The American Promise: Printed Page 552

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 574

BEYOND AMERICA’S BORDERS

The American Promise: Printed Page 552

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 574

Page 552The World’s Columbian Exposition and Nineteenth-

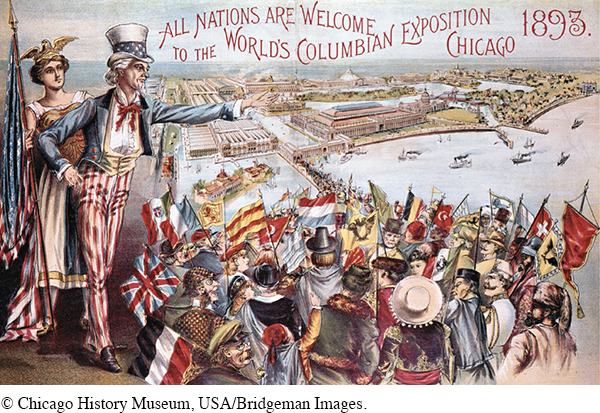

The 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, like the other great world’s fairs of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, represented a unique outgrowth of industrial capitalism and a testament to the expanding global market economy. The Chicago fair, named to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Columbus’s arrival in the New World (the organizers missed the deadline by a year), offered a cornucopia of international exhibits, testifying to growing international influences ranging from cultural to technological exchange.

Great cities vied to host the fairs, as much to promote commercial growth as to demonstrate cultural refinement. Each successive fair sought to outdo its predecessor. Chicago’s fair followed on the great success of the 1889 Universal Exposition in Paris, crowned by the 900-

The answer was to create from scratch an ideal White City with monumental architecture, landscaped grounds, and the world’s first Ferris wheel. The White City celebrated the classicism of the French Beaux Arts school, with massive geometric styling and elaborate detailing borrowed from Greek, Roman, and Renaissance architecture. Prairie architects Louis Sullivan and Frank Lloyd Wright later complained the fair was a “virus” that held back modern architecture for decades.

But beneath its Renaissance facade, the White City acted as an enormous emporium dedicated to the unabashed materialism of the Gilded Age. Fairgoers could view virtually every kind of manufactured product in the world inside the imposing Manufactures and Liberal Arts Building. As suited an industrial age, manufactured products and heavy machinery drew the largest crowds. Displays introduced visitors to the latest innovations, many the result of international influences. For five cents, fairgoers could put two hard rubber tubes into their ears and listen for the first time to a gramophone playing the popular tune “The Cat Came Back.” The invention, the work of a German immigrant, Emile Berliner, signaled the beginning of the recorded music industry. Later Thomas Edison claimed credit for a similar invention, calling it the phonograph.

Such international influences were evident throughout the Columbian Exposition. At the Tiffany pavilion, Louis Comfort Tiffany displayed jewelry and objects influenced by Japanese art forms. The Colt firearms factory, known throughout the world for its revolver, was already international in scope, having opened a factory in England in 1851. At the fair, Colt debuted its new automatic weapon, the machine gun—

All manner of foodstuffs tempted fairgoers—

By displaying technology in action, the White City tamed it and made it accessible to American and world consumers. The fair helped promote electric light and power, with its 90,000 electric lights, 5,100 arc lamps, electric fountains, an electric elevated railroad, and electric launches plying the lagoons. Fairgoers visited the Bell Telephone Company exhibit, marveled at General Electric’s huge dynamo (electric generator), and gazed into the future at the all-

Consumer culture received its first major expression and celebration at the fair. Not only did this world’s fair anticipate the mass marketing, packaging, and advertising of the twentieth century, but the vast array of products on display also cultivated the urge to consume. Thousands of concessionaires with products for sale sent a message that tied enjoyment inextricably to spending money and purchasing goods, both domestic and foreign. The Columbian Exposition encouraged the rise of a new middle-

The American Promise: Printed Page 552

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 574

Page 553Questions for Analysis

Summarize the Argument: To what extent was the Columbian Exposition simultaneously a commercial venture, a cultural display, and entertainment?

Consider the Context: How did the Columbian Exposition and the White City reflect changes in late-

Ask Historical Questions: What role did the fair play in popularizing new technologies?