The American Promise: Printed Page 512

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 468

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 532

Sectionalism and the New South

After the end of Reconstruction, most white voters in the former Confederate states remained loyal Democrats, creating the so-

The South’s economy, devastated by the war, foundered at the same time the North experienced an unprecedented industrial boom. Soon an influential group of southerners called for a New South modeled on the industrial North. Henry Grady, the ebullient young editor of the Atlanta Constitution, used his paper’s influence to exhort the South to use its natural advantages—

The railroads came first, opening up the region for industrial development. Southern railroad mileage grew fourfold from 1865 to 1890. The number of cotton spindles also soared as textile mill owners abandoned New England in search of the cheap labor and proximity to raw materials promised in the South. By 1900, the South had become the nation’s leading producer of cloth, and more than 100,000 southerners, many of them women and children, worked in the region’s textile mills.

The New South prided itself most on its iron and steel industry, which grew up in the area surrounding Birmingham, Alabama. During this period, the smokestack replaced the white-

The American Promise: Printed Page 512

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 468

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 532

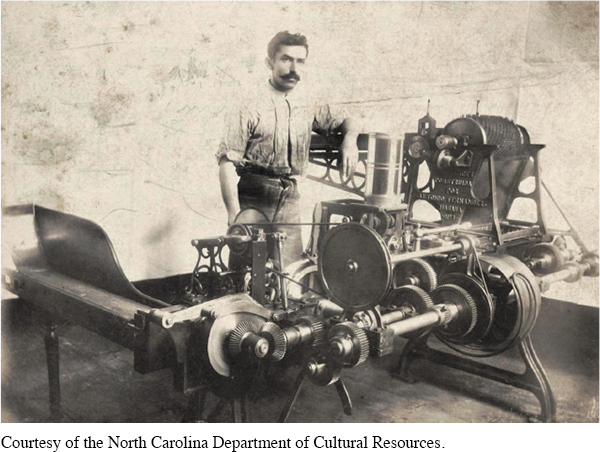

Page 513In only one industry did the South truly dominate—

In practical terms, the industrialized New South proved an illusion. Much of the South remained agricultural, caught in the grip of the insidious crop lien system (see “White Landlords, Black Sharecroppers” in chapter 16). White southern farmers, desperate to get out of debt, sometimes joined African Americans to pursue mutual political goals. Between 1865 and 1900, voters in every southern state experimented with political alliances that crossed the color line and threatened the status quo.