The American Promise: Printed Page 475

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 432

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 493

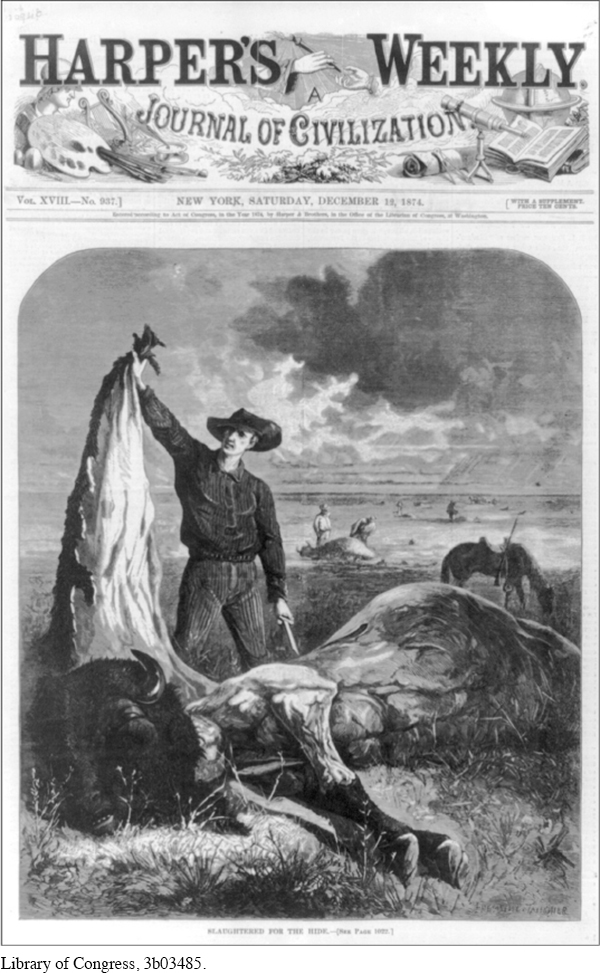

The Decimation of the Great Bison Herds

The American Promise: Printed Page 475

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 432

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 493

Page 475After the Civil War, the accelerating pace of industrial expansion brought about the near extinction of the American bison (buffalo). By 1850, the dynamic ecology of the Great Plains, with its droughts, fires, and blizzards, along with the demands of Indian buffalo-

In the 1870s, industrial demand for heavy leather belting used in machinery and the development of larger, more accurate rifles combined to hasten the slaughter of the bison. The nation’s transcontinental railroad systems cut the range in two and divided the dwindling herds. For the Sioux and other nomadic tribes of the plains, the buffalo constituted a way of life—

Although the army took credit for the conquest of the Plains Indians, the decimation of the great bison herds was largely responsible for the Indians’ fate. With their food supply gone, Indians had to choose between starvation and the reservation. “A cold wind blew across the prairie when the last buffalo fell,” the great Sioux leader Sitting Bull lamented, “a death wind for my people.”

On the southern plains in 1867, more than five thousand warring Comanches, Kiowas, and Southern Arapahos gathered at Medicine Lodge Creek in Kansas to negotiate the Treaty of Medicine Lodge, hoping to preserve limited land and hunting by moving the tribe to a reservation. Three years after the treaty became law, hide hunters poured into the region; within a decade, they had nearly exterminated the southern bison herds. Luther Standing Bear recounted the sight and stench: “I saw the bodies of hundreds of dead buffalo lying about, just wasting, and the odor was terrible. . . . They were letting our food lie on the plains to rot.” Once an estimated 40 million bison roamed the West; by 1895, fewer than 1,000 remained. With the buffalo gone, the Indians faced starvation and reluctantly moved onto the reservations.