The American Promise: Printed Page 508

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 466

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 529

J. P. Morgan and Finance Capitalism

John Pierpont Morgan, the preeminent finance capitalist of the late nineteenth century, loathed competition and sought whenever possible to eliminate it by substituting consolidation and central control. Morgan’s passion for order made him the architect of business mergers. At the turn of the twentieth century, he dominated American banking, exerting an influence so powerful that his critics charged he controlled a vast “money trust” even more insidious than Rockefeller’s Standard Oil.

Morgan acted as a power broker in the reorganization of the railroads and the creation of industrial giants such as General Electric. When the railroads collapsed, Morgan took over and eliminated competition by creating what he called “a community of interest.” By the time he finished “Morganizing” the railroads, a handful of directors controlled two-

The American Promise: Printed Page 508

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 466

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 529

Page 509In 1898, Morgan moved into the steel industry, directly challenging Andrew Carnegie. The pugnacious Carnegie cabled his partners in the summer of 1900: “Action essential: crisis has arrived . . . have no fear as to the result; victory certain.” The press trumpeted news of the impending fight between the feisty Scot and the haughty Wall Street banker. But for all his belligerence, the sixty-

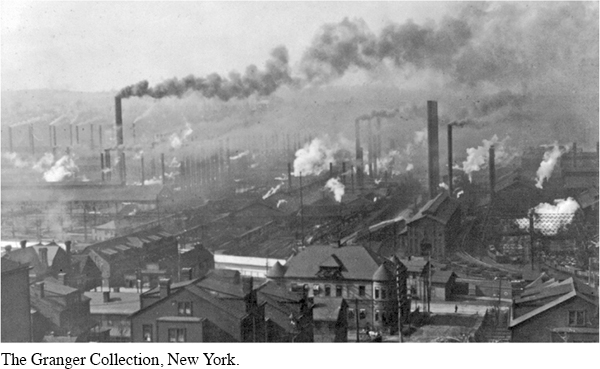

Morgan’s acquisition of Carnegie Steel signaled the passing of the old entrepreneurial order personified by Andrew Carnegie and the arrival of a new anonymous corporate world. Morgan quickly moved to pull together Carnegie’s chief competitors to form a huge new corporation, United States Steel, known today as USX. Created in 1901 and capitalized at $1.4 billion, U.S. Steel was the largest corporation in the world.

Even more than Carnegie or Rockefeller, Morgan left his stamp on the twentieth century and formed the model for corporate consolidation that economists and social scientists justified with a new social theory later called social Darwinism.