The American Promise: Printed Page 582

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 531

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 603

The Debate over American Imperialism

The American Promise: Printed Page 582

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 531

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 603

Page 581The American Promise: Printed Page 582

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 531

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 603

Page 582After a few brief campaigns in Cuba and Puerto Rico brought the Spanish-

Contemptuous of the Cubans, whom General William Shafter declared “no more fit for self-

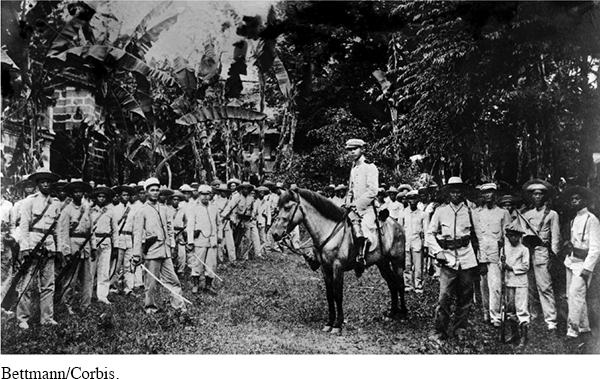

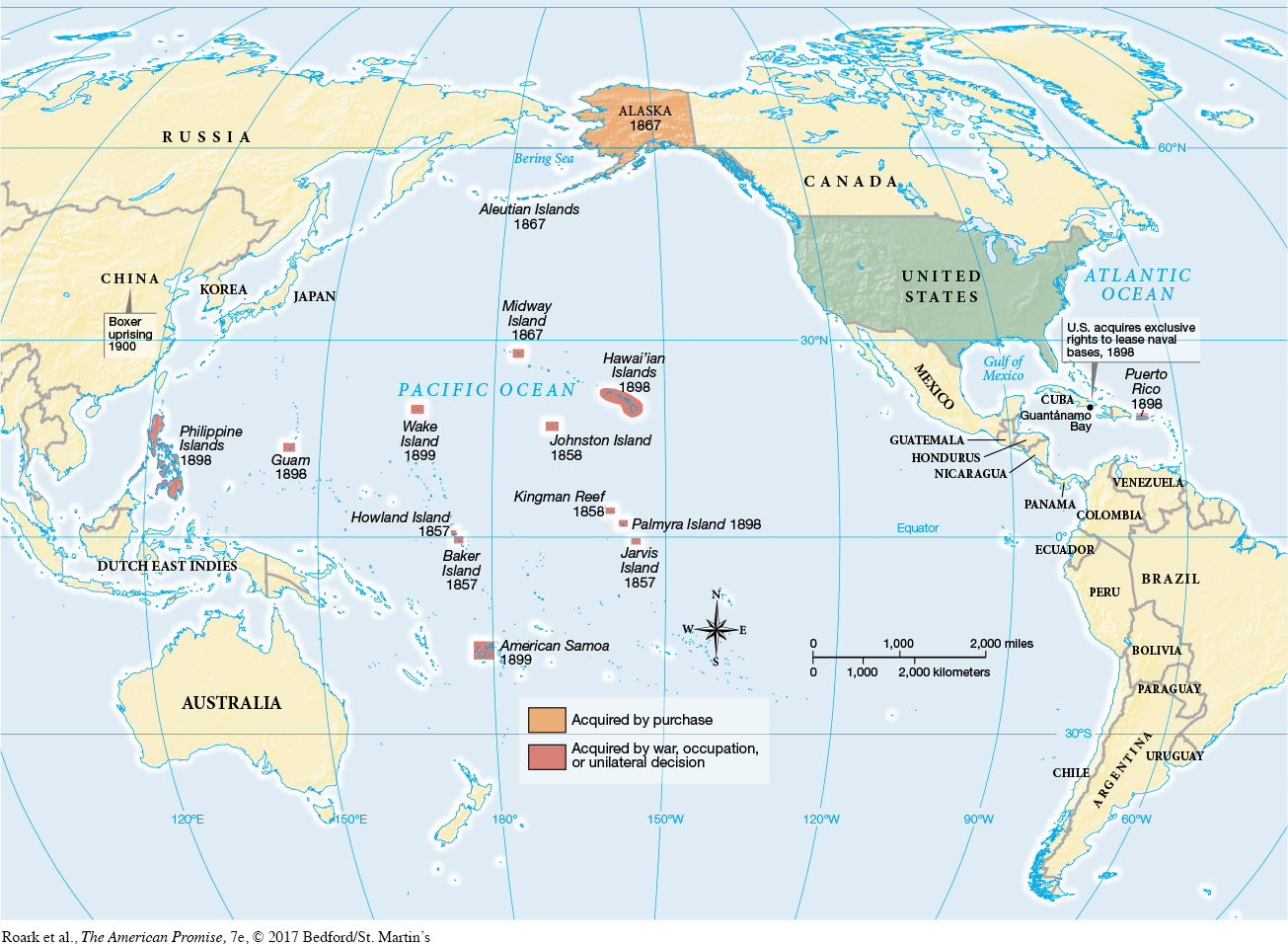

In the formal Treaty of Paris (1898), Spain ceded the Philippines to the United States along with the former Spanish colonies of Puerto Rico and Guam (Map 20.4). Empire did not come cheap. When Spain initially balked at these terms, the United States agreed to pay an indemnity of $20 million for the islands. Nor was the cost measured in money alone. Filipino revolutionaries under Emilio Aguinaldo, who had greeted U.S. troops as liberators, bitterly fought the new masters. It would take seven years and 4,000 American dead—

The American Promise: Printed Page 582

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 531

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 603

Page 583At home, a vocal minority, mostly Democrats and former Populists, resisted the country’s foray into overseas empire, judging it unwise, immoral, and unconstitutional. William Jennings Bryan, who enlisted in the army but never saw action, concluded that American expansionism only distracted the nation from problems at home. Pointing to the central paradox of the war, Representative Bourke Cockran of New York admonished, “We who have been the destroyers of oppression are asked now to become its agents.” But the expansionists won the day. As Senator Knute Nelson of Minnesota assured his colleagues, “We come as ministering angels, not as despots.” Fresh from its conquest of Native Americans in the West, the nation largely embraced the heady mixture of racism and missionary zeal that fueled American adventurism abroad. The Washington Post trumpeted, “The taste of empire is in the mouth of the people,” thrilled at the prospect of “an imperial policy, the Republic renascent, taking her place with the armed nations.”

REVIEWWhy did the United States largely abandon its isolationist foreign policy in the 1890s?