The American Promise: Printed Page 12

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 11

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 12

Southwestern Cultures

Ancient Americans in present-

The American Promise: Printed Page 12

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 11

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 12

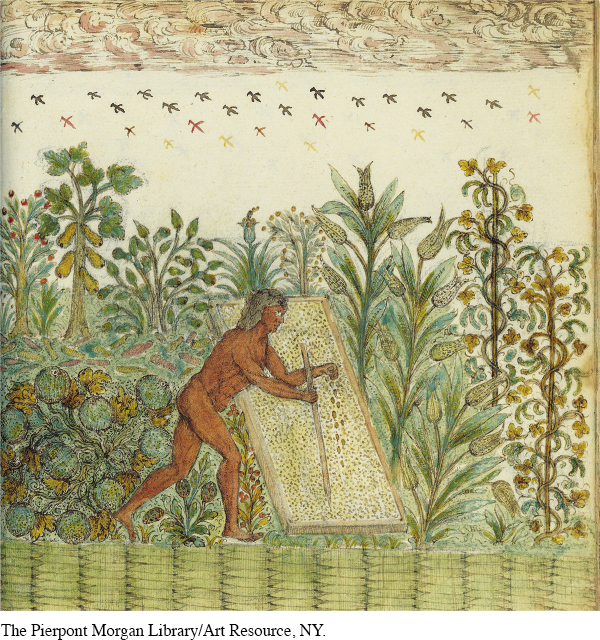

Page 13About 3500 BP, southwestern hunters and gatherers began to cultivate corn, their signature food crop. (See “Beyond America’s Borders: Corn: An Ancient American Legacy.”) The demands of corn cultivation encouraged hunter-

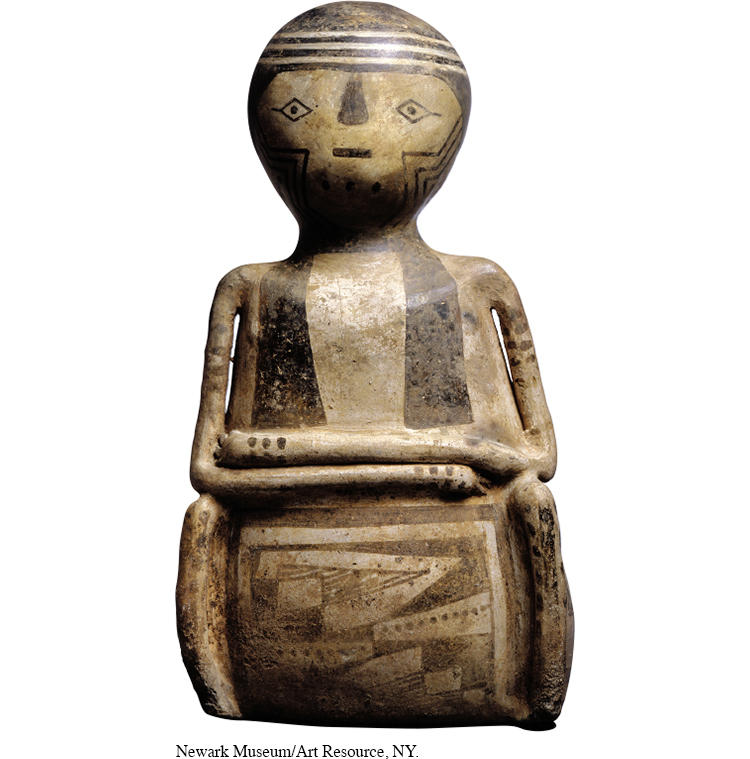

About AD 200, small farming settlements began to appear throughout southern New Mexico, marking the emergence of the Mogollon culture. Typically, a Mogollon settlement included a dozen pit houses, each made by digging out a pit about fifteen feet in diameter and a foot or two deep and then erecting poles to support a roof of branches or dirt. Larger villages usually had one or two bigger pit houses that may have been the predecessors of the circular kivas, the ceremonial rooms that became a characteristic of nearly all southwestern settlements. About AD 900, Mogollon culture began to decline, for reasons that remain obscure.

Around AD 500, while the Mogollon culture prevailed in New Mexico, other ancient people migrated from Mexico to southern Arizona and established the distinctive Hohokam culture. Hohokam settlements used sophisticated grids of irrigation canals to plant and harvest crops twice a year. Hohokam settlements reflected Mexican cultural practices that northbound migrants brought with them, including the building of sizable platform mounds and ball courts. About AD 1400, Hohokam culture declined for reasons that remain a mystery, although the rising salinity of the soil brought about by centuries of irrigation probably caused declining crop yields and growing food shortages.

The American Promise: Printed Page 12

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 11

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 12

Page 14

North of the Hohokam and Mogollon cultures, in a region that encompassed southern Utah and Colorado and northern Arizona and New Mexico, the Anasazi culture began to flourish about AD 100. The early Anasazi built pit houses on mesa tops and used irrigation much as did their neighbors to the south. Beginning around AD 1000, some Anasazi began to move to large, multistory cliff dwellings whose spectacular ruins still exist at Mesa Verde, Colorado, and elsewhere. Other Anasazi communities—