The American Promise: Printed Page 525

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 483

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 548

Introduction to Chapter 19

The American Promise: Printed Page 525

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 483

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 548

Page 52519

The City and Its Workers

1870–

CONTENT LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading and studying this chapter, you should be able to:

Identify the factors that led to rapid urbanization during the late nineteenth century. Describe how the social geography of the city changed and the reactions to those changes.

Describe the diversity of American labor, including the role of women and children in the workforce.

Understand why workers organized and how management responded to labor’s demands. Analyze the impact of the Great Strike of 1877, the Knights of Labor, the American Federation of Labor, and the Haymarket bombing.

Describe how notions of domesticity and everyday amusements reflected class divisions.

Identify the nature of city government in the late nineteenth century and the growth of city amenities. Explain Americans’ ambivalence toward cities.

“A TOWN THAT CRAWLED NOW STANDS ERECT, AND WE WHOSE backs were bent above the hearths know how it got its spine,” boasted a steelworker surveying New York City. Where once wooden buildings stood rooted in the mire of unpaved streets, cities of stone and steel sprang up in the last decades of the nineteenth century. The labor of millions of workers, many of them immigrants, laid the foundations for urban America.

No symbol better represented the new urban landscape than the Brooklyn Bridge, opened in May 1883. The great bridge soared over the East River in a single mile-

The American Promise: Printed Page 525

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 483

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 548

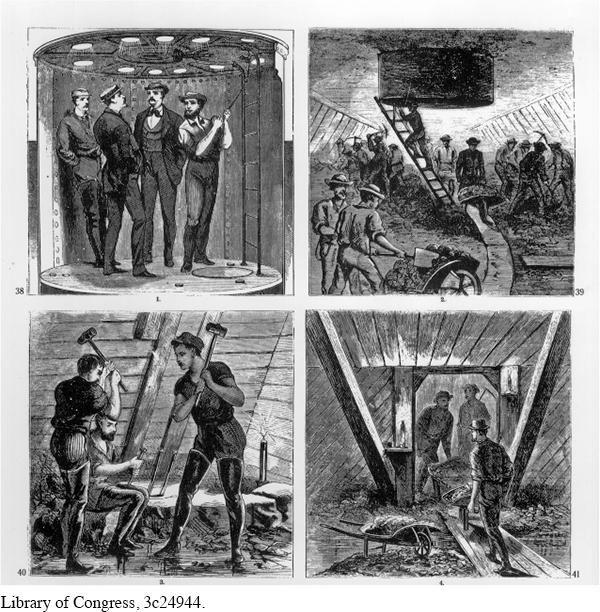

Page 526A scrawny sixteen-

The six of us were working naked to the waist in the small iron chamber with the temperature of about 80 degrees Fahrenheit: In five minutes the sweat was pouring from us, and all the while we were standing in icy water that was only kept from rising by the terrific pressure. No wonder the headaches were blinding.

By his fifth day, Harris quit. Many immigrant workers walked off the job, often as many as a hundred a week. But a ready supply of immigrants meant that new workers took up the digging, where they could earn in a day more than they made in a week in Ireland or Italy.

Begun in 1869, the bridge was the dream of builder John Roebling, who died in a freak accident almost as soon as construction began. Washington Roebling took over as chief engineer after his father’s death, routinely working twelve-

At the end of the nineteenth century, the Brooklyn Bridge stood as a symbol of many things: the industrial might of the United States; the labor of the nation’s immigrants; the ingenuity and genius of its engineers and inventors; the rise of iron and steel; and, most of all, the ascendancy of urban America. Poised on the brink of the twentieth century, the nation was shifting from a rural, agricultural society to an urban, industrial nation. The gap between rich and poor widened. In the burgeoning cities, tensions erupted into conflict as workers squared off to organize into labor unions and to demand safer working conditions, shorter hours, and better pay, sometimes with violent and bloody results. The explosive growth of the cities fostered political corruption as unscrupulous bosses and entrepreneurs cashed in on the building boom. Immigrants, political bosses, middle-

CHRONOLOGY

| 1869 |

|

| 1871 |

|

| 1873 |

|

| 1877 |

|

| 1880s |

|

| 1882 |

|

| 1883 |

|

| 1886 |

|

| 1890 |

|

| 1890s |

|

| 1892 |

|

| 1893 |

|

| 1895 |

|

| 1896 |

|

| 1897 |

|