The American Promise: Printed Page 532

MAKING HISTORICAL ARGUMENTS

The American Promise: Printed Page 532

Page 532What Happened to Urban Workers’ Standard of Living during the Gilded Age?

A relatively small number of factory owners and financiers enjoyed higher living standards during the Gilded Age. But what happened to the standard of living of urban workers, who made up 85 percent of city residents?

Since nearly all urban workers came from rural areas, a good way to assess what happened to their living standards is to compare them with those of farmers in the same period. Consider, for example, urban workers’ earnings, hours, and conditions of work; housing, food, and domestic labor.

Factory workers typically labored ten to twelve hours a day six days a week, for wages that averaged $500 to $750 a year. In a good year, the average farm family produced crops worth as much as $1,000. But since family members provided most farm labor (outside the southern states), they typically received room and board as compensation rather than cash wages. Even the low wages received by factory workers put some cash in their pockets, giving them choices about spending that farmers seldom had.

Factory hands worked long hours at grueling and often dangerous tasks. Farmwork, however, had its own dangers and typically began before dawn and lasted until after dark, as long as or longer than factory workdays. Farmwork was more varied and self-

Neither urban workers nor farmers enjoyed much economic security. Factory workers could be laid off or fired at any time for any reason. During the severe depressions in 1873 and 1893, unemployment sapped workers’ ability to support their families, causing extreme poverty and even starvation in many cities. Farmers’ ability to keep their heads above water depended on the uncertainties of weather, insect pests, and crop diseases. But they also suffered from declining agricultural prices during the era that made their cash crops worth less and less. Farmers protected their families from the starvation that stalked cities in hard times by growing food crops for their own consumption.

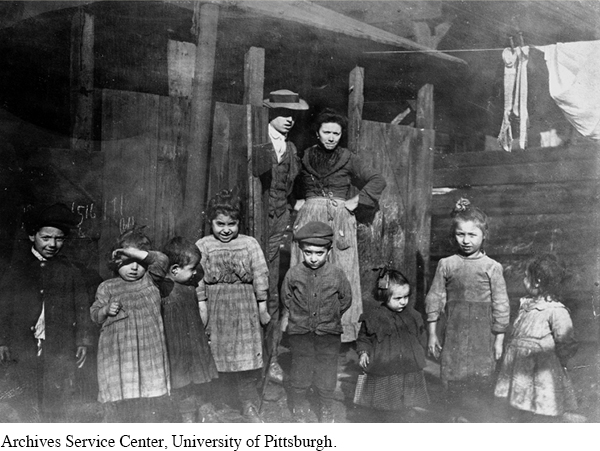

Squalid tenements that commonly housed immigrants in New York City made up only about 5 percent of urban housing in most other cities. The vast majority of urban working people resided in single-

Both urban workers and farmers enjoyed ample diets compared to their British or European counterparts. For the most part, however, urban working people had access to a greater variety of food choices than farmers, especially after canned foods became relatively common toward the end of the century. Workingmen could also buy at a local saloon a five-

Women did the taxing, never-

Overall, the living standards of urban working people resembled those of farm families in many ways, despite some important differences in wages, working conditions, and unhealthy waste disposal. In general, however, when compared with the rural lives that many urban workers left behind, it is clear that urban working people did not share the dramatic improvement in living standards that was enjoyed by the Gilded Age plutocrats.

Questions for Analysis

Summarize the Argument: How did the living standards of urban working people compare with those of farmers? With those of factory owners and financiers?

Analyze the Evidence: What role did wages and working conditions play in the living standards of urban working people?

Consider the Context: Given what happened to the living standards of urban working people in the Gilded Age, what motivations did they have to leave farms and move to cities?