The American Promise: Printed Page 541

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 498

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 564

The Great Railroad Strike of 1877

Economic depression following the panic of 1873 threw as many as three million people out of work. Those who were lucky enough to keep their jobs watched as pay cuts eroded wages until they could no longer feed their families. In the summer of 1877, the Baltimore and Ohio (B&O) Railroad announced a 10 percent wage cut at the same time it declared a 10 percent dividend to its stockholders. Angry brakemen in West Virginia, whose wages had already fallen from $70 to $30 a month, walked out on strike. One B&O worker described the hardship that drove him to take such desperate action: “We eat our hard bread and tainted meat two days old on the sooty cars up the road, and when we come home, find our wives complaining that they cannot even buy hominy and molasses for food.”

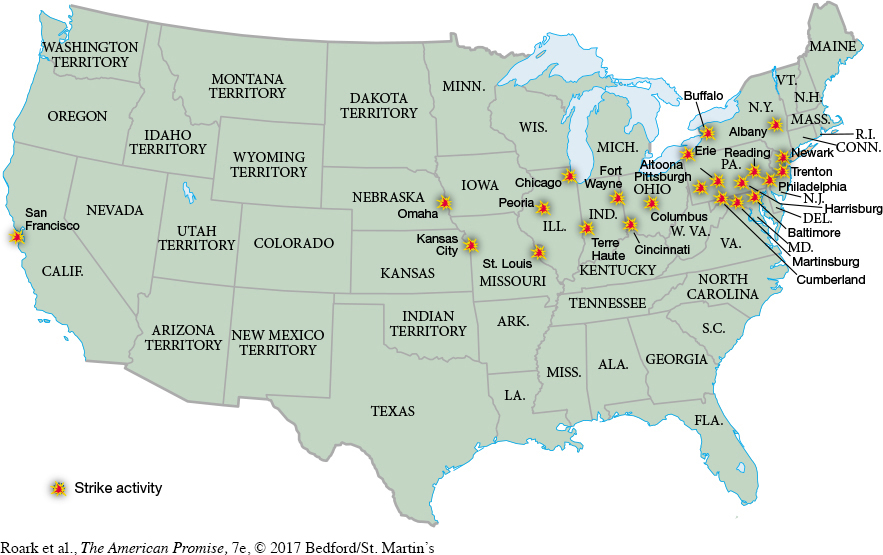

The West Virginia brakemen’s strike touched off the Great Railroad Strike of 1877, a nationwide uprising that spread rapidly to Pittsburgh and Chicago, St. Louis and San Francisco (Map 19.3). Within a few days, nearly 100,000 railroad workers had walked off the job. An estimated 500,000 sympathetic railway workers soon joined the strikers. In Reading, Pennsylvania, militiamen refused to fire on the strikers, saying, “We may be militiamen, but we are workmen first.” Rail traffic ground to a halt; the nation lay paralyzed.

The American Promise: Printed Page 541

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 498

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 564

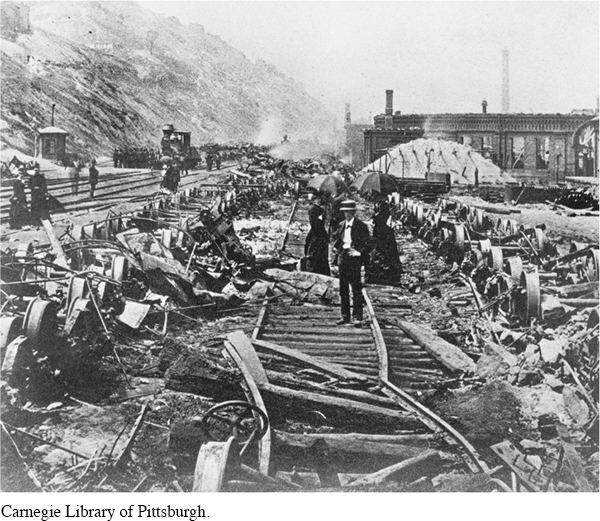

Page 542Violence erupted as the strike spread. In Pittsburgh, militia brought in from Philadelphia fired on the crowds, killing more than twenty people. Angry workers retaliated by reducing an area two miles long beside the tracks to rubble. Before the day ended, the militia shot twenty workers and the railroad sustained more than $2 million in property damage.

Within eight days, the governors of nine states, acting at the prompting of the railroad owners and managers, defined the strike as an “insurrection” and called for federal troops. President Rutherford B. Hayes, after hesitating briefly, called out the army. By the time the troops arrived, the violence had run its course. Federal troops did not shoot a single striker in 1877. But they struck a blow against labor by acting as strikebreakers—

Middle-

The American Promise: Printed Page 541

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 498

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 564

Page 543“The strikes have been put down by force,” President Hayes noted in his diary on August 5. “But now for the real remedy. Can’t something be done by education of the strikers, by judicious control of the capitalists, by wise general policy to end or diminish the evil? The railroad strikers, as a rule, are good men, sober, intelligent, and industrious.” While Hayes acknowledged the workers’ grievances, most businessmen condemned the idea of labor unions as agents of class warfare. For their part, workers quickly recognized that they held little power individually and flocked to join unions. As labor leader Samuel Gompers noted, the nation’s first national strike dramatized the frustration and unity of the workers and served as an alarm bell to labor “that sounded a ringing message of hope to us all.”