turn them into cheap labor. Compared to the naked economic exploitation of the Zulu, the U.S. policy toward the Sioux, with its forced assimilation on reservations and its misguided attempts to turn the nomadic tribes into sedentary, God-

Both the Little Big Horn and Isandlwana became legends that spawned a romantic image of the “noble savage”: fierce in battle, honored in defeat. Describing this myth, historian James Gump, who has chronicled the subjugation of the Sioux and the Zulu, observed, “Each western culture simultaneously dehumanized and glamorized the Sioux and Zulu.” Gump noted that the noble savage mythology was “a product of the racist ideologies of the late nineteenth century as well as the guilt and compassion associated with the bloody costs of empire building.” The imperial powers of Britain and the United States defeated indigenous rivals and came to dominate their lands (and, in the case of the Zulu, their labor) in the global expansion that marked the nineteenth century.

Questions for Analysis

Summarize the Argument: How was the British war with the Zulu both similar to and different from the American war with the Sioux?

Ask Historical Questions: Compare the fate of the defeated Zulu with that of the Lakota Sioux.

Recognize Viewpoints: Policy toward indigenous peoples in the United States and Great Britain in the nineteenth century differed. What distinguished them?